On LA’s Skid Row, Portraits Of The Unhoused Are Turned Into Sacred Art

Jason Leith has had a knack for making art since he was in elementary school. He knew it in middle school and in high school. But when it came to choosing a field of study for college, Leith was conflicted.

While he loved creating, he also deeply enjoyed intercultural relationships and service work, making him consider becoming a missionary.

Before his first semester at Biola University in Los Angeles, Leith, a practicing Christian, prayed, asking whether he should do art or missions.

The response was clear.

“Finally, I heard what felt like a voice both within and outside of myself say, ‘you can do both,’” he said. “And instantly I had this rush of images through my mind of what ‘both’ looked like. It was making portraits of people as a way to connect with them and as a way to share hope.”

Leith’s desire to minister through portrait-making resulted in Sacred Streets, an art initiative based in Southern California that focuses on creating portraits of people in vulnerable situations. The portraits serve as both a relationship-building mechanism and a way to boost the visibility of those who are suffering.

After five years of what Leith calls “over-calculating everything and overthinking everything” that had to do with the portrait project, he met Steve.

Leith was exploring a vacant lot overgrown with grass one morning before class. As he walked, he saw that a man appeared to live at the back of the lot, against a cinderblock wall, covered by trees. He remembers the moment well.

“My heart jumped, and something happened in my stomach that was both excited and uncomfortable,” he said.

