Faith Meets The Future: Religion And The Gene Editing Divide

(ANALYSIS) The number of advancements occurring in the medical community every year are astounding. For instance, there’s now an incredibly effective treatment for cystic fibrosis and hepatitis C.

For people with cancers that are responsive to immunotherapy, there have been incredibly promising drug trials. In one trial of 103 people, reported in the New York Times, just five had a recurrence of cancer within five years.

And more and more Americans are taking GLP-1 medications that lead to significant and sustained weight loss. More recent studies have found that those taking the drugs are also seeing a reduction in smoking and alcohol consumption.

But among all the things just listed, it’s hard to really pinpoint an ethical concern. Many of these drugs just do what pharmaceuticals have been doing for decades — reducing illness and treating disease. None of these therapies make any permanent changes to the human body.

However, the next wave of treatments may wade into murky philosophical and religious territory. Just a few weeks ago, the New York Times ran a stunning headline, “Baby Is Healed With World’s First Personalized Gene-Editing Treatment.”

The child was born with an incredibly rare genetic disorder that would almost certainly end his life at a very young age. Doctors sprang into action and developed a highly personalized gene editing treatment for the baby’s genetic abnormality. The treatment worked, and his team of doctors and nurses is preparing for the patient to go home — an outcome that was medically impossible just a few years ago.

This is the first case of successful gene editing that’s ever been reported, and it certainly won’t be the last. But the religious response to gene editing is decidedly mixed. Some evangelical organizations have likened some versions of the process to “playing God.”

While others, like the Vatican, have taken a more nuanced position on the topic — saying that therapeutic gene editing should be permitted as long as the scientific process doesn’t include the destruction of embryos.

Back in 2021, the Pew Research Center fielded a survey that included a battery of questions about gene editing practices and implications. That data is hosted on the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). There’s a lot to learn here about what factors shape people’s views of the technique and how much (or how little) religious concerns play a role.

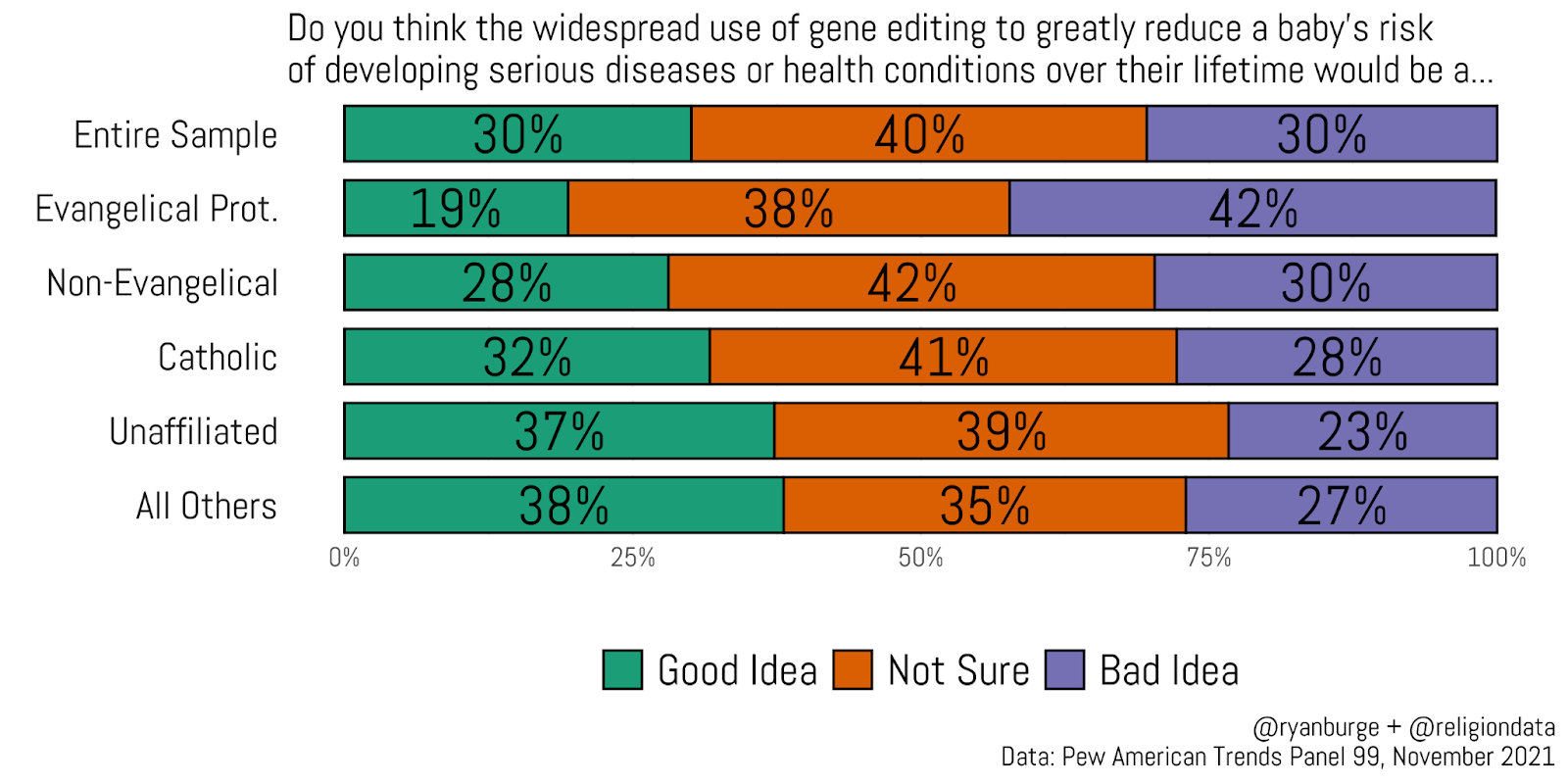

The questionnaire asks respondents, “Do you think the widespread use of gene editing to greatly reduce a baby’s risk of developing serious diseases or health conditions over their lifetime would be a …”

In the entire sample, I think the best description of the results is ambivalence. About 30% of the public thinks this is a good idea, and the exact same share thinks it’s a bad idea. The plurality response was “not sure” at 40% of the general public. That’s a pretty good indication to me that the average person is not spending a whole lot of time thinking about the implications of gene editing.

To read the rest of Ryan Burge’s post, visit his Substack page.

Ryan Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University, a pastor in the American Baptist Church and the co-founder and frequent contributor to Religion in Public, a forum for scholars of religion and politics to make their work accessible to a more general audience. His research focuses on the intersection of religiosity and political behavior, especially in the U.S. Follow him on X at @ryanburge.