'Reel Redemption' is the History Lesson on Faith-Based Films We Need Right Now

A scene from the 2016 movie Silence, directed by Martin Scorsese, starring Liam Neeson and based on the Japanese book of the same name, about two Catholic missionaries who travel to Japan in the 17th century in search of their missing mentor who is believed to have been promoting Catholicism amid harsh punishments for exercising Christian faith.

(REVIEW) In an era where faith-based filmmaking is becoming more and more of a force in the mainstream, it’s more important than ever that we know the history of this movement so we can talk about it intelligently. Unfortunately, most people critiquing Christian films or defending Christian films do so without a real appreciation of where faith-based films came from or why the faith community felt they needed to create their own industry.

Reel Redemption answers that need.

Reel Redemption is a new documentary that breaks down the history of the complicated (and sometimes contentious) relationship between Hollywood and Christianity in ways both academics and average viewers can learn from.

The first half of the documentary recounts in straightforward fashion the history of Hollywood’s relationship with faith-based films and audiences. The second half makes a shift and moves to analysis of the rising Christian film industry and the traditional film industry’s response. The result is a succinct primer on the history of American cinema’s relationship with Christianity that also adds to the discussion in insightful and edifying ways.

The documentary is written and narrated by Tyler Smith, film critic and host of the podcasts Battleship Pretension and More Than One Lesson. Smith is both a Christian and an adjunct film instructor at College of the Canyons and Chaffey College, a community college in Santa Clarita, California, so he’s unusually qualified to discuss the topics that Reel Redemption covers. I’ve met him a couple of times at film festivals, and reached out to him to see what inspired him to make the film.

“While there have been plenty of articles written about Christian film - some positive, mostly negative - it seemed somehow wrong to just be dismissive of it,” Smith said. “Even though I myself rarely enjoy Christian movies, they’re still art.”

Smith went on to say that people have often rightfully criticized Christian films for their quality, but he thought that was overshadowing other aspects of the genre that were worth exploring.

“With the documentary, I was hoping to make something that was a basic primer on film history while also exploring the cinematic landscape that allowed some Christians to feel that they needed to make a movie, and could actually succeed in doing so, both artistically and financially,” he said. “I wanted to give faith-based film its day in court, just like any other film genre, regardless of my own personal feelings about it.”

The 1928 silent film The Passion of Joan of Arc tells the saint’s story of braving the threat of torture to stand fast for her beliefs as a young woman in 15th century France.

The first half of Reel Redemption that deals with the history of the faith community making films is going to be the most impactful for many people. For those who’ve grown up watching Hollywood and Christians duke it out in the culture wars, it’s easy to think that there is some inherent tension between art and religion, or at least religious people and artists. For those people, some might be shocked to find out that it wasn’t always like that. Christians and Hollywood were very positive toward each other when the movie industry first began. And this relationship devolved overtime in extremely tragic fashion. Smith said:

“Christians weren’t actually suspicious of Hollywood early on. Like many other Americans, Christians enjoyed going to the movies. As shown in the film, Biblical epics were very lucrative for Hollywood. The spectacle was something that all filmgoers enjoyed, including practicing Christians. Their eventual suspicion of Hollywood came about as a function of several scandals, including the unsolved murders of William Desmond Taylor and Thomas Ince, but especially the trial of comedian Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle. Arbuckle was eventually acquitted, but the details of the Hollywood party scene that came out in the trial really scandalized more conservative Christians. They came to see Hollywood as a place of sex, drugs, and hedonism.”

The 1956 movie The Ten Commandments won an academy award for best visual effects.

As Reel Redemption tracks how this beginning suspicion along with industry and cultural shifts lead to Hollywood and the American slow break, there’s a poignant tragedy that the split between faith and filmmaking wasn’t inevitable. Faith and the arts are not naturally at odds. Tyler Smith handles this was a fair evenhandedness toward all the players involved, allowing the audience to decide for themselves who’s more to blame for this split, while clearly mourning that the split happened.

However, it’s when the film shifts to critique of the modern faith film criticism landscape that Smith’s own voice becomes clear-- and it’s one everyone should hear. Smith shows some of the most fair-minded analysis of Christian films that one is likely to ever read or watch. He never hesitates to call out Christian films for their sins (particularly calling out Pureflix as shameless). He also calls out secular film critics for their often unfair treatment of even good faith-based films:

“While I am often frustrated with fellow Christians for their eagerness to forgive the lower quality of faith-based movies due to their thematic content, I am also frequently frustrated when film critics are unable or unwilling to acknowledge those rare moments of artistic quality in a faith-based film due to its spiritual themes. Most film critics are both left-leaning and non-Christian and, like many of us, have a tendency to associate primarily, if not exclusively, with people that share their values. As a result, any values in a film that fly in the face of their personal beliefs are viewed as sort of artistic flaws. For example, in a secular culture of personal fulfillment, the idea of staying in a difficult marriage is viewed as oppressive, especially if it’s done for spiritual reasons. There have been some fairly effective Christian films produced in the last few years, but they espouse views that many critics deem socially irresponsible, so they can’t in good conscience recommend these films.”