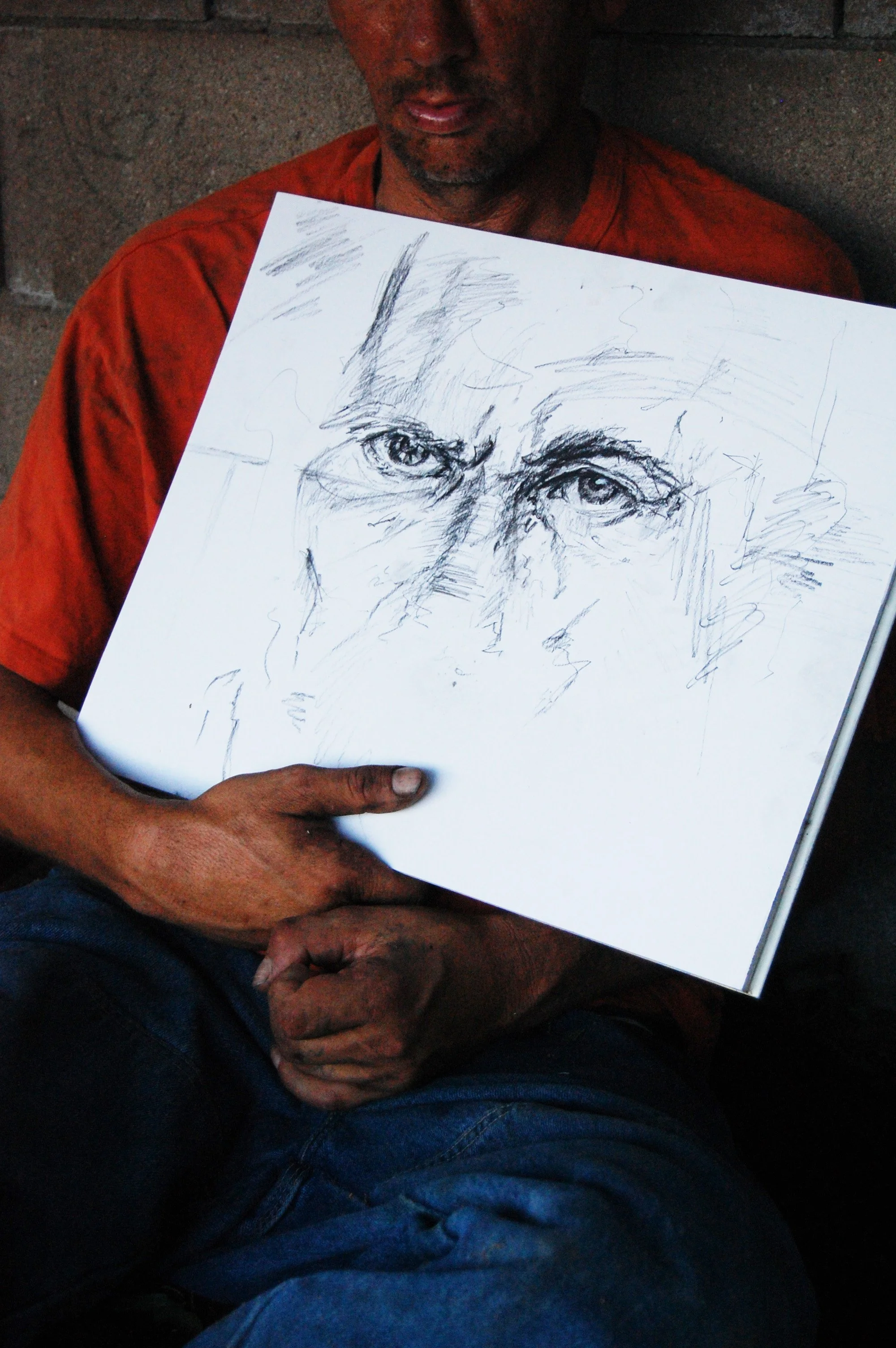

After running back to his car to get the only art supplies he had: a mechanical pencil and a few sheets of graph paper, Leith approached the man, introduced himself, and asked if he could draw his portrait. When Steve approved, Leith got to work.

After he had finished the drawing, Steve said to him, “Jason, when I’m with you, I feel human again.”

Photos courtesy of Jason Leith

Leith said that those words changed his life. He quickly decided what he would do for his senior art show; he was going to go to Los Angeles’s notorious Skid Row, meet 12 people, and make 12 portraits.

