80 Years Later: Remembering Nagasaki As Holy Ground

(ESSAY) At 11:02 a.m. on Aug. 9, 1945, eighty years ago on Saturday, U.S. Army Air Force B-29 Bockscar (sometimes called Bock’s Car) dropped a plutonium-239 bomb called “Fat Man” on Urakami, Japan, the most Christian suburb of the most Christian city in Japan: Nagasaki.

It is the forgotten bomb, the silent bomb. Hiroshima, being the city where the first nuclear bomb, made of uranium and less powerful than the Nagasaki bomb was detonated, is the atomic bombing that all peace movements acclaim: “No more Hiroshimas!”

As a target, Hiroshima made military sense. The city was at the heart of Japan’s war program, Yamamoto’s headquarters, center of military and naval operations. Nagasaki was a secondary target, on the list as an afterthought simply because its production centers were part of the war machine, a minor part, and the city was on the way back for a squadron running low on fuel. This is Nagasaki’s story.

READ: A Look Back In Time To Japan’s Forgotten 19th Century Martyrs

The original target was Kokura, a 100 or so miles to the north. But that city was covered with clouds, 45 minutes had been lost trying to rendezvous with B-29 Big Stink carrying special observers sent by Winston Churchill. In Kokura, fuel was running low. So, Pilot Major Charles Sweeney, 25, also at the helm of one of the planes that had been part of the squadron bombing Hiroshima on Aug. 6, three days before, turned and led his squad of six planes south to Nagasaki.

The target was the city center with its Mitsubishi plant and the Kawanami Shipyard on the nearby harbor. Instead, perhaps feeling the urgency to complete the mission before the fuel ran out, Bockscar’s crew dropped “Fat Man” with its 13-pound plutonium core further north on the suburb of Urakami, less than half a mile from the Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, finished in 1925, blowing it to smithereens.

Coming to confession and to Mass to prepare for the coming Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary the next week on Aug. 15, more people were at the cathedral than on a normal Thursday. In all, 8,500 of the 12,000 Catholics in the area died in the bombing.

Some two miles south, 20-year-old Miyata Kazuma was at home, an injury keeping him away from his job at the Kawanami Shipyard. I met his son Miyata Kazuo a year ago and again this past May in Nagasaki. His dad, Miyata said, spent the next day in Urakami looking for friends, overwhelmed by the suffering and devastation he saw. When we visited the Atom Bomb Museum with Miyata, he pointed to one of the images of a boy with half his face in shreds. When he was a teenager, Miyata said, he had known that boy as an older man. The effects of the bomb lived on in the streets and neighborhoods of Nagasaki for decades.

As Bockscar was leaving a path of destruction, some 100 or so miles to the east Pilot 1st Lt. Earle Craig, Jr., 21, from Beaver, Penn., looked to his left as he led his P-47 Thunderbolts on a bombing mission to the island of Shikoku, the big island just to the south of Hiroshima. Stunned by what he saw, he sent this letter, dated Aug. 9, 1945, home to his parents. The letter is quoted below with permission of his son Earle Craig III:

Actually, I saw one explode, from the distance of 140 miles. I just happened to be looking at the horizon to my left from ‘Cherry's’ cockpit when it seemed as though there was a sunrise at midday. The horizon, even in the brilliant light of near-noon, became a vivid and awful orange. It truly was a horrifying sight.

Then before ten minutes had elapsed, a symmetrical cloud column had risen high into the sky. With our gunsights we estimated the cloud to be 50,000 feet high. It made us feel rather humble, if not futile.

That day, between 40,000 and 75,000 people died, another 60,000 were seriously injured. Over the next five years, more than 100,000 deaths resulted from the bombing. Survivors called hibakusha or “bomb-affected people” were shunned, feared for unknown damage to their bodies that could affect others. Women were afraid to sign up for healthcare as it would make it public that they were survivors, and no one would marry them. Decades later, some children of survivors, like Miyata, felt obliged to tell the parents of people they wanted to marry that history.

