This Indonesian village tradition has kept peace between Christians and Muslims

Christian villagers from Passo and Muslim villagers from Batumerah celebrate religious festivals together. Photo courtesy of the chief of Batumerah.

(COMMENTARY) Peaceful, and even loving religious co-existence, does not require secularism or relativism, nor a belief that our differing beliefs do not matter. It requires us to respect one another even with our differences. This civic comfort with differences may be itself religiously-based, something much needed in our increasingly religious world. One example of religiously-based respect is shown in the “pela” relations in the towns in Indonesia’s Maluku islands.

The king of Batumerah village in Maluku in his official dress. Photo by Matius Ho.

In a beautiful country, the islands in East Indonesia are especially beautiful. The islands in Maluku were long known as the “spice islands” and were a source of great wealth and international power to whoever could control them.

This led to conflict between the British and Dutch colonialists and, eventually, the Dutch managed to control most of the islands, but not the island of Run. Considering it a vital interest to remove this British outpost from their midst, they agreed in the 1674 Treaty of Westminster to give the British a different island in exchange for Run: that island was Manhattan.

In 1998, with the end of Suharto’s 31-year authoritarian rule, Indonesia erupted in violence. The largest death toll was in these eastern islands from 1999 to 2002. Tensions between Christians and Muslims, each about 50 percent of the population, led to sectarian violence, and then the intervention of thousands of well-armed members of the radical militia Laskar Jihad from Java led to massacres of the Christian population. Almost 5,000 people were killed and a third of the population of Maluku and North Maluku were displaced.[i]

Dr. Abidin Wakano, a lecturer at the State Institute for Islamic Studies in Maluku’s capital, Ambon, also runs an excellent Center for Mediation and Reconciliation.[ii] In looking back on the conflict and its aftermath, he lamented that the past trauma of the islands, and the subsequent division of the population, often prevents even young Indonesians from experiencing a full recovery.

“Children, teachers, educators, and religious leaders have grown up inheriting stories from the past,” Wakano said. “I am pretty sure some people still keep weapons. Our lives are segregated…. Muslims live on their own. Christians live on their own. It is okay that we can't live together anymore. But at least, there should be programs to facilitate youth meetings. Our generation has the experience of living together, but not the young generation.”

Consequently, the center has an extensive range of educational and training programs, including a live-in program where Muslim teachers stay in Christian villages and vice versa. Muslim grade school students take Christmas gifts to Christian schools, and Christian kids reciprocate at the feasts ending the Ramadan fast.

Religious leaders from both sides have also been working to restore their relations and communities. The Chairman of the Indonesian Ulama Council in Ambon said he believed that the situation had improved significantly, but it had not yet returned to the many harmonious relationships existing prior to the conflict.

Maluku has managed to dampen religious conflict and has made some steps in repairing relations because of its traditions, like “pela” covenants—formal relations of peace and friendship between many of the villages in the archipelago. One example is the covenant between the villages of Passo, now Christian, and Batumerah, now Muslim.[iii]