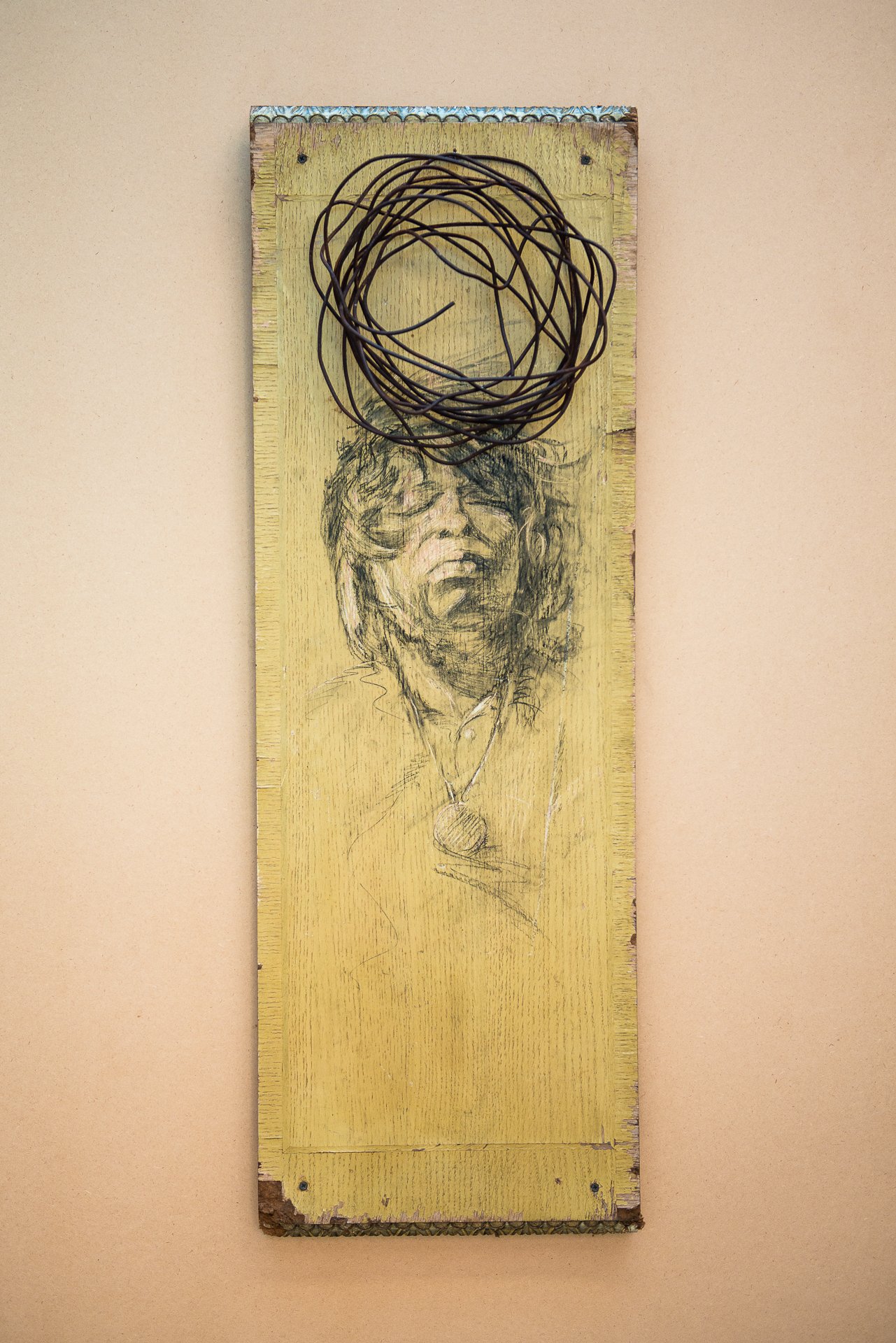

Thirteen years later, Leith is still drawing and connecting with people. He eventually began to incorporate found objects into his art, such as a roller chair, a hymn board, bits of wire, a suitcase, a children’s activity book from the 50’s, clay roof tiles, and several tents.

Leith estimates that he sees about half of the people he interacts with a second time—usually just the ones who have phones. But, for those with whom he has ongoing relationships, he generally only draws their portrait once—in the first conversation.

He said, “I like the drawing to be in progress almost the entire time of our first conversation. It becomes a way that the conversation just becomes richer. And I almost never do another portrait, but I love how it can be a way to create depth and connect in that first hour with somebody in a way that I don't think would be able to happen in a lot of other ways.”

During the portrait-making process, Leith explained that most people get progressively more comfortable — their shoulders relax, they make direct eye contact, and they smile more.

“The process of doing a face-to-face drawing is saying, ‘I see you, I notice you, I think you're important,’” he said.

Leith said he believes this noticing is so much more than a friendly gesture. Today, there are 187,000 people in California who are living without a home. Many of these people have been unhoused for years, even decades. But Leith has seen certain people finally leave the streets shortly after the dignifying work of having their portrait made.