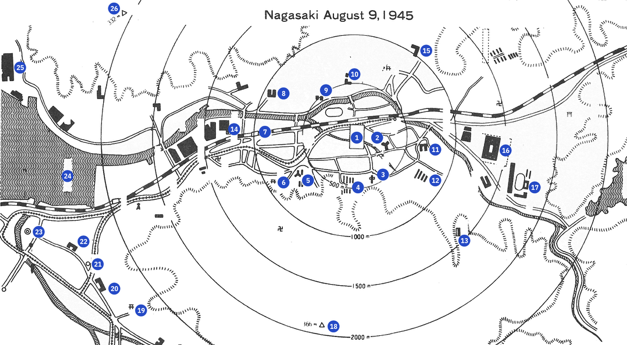

Map of Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945

1 Hypocenter, 2. Nagasaki Prison, 3. Urakami Catholic Church, 4. Nagasaki Medical College, 5. Nagasaki University Hospital, 6. Sannoo Shrine, 7. Urakami Station, 8. Keiho Middle School, 9. Chinzei Gakuin Middle School, 10. Shiroyama Primary School, 11. Yamazato Primary School, 12. Nagasaki Prefectural Technical School, 13. St. Francisco Hospital

14. Mitsubishi Steel Industry, 15. Nagasaki Municipal Cimmetcial School, 16. Mitsubishi Arms Industry, 17. Nishi-Urakami Primary School, 18. Mt. Kompira, 19. Suwa Shirne, 20, Katsuyama Primary School, 21. Nagasaki City Hall, 22. Shinkoozen Primary School, 23. Nagasaki Perfectural Office, 24. Nagasaki Harbor, 25. Mitsubish Dockyard, 26. Mt. Inasad.

On Aug. 15, 1945, the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender and ending the war. The final treaty was signed on board the USS Missouri on Sept. 2, 1945. The bombing of Urakami, Nagasaki, ended the world’s most destructive war.

The significance of the bombing of Urakami and the destruction of the cathedral is rooted in the history of Christianity brought to Japan by Catholic missionaries in the 16th century. One of the ironies of the bombing itself is that, of the 13 crew on board the Bockscar, the pilot and one crew member were practicing Catholics, a third was also a serious Christian. And, according to Sweeney, Chaplain William Downey had “invoked the Lord’s blessing for us and for our flight.”

In his book, “War’s End: An Eyewitness Account of America’s Last Atomic Mission,” Sweeney, an Irish Catholic from Quincy, Mass., wrote the following:

My faith and belief in God were the core of who I was. Since I was a child I had found guidance in the teachings of Jesus and the Church. Jesus taught us to love. He turned the other cheek. Where would he draw the line?

Third Pilot 2nd Lt. Fred Olivi, 22, from Chicago, was the other Catholic. Co-pilot Capt. 1st Lt. Don Albury, 24, from Miami, though not Catholic, was a Christian. In his book, “Nagasaki: The Forgotten Bomb,” Fred W. Chinnock recounted that on the trip back to Okinawa, Albury “prayed to God that what they had just done would help end the fighting and killing.”

Of course, that had been a debate at the highest levels of the U.S. government and military. First, was it necessary to drop an atomic bomb at all? Then, after Hiroshima, was a second strike needed to end the war? President Harry Truman had approved using the bombs – though he was not specifically forewarned about the bombing of Nagasaki.

Gen. Leslie Groves, director of the Manhattan Project, had been the leader of a group of officers who were convinced a second atomic bomb had to be dropped to end the war. He drafted the order for the strikes on July 24, 1945. But it was Col. Paul Tibbets, commander of the 509th Composite Group on Tinian Island, part of Gen. Curtis LeMay’s 21st Bomber Command in the Pacific, who drafted “the top secret order for the first atomic bombing in history” on Aug. 1, 1945, which was sealed and sent by special courier to Gen. Curtis LeMay on Guam. It was Tibbets, who had known Sweeney since 1943, who chose him to pilot the second atomic mission.

Though I had known the basic facts of this history, being the child of a World War II veteran, and had known there was some controversy over whether or not the Nagasaki bomb was necessary to end the war, I didn’t begin to understand what it really meant until our family made a kind of pilgrimage tracing the Christian history of Japan on the island of Kyushu in April 2024 and again in May of this year. Our goal was to understand the history, culture and religion of Japan by visiting important sites and talking with people there.