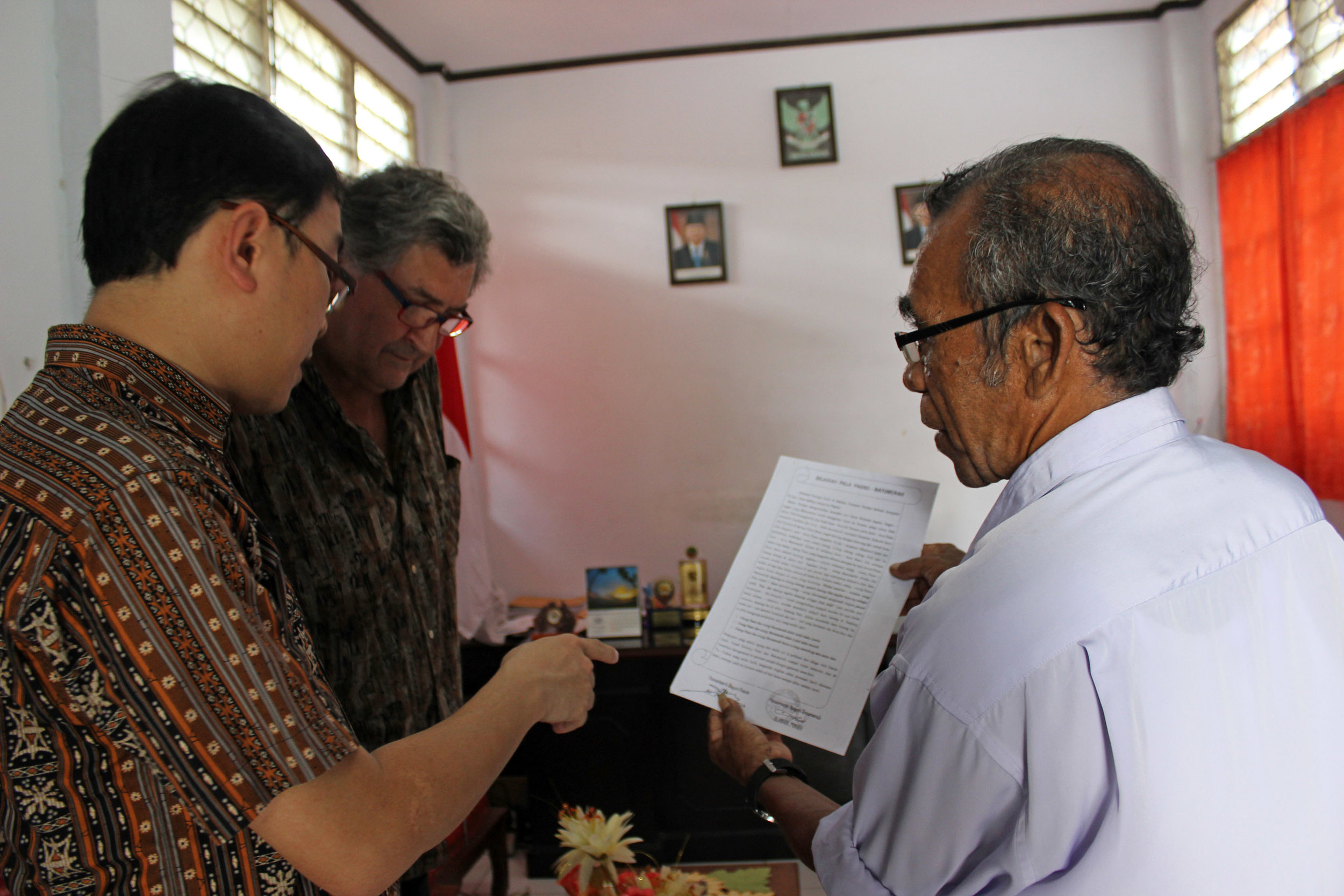

A local official from Passo village gives a copy of the pela covenant to Matius Ho (left) and Paul Marshall (middle).

In Passo, we were given a signed copy of their covenant. It reads[iv]:

History of Passo – Batumerah Pela

Before the Portuguese came to Maluku, the Kingdom of Ternate ruled Maluku, Irian (Papua), even as far as the Philippines.[v]

The Sultan of Ternate issued a decree to all vassal states under his rule that they should bring tribute to Ternate every year. In 1506, two kora-kora (traditional boats) sailed to Ternate: the Passo boat representing Patalima and the Batumerah boat representing Patasiwa. On their way back from Ternate, in the middle of the Buru Island sea, there was a strong wind and large waves. The Passo boat sank. Its outriggers were hit by the storm and waves. Shouts for help were heard. At that time, the Batumerah boat was behind Passo’s, so they helped the Passo people who began to drown and brought them to safety near a cape in Buru Island. The tagalaya (food containers) of the Passo people had been lost in the sea. Then, the Batumerah people opened their own tagalaya. Together with the Passo people, they sat down and ate together at the beach. They broke their sago stick, divided their fish, cut their coconut into two, and shared them. After the meal, the Passo people spoke out in tears, “Dear Batumerah brothers, you have helped us. May we acknowledge you as our Older Pela (“Pela Kakak”)?” Spontaneously, the Batumerah people responded lovingly, “Yes, you may, and we will acknowledge you as our Younger Pela (“Pela Adik”).”[vi] Then, they took an oath. To immortalize their oath, they turned over a rock at the cape. That cape is called Cape of Pela. As a result of turning over the rock, their fingers were cut and bled. They held together their bloody hands and spoke their sacred promise, consisting of:

1. Passo and Batumerah people shall not intermarry.

2. Passo and Batumerah people shall not fight one another.

3. Passo and Batumerah people shall help each other.

This sacred, great, and noble promise has been preserved and protected by the ancestors of Passo and Batumerah, down to the later generations. It has been kept from generation to generation, until now.