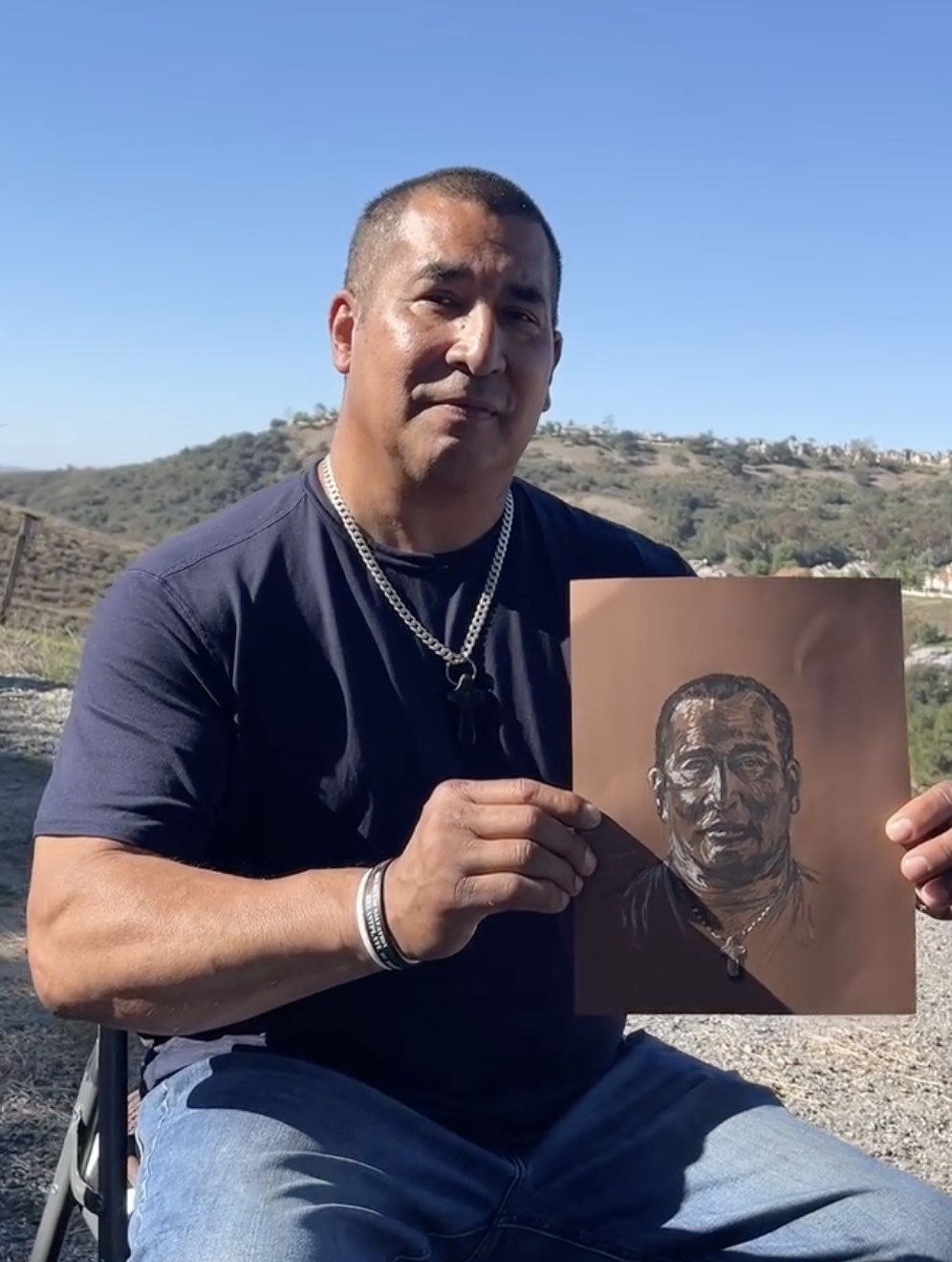

Photos courtesy of Jason Leith

While Leith has been able to form relationships with many of the men and women he paints, the art-making is meant to help more than just the portrait’s subject. It is also an opportunity to elevate the way other people view them.

“Maybe it's other people that need to see that they have this dignity and worth and value,” he added.

Aside from the technical expertise of his artwork, Leith elevates his subjects by using elements observed in iconographic imagery, altarpieces, and historical religious art at large.

Leith no longer solely focuses on people experiencing homelessness. Recently, he has been working with rescue missions, sketching individuals facing all sorts of hardships, including those recovering from addiction.

He is working on training 22 more artists in 2026 to do what he does. Moving forward, Leith’s goal is to make hundreds of relational portraits every year.

One of his hopes in training others is that he would be able to focus on creating what he calls “sacred spaces” to display the portraits. Leith was able to put together a gallery of his work in a parking lot in Skid Row, using trash and found objects to create a space that sought to emulate the descriptions of the New Jerusalem found in the book of Revelation. Leith’s dream is to create three of these galleries every year to display art done by those whom he has trained.

Leith has big dreams for his project. He hopes to train female artists to connect with survivors of sex trafficking and sex work, who he believes could benefit from portraits that remind them of their self-worth and identity.

He would also love to sketch teens aging out of foster care in the hopes that the art can “help their confidence, help them to see their value, their importance, and help them to fight for their future and how they see themselves.”

Leith’s artwork is for sale, but all funds go to the Sacred Streets nonprofit.

Leith is acutely aware of the power dynamics that occur when he draws people. He acknowledges that his race, gender, socioeconomic class, and American identity all play into the conversations he has, so he says he always tries to come into an interaction with a listening ear.

“A lot of people assume that I'm pretty much preaching the gospel every time that I go out and make these portraits,” said Leith, “but I am more hoping to give people an experience of the gospel.”

And often, he comes away gaining more than he gives.

“People think that people who live on the streets don't know God for some reason,” he said. “There's this idea that if you are living in poverty, you probably made some bad decisions in life and you probably don't know Jesus. … And that's the furthest thing from the truth.

“Most of the time I'm going in learning and having my faith built up so much by folks that have lived a life of resilience and are still alive today to tell the tale of how they are receiving God's grace, even at their lowest, even when they're suffering every single day.”

Matthew Peterson is Religion Unplugged’s podcast editor and audience development coordinator. He took part in this past summer’s European Journalism Institute held in Prague, an annual program co-sponsored by The Media Project.