We began by visiting major Shinto sites in Takachiho Gorge, where we managed to be there on the day of the annual matsuri or celebration of the goddess Amaterasu, legendary ancestor of the emperors of Japan. Then we turned south and west to Shimabara and a very different story.

Roberta Green Ahmanson (center) joined (from left to right) by her son David and husband Howard at Nagasaki Hypocenter Park. (Handout photo)

Christianity is introduced to Japan

That story goes back to the 16th century when Jesuit missionary, now St. Francis Xavier, landed at Kagoshima on Aug. 15, 1549, the same day World War II would end so many centuries later, another irony of this story. He had been in India and stopped at Canton, but in Malacca in 1547 he met a Japanese man named Yajiro who had heard of him and had traveled there to urge him to go to Japan.

Yajiro, who had fled Japan being charged with murder, became the first Japanese Christian. After returning to Goa, Francis Xavier went back to Malacca and Canton, eventually sailing for Japan with Yajiro, two other Japanese men, another priest and a religious brother in 1549. The first port to allow them to land was Kagoshima on the south of Kyushu.

At first, the daimyo (feudal lord) Shimazu Takahisa welcomed them, but within the year he forbade his subjects to convert to Christianity at pain of death. Christians in Kagoshima were not allowed to be given the catechism. Though Portuguese traders had been coming to Japan since 1543, they had not brought missionaries. Francis Xavier had been the first.

Facing the seemingly insurmountable language barrier, Francis Xavier had brought images of the Madonna and the Madonna and Child and used them to tell the Christian story. Realizing that vows of poverty did not appeal to the Japanese, he changed tack and set out in his best vestments with gentlemen and servants all in fine clothes. Hosted by Yajiro’s family until the fall of 1550, he went from there to Yamaguchi on southern Honshu and then eventually to Kyoto where he did not meet the emperor and so returned to Yamaguchi on the southern coast of Honshu in the spring of 1551. There he was allowed to preach.

Next he heard from the Portuguese that Otomo Yoshishige, daimyo of the province of Bungo on north-eastern Kyushu, would like to see him. Francis Xavier set out, again in his best clothes bearing gifts, including a musical instrument and a watch. He was received and allowed to preach. Otomo was one of the first daimyos to become a Christian later in 1578.

Most Japanese were Shinto or Buddhist or a combination of both. Christianity was difficult to accept. Francis Xavier had used the word dainichi, possibly at the suggestion of Yajiro, for the Christian God, but soon learned that the name was confusing because it was the name for the cosmic Buddha Vairocana, the life force that illuminates and pervades all things, a name for a god compatible with Shinto or Buddhism.

Instead, he started using the word deusu for God, drawn from the Latin and Portuguese deus, a term still used by Christians in Japan today. By the time he left Japan in late 1551, missions had been established in Hirado, an island just off Nagasaki that we later visited, Bungo, and Yamaguchi.

There the number of Christians grew. In the next years more missionaries came, mainly from Portugal. In 1563, Christianity reached the Shimabara Peninsula where feudal lord Arima Yoshisada became a Christian in 1576 and gave permission to build a church at Kuchinotsu. Portuguese doctor Luis de Almeida came to the area and Christianity grew rapidly. Churches were built throughout the island and the area became a major Christian center.

I learned that the next chapter of the story when we visited Shimabara, today a nearly two-hour drive from Nagasaki, and its city museum telling the history of Christianity and ultimately its suppression in the area. In 1579, more than 20 years after Francis Xavier had died in China in 1552, Father Alessandro Valignano, 34, son of an Italian aristocrat and a newly-minted Jesuit who had graduated in law at the University of Padua and studied theology in Rome, was appointed Jesuit Visitor of Missions in the Indies: India, China and Japan.

Unlike most Jesuits and all Dominicans and Franciscans, he advocated a policy of “adaptionism,” meaning that instead of trying to convert people to living like European Christians, the missionaries should rather accommodate local customs, customs other Christians found contrary to the values of the faith. Of course, he got into trouble over that. But what is important to this story is that he founded seminaries, one of them in Shimabara. In 1580, an emptied Buddhist monastery in Arima Province was converted into a seminary with 22 young Japanese converts as students. Two years later, another seminary was started at Azuchi. All seminarians received education in Japanese, Latin, the humanities and music.