Oh loving God, don’t take away the love between us. May this love always grow in our hearts until the end of time.

Signature by the Head of Negeri (“Village”) Passo

Signature by the Head of Negeri (“Village”) Batumerah

This covenant still holds, as do many others. Christians and Muslims help one another, including in building churches and mosques. We were given photographs from several years before of the placing of the crescent at the top the nearby Agung An’Nur mosque. Amid street celebrations, the crescent was taken up a rickety, temporary ramp and, as a mark of honor, a Christian was asked if he would put it in its final place.

A celebration in Batumerah for the opening of a mosque, which some Christians from Passo also attended. A Christian was asked to put the crescent in its place atop the mosque (he complied). Photo courtesy of the chief of Batumerah.

This covenant explicitly includes love: “Oh loving God, don’t take away the love between us. May this love always grow in our hearts until the end of time.” At the same time, and with no sense of contradiction, its first article forbids intermarriage between the villages.[vii] This is not peace simply motivated by religious indifference or spiritual indolence. The villagers know that their respective beliefs are very different, they want to maintain their own religion, and they also strive to keep their children from leaving their faith, even to the point of forbidding intermarriage. But they help each other, and much more.

The current chief of Batumerah, who is both the king and the elected mayor, recounted this history to our small group. He then declared that “the Muslims around here are fanatics,” which surprised us since we already had been happily strolling around and drinking tea that afternoon with these “fanatics.”[viii] Then he added that “the Christians here are also fanatics,” and we realized that he simply meant that they were all deeply committed to their faith: he was assuring us that they were not diffident post-modernists but that their religion was central to their personal and communal lives and to their treatment of one another.

These relations show that secularity, the attempt to drive religion from the public square, is not a precondition for good religious relations. Pela relations call to mind Jacques Maritain’s stress on the importance of “civic friendship,” or John Courtney Murray’s view that the religion clauses of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution are “articles of peace,” not “articles of faith”—they are ways of living together, not fundamental doctrines.

But Pela goes beyond this. After advising us of the areas “fanaticism,” the chief of Batumerah then added one shared belief: “but we all believe we should love one another.”

Paul Marshall is the Wilson Distinguished Professor of Religious Freedom at Baylor University, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute’s Center for Religious Freedom, Washington, D.C, and a contributor to Religion Unplugged.

Footnotes:

[i] There was a recurrence of violence in 2011 but it was contained. See “Indonesia: Trouble Again in Ambon,” International Crisis Group, October 4, 2011.

[ii] Interview, Ambon, August 27, 2014. The State Institute for Islamic Studies is IAIN Ambon (IAIN = Institut Agama Islam Negeri) a proto-university.

[iii] One tentative listing of pela relations in the central areas of Maluku lists over 40 villages that have Pela relationships with one or more other villages.

[iv] Translation by Matius Ho, edits by Paul Marshall.

[v] Ternate is an island to the north of Maluku.

[vi] In Pela relations, one side is often referred to as the elder and the other as the younger.

[vii] The question of intermarriage in Pela relations is complex. Villages in a Pela relation can be understood in some senses to be of one blood, and so intermarriage would not be allowed for that reason. There are also Pela Gandong and Pela Bongso, “pela of the womb,” and these relations are understood of being of one common family or ancestry, which would restrict intermarriage. In Pela keras, “hard Pela,” a major covenant taken after a major event, such as exists with Batumerah and Posso, people are still allowed to marry within their own village, which would imply that the reason for restriction is not bloodlines. There are also situations where intermarriage is allowed according to adat, custom, but not according to agama, religion. This would imply that a religious restriction on intermarriage exists. For background, see Sumanto Al Qurtuby, Religious Violence and Conciliation in Indonesia: Christians and Muslims in the Moluccas (New York: Routledge, 2016), especially Chapter IV: Dieter Bartels, Di Bawah Naungan Gunung Nunusaku, jilid 1 (Jakarta: Gramedia, 2017).

[viii] Interview, Ambon, August 28, 2014.