‘Reading The Church Fathers’ Tells The Story Of How The Past Shaped The Church We Know Today

(REVIEW) The faith Christians practice today has a long and enduring history. It is often something many either ignore or don’t think too much about.

Emerging from a small sect within Judaism, early Christianity absorbed much of the religious, cultural and philosophical traditions of the Greco-Roman world at the time. The decades and centuries that followed the crucifixion of Jesus were ones of intense persecution, but Christianity would eventually flourish and become the state religion of the Roman Empire.

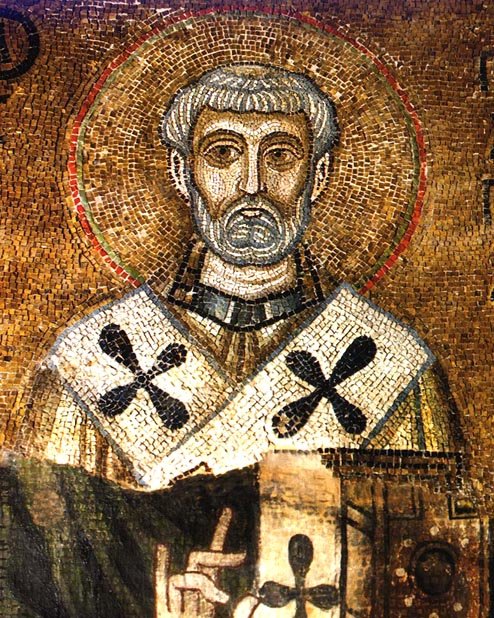

Clemente I, one of the church fathers featured in a new book, as depicted in a mosaic from St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, Ukraine. Wikipedia Commons photo

Heresies and persecutions stirred up the passions of early Christians, who lived within the larger Roman Empire, against those in political power at the time. The tensions the followers of Jesus suffered also included those within Judaism — a majority of whom in that period followed the Pharisees — culminating with the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem by the Romans in A.D. 70.

READ: Delving Into The Life Of Mary Magdalene And Debunking Centuries-Old Myths

In his new book, “Reading the Church Fathers: A History of the Early Church and the Development of Doctrine” (Sophia Institute Press), author James Papandrea musters all his historical might to produce a 464-page tome infused with theology, outlining the principles and teachings that guided early Christianity from the time of the New Testament writings to the development of doctrines.

This book is a must for history buffs with an interest in religion. It is not necessarily a summer read, so this may not be the best book to lug to the pool. Instead, it’s a great way to take a trip back in time — preferably from the comforts of your living room — to when Christians suffered persecution at the hands of the Romans.

“Once Christianity was under the umbrella of Judaism,” Papandrea notes, “it became perceived as something new, and therefore potentially dangerous.”

At the same time as Christian beliefs were evolving, this new faith, Papandrea writes, “inherited some of the cultural aspects of Greek philosophy.”

Papandrea sets forth the thesis that Christianity was a marriage between Hebrew thought and Greco-Roman philosophy, arguing that the early church fathers “assumed that revelation and philosophy were not necessarily at odds” and that “human reason could be guided by God.”

With that, Papandrea is off to the races, and this brick of a book becomes something of a page-turner somewhere in the middle of Chapter 2, after all the basics are laid out for all types of readers to be able to understand the context with which future events can be discerned.

One early Christian Papandrea writes about is Clement of Rome, also known as Pope Clement I. He is considered to be the first Apostolic Father of the church — one of the three chief ones, together with Polycarp and Ignatius of Antioch, who served as pope between A.D. 88 and 99.

Interestingly, Clement’s view on justification has been the focus of scholarly debate given that he sometimes argued to have believed “sola fide” — justification by faith alone. The debate persists because Clement directly stated that “we are not justified by ourselves but by faith” but also stressed judgment on sin. The Protestant scholar Tom Schreiner has argued that Clement of Rome believed in a grace-oriented justification by faith, which will cause the believer to do works as a result.

Papandrea doesn’t get into any of this, but he does mention St. Clement’s Basilica, located a short walk from the Colosseum in Rome. It is a house of worship easily overlooked by tourists but well worth a trip. Papandrea writes that this site is where Clement presided and that it’s “truly holy ground to stand in a place where Christian worship has been conducted continuously for over 1,900 years.”

“Reading the Church Fathers” traces the development of doctrine through the late 1100s, covering nearly 1,000 years of Christianity. Throughout that journey, Papandrea profiles notable church fathers, but a turning point for the book — and indeed Christianity — takes place in Chapter 10. It was in the fourth century that Emperor Diocletian embarked on what’s known as the Great Persecution. Interestingly, a general at that time, a man known as Constantine, became the first Christian emperor.

It was in the year 313 that the Edict of Milan legalized Christianity throughout the Roman empire. Constantine ordered that churches could own property and reparations owed to them for past persecution. Clergy were exempted from taxes, and Christianity replaced pagan symbols.

“Constantine never rules as a baptized Christian,” Papandrea notes. “Like many men at his time, Constantine postponed baptism until the end of his life, in part so that he would not be held to the moral standards of the church.”

It’s this type of meticulous research — while also addressing and trying to debunk myths — that makes this book so interesting. The use of maps and extensive footnotes allows for even greater context in the broad debates that helped define Christianity throughout those early centuries. There are lots of books out there about the early church, but “Reading the Church Fathers” is an exhaustive volume that’s worth your time — when you’re not at the beach or pool.

Clemente Lisi is a senior editor and regular contributor to Religion Unplugged. He is the former deputy head of news at the New York Daily News and teaches journalism at The King’s College in New York City. Follow him on Twitter @ClementeLisi.