Valignano advocated learning the local languages, which in China and Japan was not easy, and fought the racism of many European missionaries who saw the Japanese as subnormal and beneath them. So, he required all new missionaries to spend two years in language study and learning Japanese customs. By 1595, the Jesuits had printed a Japanese dictionary and had translated several books, mostly lives of the saints, into Japanese. More important, Valignano insisted the Japanese who joined the Jesuit Order were to be treated as equals to the Europeans.

All of this cost money, of course, and that caused another problem. In 1563, Omura Sumitada, the daimyo in control of Nagasaki, was baptized and in by 1580 gave the port of Nagasaki, then a small fishing village, to the Jesuits. Fees from the port supported the mission. This, of course, caused its own difficulties. The Jesuit Superior General back in Rome was shocked by all this and gave instructions the arrangement should only be temporary. But Valignano and the other Jesuits ignored him. Then, as persecution rose after 1587, the town became a haven for Christians.

In 1582, Valignano convinced three daimyos, among them Otomo Sorin of Bungo Province and Arima Harunobu, son of Yoshisada, of Shimabara, to sponsor four young Japanese noblemen and graduates of the seminary to travel to Europe. The four were Mancio Ito, their leader, and Miguel Chijiwa as representatives of the daimyos and Julião Nakaura and Martinho Hara as their companions. They left on Feb. 20, 1582. Valignano accompanied them as far as Goa. Diogo de Mesquita went along as tutor, mentor and interpreter.

After nine months visiting Portuguese outposts in China, India and Madagascar, they went on to land in Lisbon in August 1584, eventually going on to Madrid, where they met King Philip II, then Toledo, and then to Rome where they met both Popes Gregory XIII and Sixtus V. The Roman Senate made the boys citizens and patricians of Rome. They amazed those they met with their skills. This was at the same time that indigenous peoples were being enslaved and killed in the Americas, believed by some to be subhuman. Clearly, these Japanese were equal to the Europeans, perhaps a point Valignano had wanted to make.

A icon of St. Paul Miki. (Photo via CatholictotheMax.com)

Growing persecution against Christians

The group returned to Japan in 1590 to find Christians facing danger. Seeing Christianity as a threat both to the nation and to Buddhism, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the first leader to have total control of Japan, had issued an order to expel all Christian missionaries in 1587, though he didn’t enforce it rigorously at first. Then, in 1596, a Spanish ship washed up on Shikoku, the crew was spared, but the cargo was confiscated. The incident made Hideyoshi increasingly suspicious of the Spanish and therefore of Christians, Franciscan missionaries in particular.

The following year in Kyoto, Hideyoshi rounded up 24 Christian men in order to force them to march at sword point the 400 miles to Nagasaki, there to be publicly crucified on a hill above the harbor as a warning to all Japanese not to embrace the Christian faith. Six were Franciscan missionaries, four from Spain and one each from Portugal and Mexico. The Mexican was St. Philip (Felipe) of Jesus from Cuernavaca, Mexico. He had been on a Spanish galleon that washed up on the southern shore of Shikoku. Arrested there, he was sent to Kyoto, where he joined the group.

Later, Mexican researchers discovered Felipe may not have been as heroic as he has been made out to be. Whatever the case, he died with the others. Three were Japanese Jesuits, among them St. Paul Miki, son of a Christian samurai. The rest of the group were 15 members of the Third Order Franciscans, three of those altar boys, ages 12, 13 and 14. Sts. Francis and Peter Sukejiro started out from Kyoto only to help, but along the way they joined the group, bringing the number to 26. All were beatified in 1627 and canonized by Pope Pius IX in 1862.

From the cross, St. Paul Miki said: “The Christian law commands that we forgive our enemies and those who have wronged us. I must therefore say here that I forgive Taikosama (Hideyoshi). I would rather have all the Japanese become Christians.”

The 26 Martyrs Museum and St. Felipe Catholic Church, named for that Mexican Franciscan, stand on the hill where the 26 were crucified and lanced. A Jesuit priest, Renzo De Luca, is its director and Miyata Kazuo works as manager.

