Are The Most Educated Really The Least Religious?

(ANALYSIS) One of the biggest limitations of the kind of work I do is that it’s often at the aggregate level. In layman’s terms, that’s when I use every respondent in a survey sample.

So when I say things like “older people tend to be more religious than younger people” or “women tend to be more likely to go to church than men” — that’s a statement based on analysis where no one is filtered out.

But the underlying statistical reality is that I am talking predominantly about white respondents. The reason for this is simple - most American adults are white. In the 2024 Cooperative Election Study, it’s about 68% of all respondents. So aggregate level analysis may be obfuscating the fact that some relationships that appear at the top level don’t persist when the data is limited to just African-Americans or Asian-Americans.

Let me show you a graph that really kicked off this entire analysis - it’s one that I’ve written about quite a bit on this newsletter.

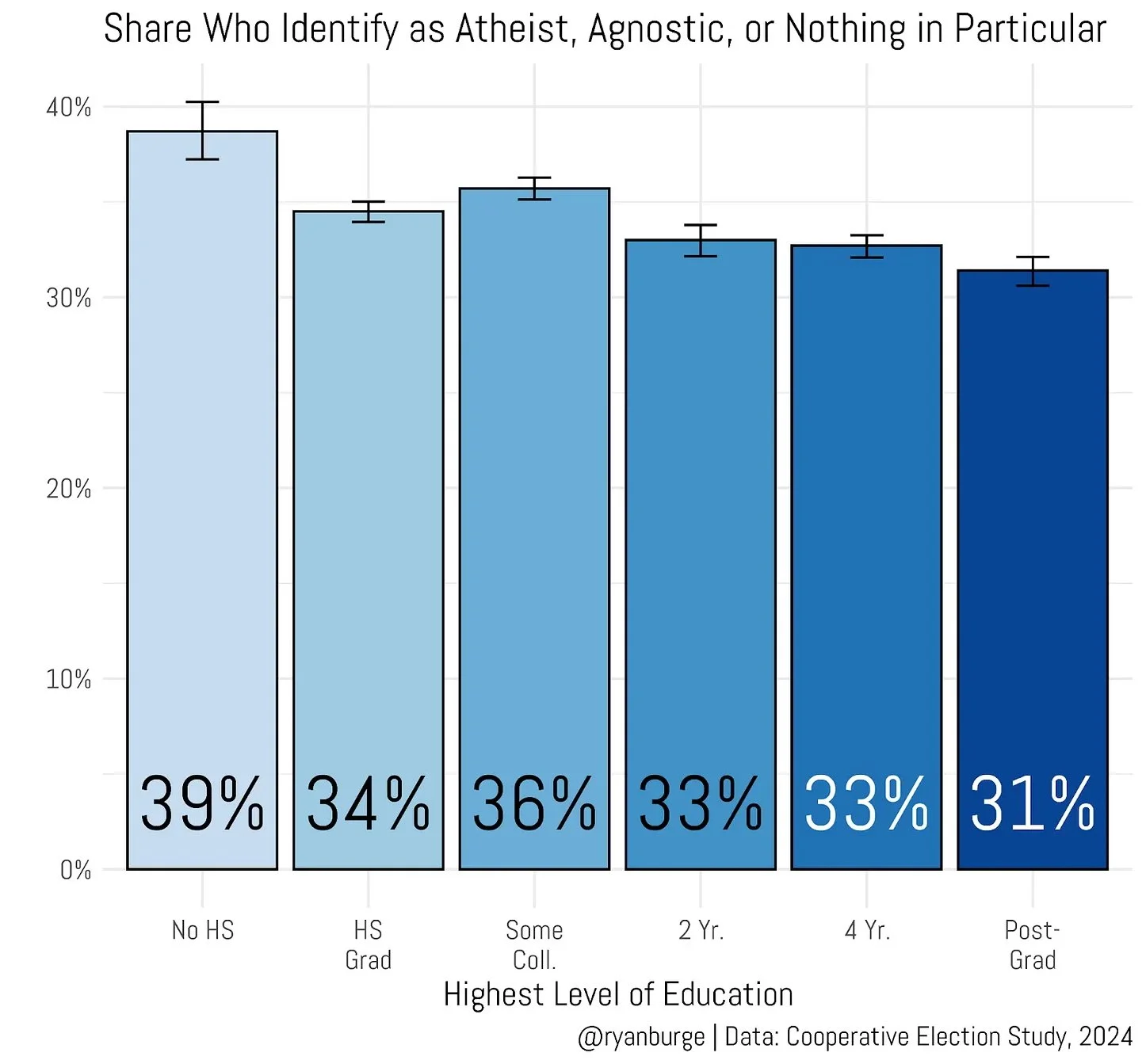

It’s really, really simple. It’s the share of people who identify as atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular (the nones) by level of educational attainment. Whenever I post it on social media, it always causes quite a stir.

The interpretation is pretty simple, really. Folks who didn’t finish high school are the most likely to identify as non-religious (39%). Among those who went a bit further in their education, about 35% are atheists, agnostics, or nothing in particular.

For those who finished a four-year degree, one third are non-religious and it drops even lower for those who have taken coursework at the graduate level — just 31% are nones.

The upshot of this is simple and counterintuitive for many: there’s no empirical evidence that educated people are more likely to flee religious affiliation. Actually, there’s a slight negative relationship in this data. Those with the most education are the least likely to identify as atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular.

But remember - this data is at the top level. So maybe what’s happening is that this overall relationship is negative for white people but it may be positive for Black, Hispanic, or Asian respondents. I just wanted to explore that possibility in the rest of the post today.

You can read the rest of Ryan Burge’s post at his Substack channel.

Ryan Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University, a pastor in the American Baptist Church and the co-founder and frequent contributor to Religion in Public, a forum for scholars of religion and politics to make their work accessible to a more general audience. His research focuses on the intersection of religiosity and political behavior, especially in the U.S. Follow him on X at @ryanburge.