In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu founded the shogunate that ruled Japan from then until 1868. In 1614, he officially outlawed Christianity. Persecutions stepped up throughout Shimabara and Nagasaki. Some of that story can now be seen in the new multi-Emmy Award-nominated video version of James Clavell’s best-selling book, “Shogun” featuring Japanese and English-speaking actors.

Of the four young ambassadors to Europe, Ito died in Nagasaki in 1612. Hara was banished in 1614 and went to Macau, where he died in 1629. Chijiwa was the only one to leave the Jesuits and was believed to have renounced his faith, but a rosary found in his grave suggests that might not be so. In hiding after 1614, Nakaura was captured by the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1633. He died a martyr, by torture, on October 21of that year. He was beatified in 2008. The 26 Martyrs Museum has a hand-written letter Nakaura sent to Jesuit priest Nuno Mascarenhas in Rome dated 1621. He writes of friends telling him to move as a new persecution had started. He closed by saying: “We are confident that our Lord will give us perseverance and courage.”

In those years, persecutions were sporadic, but lethal. Scholars disagree, but the best estimate is that between 2,000 and 5,000 Christians were killed between 1614 and 1873, other than those killed at Hara Castle. Some put the number much higher. In Unzen, up in the Shimabara Peninsula mountains, we stayed in a brand new hotel that faced a hillside covered with sulfur hot springs. Japan is volcanic. Hot springs are everywhere. The hotel garden connected to a walking path up the hillside and around the springs. As we walked, we found plaques noting the Christian martyrs who had been boiled to death there, with names and dates.

Just 15 miles away, outside Shimabara, we visited the site of the largest single massacre of Christians and others in the period. As we learned on our visit to the museum there, this was the domain where Arima Yoshisada had given permission to build the first church in the area in 1563. His son, Arima Harunobu, had been removed with the 1614 ban on Christianity, and the Matsukura clan who were not Christians were put into power.

In 1637, in a time of famine, daimyo Matsukura Katsuie raised taxes to build a new castle and mercilessly persecuted Christian peasants who were most of the population who worked the land. The area was also home to many ronin, samurai who were no longer connected to a daimyo and were rootless, sometimes bandits. Outraged and hungry, the two groups became allies and rebelled. Katsuie persuaded the Tokugawa to send forces from surrounding and distant domains, the exact numbers ranging from 100,000 to as many as 200,000 men.

The rebels elected the 16-year-old Christian Amakusa Shiro (his manifesto can be seen today in the museum in the castle Katsuie built.) as their leader. Ultimately, they holed up in Hara Castle which had been built by the Arima. From December 1637 to April 1638, the rebels resisted the siege. But on April 12, the Shogunate’s forces stormed the castle, only taking the final holdouts on April 15, 1638. Some 37,000 men, women and children – all but 1,000 or so of them Christians – were beheaded, their bodies left lying on the ground for 100 years.

Amakusa’s severed head was one of more than 3,000 taken to Nagasaki and may have been one of those publicly displayed at Dejima, the island created for foreign traders. A brutal ruler, Katsuie was first pressured to commit seppuku or ritual suicide, but when the body of a murdered peasant was found in his residence, he was beheaded in Edo. In Shimabara, because most men who worked the rice fields had been killed at Hara Castle, immigrants had to be sent in from all over Japan to resettle the land. Towns in the area to this day have a varied mix of dialects due to the mass immigration. And all inhabitants were required to register with local Buddhist temples. Today, a Japanese manga called “Amakusa 1637” tells the story. So far it has been translated only into French.

We visited on a clear, sun-shiny day, the only people there. Quiet, the quiet of the dead. The land has never been built on. Our local guide told us that Japanese people don’t go there; they think it’s haunted. And, indeed it felt that way. There is no real monument to the Shimabara Rebellion, though a sign tells the story. Off in some trees is a statue of Amakusa Shiro. Then, beyond more trees there are three smaller, old-looking stone statues that are Amakusa, his mother or maybe his sister, and Francis Xavier. Our guide said no one knows who put them there.

For the next 200 years, Japan was closed to the West, only the Dutch were allowed to trade from the man-made island of Dejima in Nagasaki harbor. In Nagasaki and the surrounding region, anyone suspected of being a Christian was called to the Tokugawa headman’s headquarters and forced to stomp on a flat iron image of either the Crucifixion or the Madonna holding the Christ Child, called the Fumi-e, or face death. That building was on a hill in Urakami.

In 1852, American veteran of both the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War Commodore Matthew C. Perry was assigned by American President Millard Fillmore to force Japan to open its ports to Western trade, at gunpoint only if absolutely necessary. With two steamships and two sailing sloops, Perry sailed into Edo Bay, now Tokyo Bay, on Feb. 13, 1853.

Never reaching Edo, now Tokyo, he pointed his guns at the town of Uraga at the entrance to the bay. Shogun Tokugawa Ieyoshi was ill and incapacitated. The Council of Elders, closest advisers to the shogun, dithered. Finally, on July 11 Roju (one of the Council of Elders) Abe Masahiro accepted a letter from Perry and allowed him to land at Kurihama on July 14. Perry left saying he would return within the year.

On Feb. 13, 1854 he did, with 10 ships and 1,600 men. He was permitted to land at Kanagawa, now part of Yokohama, and on March 31 the Treaty of Kanagawa was signed by Perry and an imperial official Daigoku-no-kami Hayashi Akira. More trade treaties followed – an 1855 treaty with Russia, then in 1859 the Ansei Treaties and the Harris Treaty, which had been signed in 1858, with the United States went into effect. It was the treaty with Russia that designated Nagasaki an open port and granted extraterritoriality privileges to foreigners in Japan.

In 1860, Nagasaki developed the area around Oura Creek on the hills above the harbor and ordered foreigners to live there. In 1862 two French priests of the Société des Missions Étrangères de Paris, Fathers Louis Furet and Bernard Petitjean, were sent to Nagasaki to build a church in honor of the 26 Martyrs. They arrived in 1863 and a small wooden church was opened in 1865. In 1879, it was totally remodeled into a five-aisled church made of stuccoed brick, the building you see today.

A view of modern-day Nagasaki. (Wikipedia Commons photo)

‘Where is the statue of the Holy Mary?’

The church was only for foreigners. Christianity was still illegal for Japanese citizens. But, on March 17, 1865, Petitjean noticed a group of Japanese people out front. One old woman among them spoke to the father: “The heart of all of us is the same as yours. Where is the statue of the Holy Mary?”

Japanese Christians had been forced underground for 250 years, worshiping in secret. Many, but not all, had moved to the islands off Nagasaki. They became known as Kakure Kirishitans (hidden Christians). We visited a museum on Hirado, the island closest to Nagasaki, that told their story. On a bright sunny day, Miyata Kazuo took us to Oura Church high on a hill near Glover Park. His own father had come from a hidden Christian family on the Goto islands to the south, something his grandmother had told her son never to mention.

Halfway up the stairs to the entrance of the church is a small park with a relief of the hidden Christians meeting Petitjean and a statue of Pope John Paul II who visited. Inside you can still see the statue of the Virgin Mary those first hidden Christians saw that day. Petitjean quickly learned that almost all the people in Urakami were Christians. Damaged but not destroyed on Aug. 9, 1945, Oura Church was the first Western building declared a National Treasure by Japan.

Though foreigners were allowed to build Christian churches, they were confined to the foreign district. Christianity was still illegal for citizens of Japan. A new persecution ensued after the Meiji Restoration in 1868 ended the Tokugawa Shogunate’s 250-year rule. On June 7, 1868, more than 4,000 Christians in Urakami were ordered to be deported. Between then and 1870 some 3,400 Christians were rounded up and sent into exile from Urakami and the Nagasaki area.

In 1869, 153 of them were sent to Tsuwano on Honshu, another place we visited. When they would not renounce their faith, they were put in cages in winter with only a loincloth to wear. One of them claimed the Virgin Mary appeared to comfort him for eight nights in a row. He and thirty-six others died. We followed the pilgrim route from Tsuwano Catholic Church up the hillside to the site where a sculpture of the Virgin Mary faces that of a caged man. A chapel stands nearby. It’s an idyllic spot, surrounded by firs and pines. Though we were there in April, the spring chill was a reminder of what winter must have been like. A total of 650 Christians were martyred before, under pressure from the West, the Meiji Government granted religious freedom in its new constitution in 1873.

Now free, the returning Urakami Christians wanted to build a cathedral. They bought the land where the former Tokugawa headman had forced their ancestors to stomp on the Fumi-e every New Year to prove they were not Christians. In 1875, French priest and missionary named Pierre-Théodore Fraineau, a stone mason and architect who arrived in Nagasaki in 1873, was placed in charge of the project to build Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception Cathedral, known both as St. Mary’s and Urakami Cathedral. He completed the design in 1881, collected funds, and started construction in 1895. He carved many of the statues, most destroyed in 1945, and stone masons from Amakusa Island did much of the work. When Fraineau died in 1911, Father Émile Raguet took over. Construction was largely complete in 1914 – but it was not dedicated until the bell towers with bells installed were complete in 1925.

Meanwhile, two other people important to the story had come to Urakami. Nagai Takashi was born in 1908 in Matsue in northwestern Honshu, his father trained in Western Medicine, his mother a descendant of an old family of samurai. Boarding with cousins, he attended high school in Matsue, interested in atheism and curious about Christianity. In 1928 he entered Nagasaki Medical College and joined a poetry club and the basketball team. His mother’s death in 1930 from a brain hemorrhage led him to the works of Blaise Pascal, particularly the “Pensées.”

He boarded with the Moriyama family, for seven generations leaders of a group of Kakure Kirishitans. From them he learned that the construction of the cathedral was funded by poor farmers and fishermen, descendants of those hidden Christians.

In 1932 celebrating at a party the night before his graduation he got drunk and spent a night outside, getting drenched with rain, and contracted a form of meningitis which left him with impaired hearing, making it no longer possible to use a stethoscope properly. Consequently, he turned to radiology research. In 1932 Moriyama Sadakichi’s daughter Midori came down with acute appendicitis. Nagai carried her on his back through the snow to the hospital where immediate surgery saved her life. The pair were married in 1934, also the year that Nagai was baptized and confirmed in the Catholic Church.

Nagai started working with the Society of St. Vincent de Paul, helping the poor in the area. Through that he met a priest named Maximilian Kolbe who had started a Franciscan church and monastery in Urakami in 1931, the church and monastery along with a school built later continue to operate today. We visited in 2024. Kolbe had come as a missionary to start the work and publish Christian materials in Japanese. He was made guardian of the monastery he had started in Poland in 1936 and returned there full time in that year. Eventually, he was arrested by the Gestapo and in 1941 sent to Auschwitz where at the end of July he traded his life for a fellow prisoner who had a wife and children. He died on Aug. 14. Saint Pope John Paul II canonized him in 1982.

Nagai served as a medic for the Japanese in Manchuria in 1933 and again from 1937 to 1940. When he returned, disturbed by the way the Japanese military treated local people, he resumed his studies and radiology research, receiving a doctorate in 1944. Complaining of pain since 1940, Nagai was diagnosed with leukemia in June 1945, no doubt due to his exposure to radiation. When he and Midori heard about the bombing on Aug. 6, they took their two surviving children, one daughter had died at birth and another as a small child, and Midori’s mother to Matsuyama in the country. Back in the city Nagai continued working at the hospital treating the injured from an April 26 air raid on Nagasaki.

On Aug. 9, Nagai was at the hospital, Midori at their home. Injured, his right temporal artery severed, Nagai kept helping the wounded. On Aug. 11 he went home to find his house in ruins, Midori dead. We saw her rosary in the Atom Bomb Museum. In bed for a month with his head wound and atom bomb sickness, Nagai drank water from Lourdes that had been at the monastery started by Kolbe and asked Kolbe to intercede for him.

Soon after the war, Nagai built a hut for his family out of the ruins of his home, then in 1948 the St. Vincent de Paul Society approached the local parish priest to organize church members and the Catholic Carpenters Association to build him a small structure that we visited last year. Next door is a Museum run today by his grandson Nagai Tokusaburo, whom we met on that same visit. From July 1946, when he was no longer able to teach, until his death in 1951 Nagai wrote a number of books including the best-selling “Bells of Nagasaki,” completed in 1946 not long after his collapse.

A Catholic Church in Nagasaki destroyed by the Aug. 9, 1945, atomic bombing of the city. (Wikimedia Commons photo)

‘Why did God allow the bomb to be dropped there?’

The bombing of Urakami and destruction of the original cathedral posed a deep question for the surviving Christians. Given their history, why did God allow the bomb to be dropped there? Why were they called to suffer yet again? Nagai believed that God had chosen the Urakami Catholics who died to be a sacrifice of atonement for the sin of the war, chosen to end the fighting. He referred to it as a “great holocaust” and urged his Catholic brothers and sisters to look to Christ who suffered on the cross on Calvary, in the cross they could find meaning for their own suffering.

Some Christians found consolation in his thinking, Miyata told us. Others did not. Whether that second bomb was necessary to end the war is still a question today. Our Japanese friends shake their heads. Yes, they say reluctantly. The army had stated repeatedly they would fight to the last man. And, Hiroshima hadn’t ended the war.

Last year, we visited the Hypocenter, the place where “Fat Man” was detonated. At the center is a memorial. Off to one side are pieces of the cathedral. On another side are Buddhist lanterns, remnants of a Buddhist temple that was also destroyed, whose leaders had registered hidden Christians, knowing they were Christians, to protect them from the authorities. It is another silent place, no one there but us. A surprisingly short walk took us to the cathedral.

After the war ended on Aug. 15, 1945, the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, when the emperor conceded defeat, there was determination to rebuild the destroyed cathedral. But where? Some wanted to make a memorial of the ruins and build elsewhere. Others wanted to reclaim the original site with its layers of meaning, having been built on the ground where so many Christians had been humiliated over the centuries. Some thought the Americans wanted it rebuilt on the same site to cover their shame for having destroyed a Christian cathedral. In the end, Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception rose again on the site where she had originally been built. The church was completed in 1959 and remodeled in 1980 using brick to resemble the original French style of the former building.

On the grounds there is a memorial to a man born in 1873 who died in 1922, his forebears having survived the 1869 persecution. There are also the damaged statues of the Virgin Mary and Jesus. Other pieces from the ruins are in the park at the Hypocenter and the Atom Bomb Museum.

The towers of the original cathedral had each held one bronze bell. The larger one almost miraculously survived the bombing and was put back in its place when the new cathedral was built. The other tower remained silent, its bell a victim of the bomb. In 2023, James Nolan Jr., professor of sociology at Williams College in Massachusetts and grandson of the staff doctor at Los Alamos for the Manhattan project, went to Urakami. There, according to Japanese newspaper “The Mainichi,” he met Moriuchi Kojiro, a local Catholic and descendant of hidden Christians as well as a second-generation hibakusha. Moriuchi suggested it would be wonderful if Americans donated a new bell like the smaller one that had been destroyed.

Nolan went home, gave talks and raised the money from some 500 Catholics for a total of $105,000. On Aug. 9, 2025, on the 80th anniversary of the bombing, two bells will once again ring from the towers of Urakami Cathedral, one for the first time.

We don’t know what Secretary of War Henry Stimson or Groves or LeMay or Tibbets knew about Nagasaki and its history, let alone what Sweeney and the other 12 members of the crew of Bockscar knew as they flew on that Thursday in 1945. In fact, J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II, hadn’t even included Nagasaki on the original target list. It was added later as a possibility.

Perhaps little did any of them know that the bomb was dropped into a centuries-long history of Christian faith, struggle and survival. It is both a surprising and, in some ways, unfinished story. There are only 600,000 Catholics in all of Japan today, a country of 124.5 million people, with only ten seminarians studying for the priesthood in Tokyo.

On our visits in 2024 and 2025 we traveled through layer upon layer of history across the mountains of Kyushu to Urakami and Nagasaki. Then, on a Saturday evening this past May, we sat with our friends and a Norbertine father traveling with us in that rebuilt cathedral, packed with the faithful, listening to the descendants of those struggles singing as they celebrated vespers Mass. For some reason, I felt hot tears. In Urakami, Nagasaki, the faithful are still there.

Roberta Ahmanson is a philanthropist, art collector and writer who started her career as a religion reporter at the San Bernadino Sun and Orange County Register. She is the co-author of “Islam at the Crossroads” and “Blind Spot: When Journalists Don’t Get Religion.” She is also the chairperson of The Media Project’s Board of Directors.