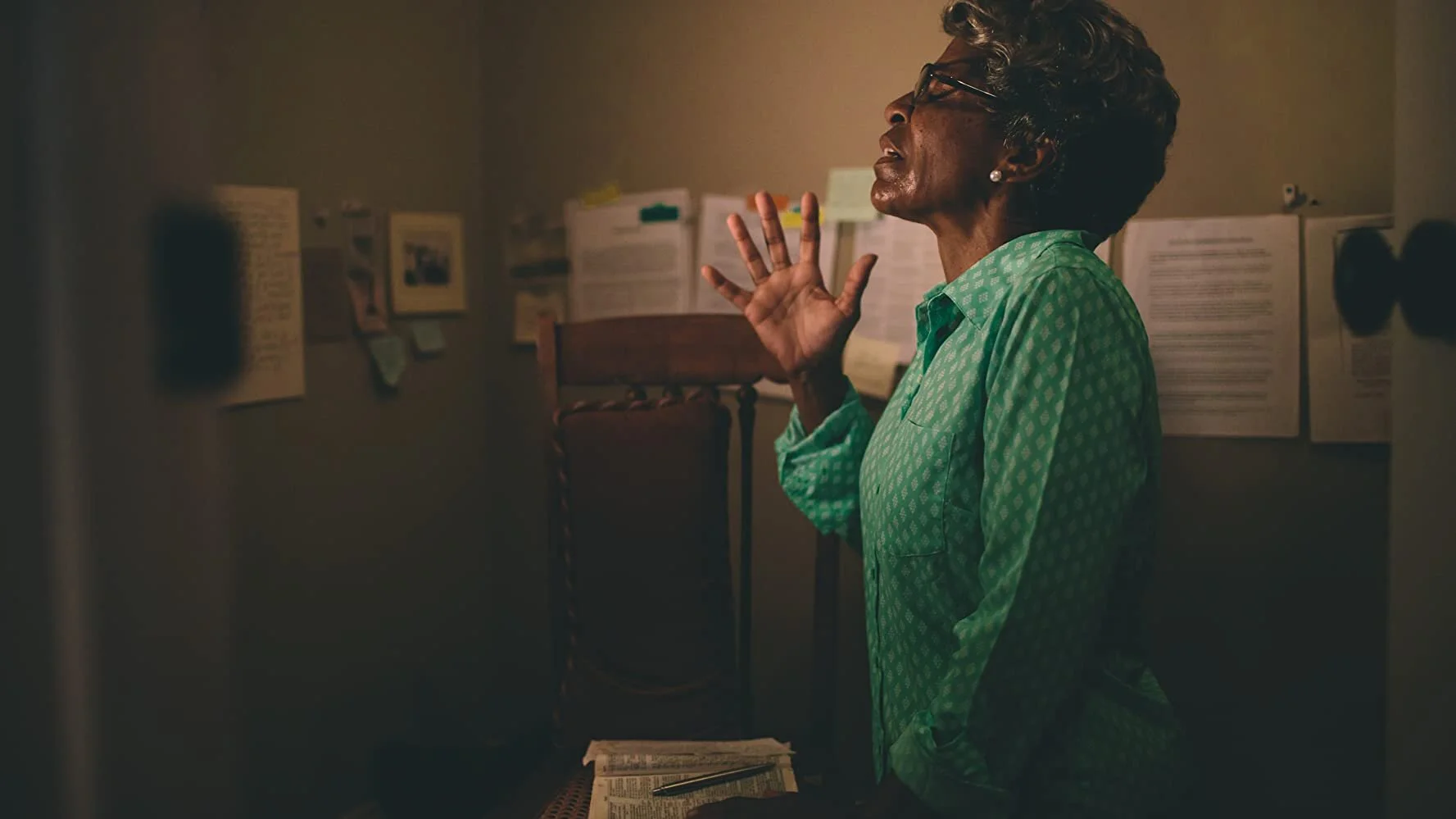

The 2015 American movie War Room grossed $74 million worldwide on a $3 million budget. It first released in Nigeria.

Also, beyond being fair-minded, Smith’s analysis of faith in film here is simply interesting. He notes many things many people who have seen the films probably have never considered before. For example, he argues that the devil can be effectively personified in film but God can only be effectively personified in film through the faith of his creatures. Tyler also compares Christian films to slasher films, noting that both genres started out playing to a specific subset of fans with very specific expectations and both were initially dismissed by critics before the genres grew and evolved. These and other ideas in the film make Reel Redemption interesting on its own terms beyond its contributions to ongoing debates about Christian films that other people started.

Because Reel Redemption is about the relationship between Hollywood and the Christian community, it doesn’t touch on representation of other faiths in cinema. That said, Smith believes that the desire for more diversity in filmmaking will mean that we will see a lot more religious beliefs represented very soon. He thinks that’s a great thing.

“If film is a ‘machine that generates empathy,’ as Roger Ebert described it, then the more points of view we get, the more we’ll be able to empathize with people very unlike ourselves,” Smith said. “So, yes, I think in the next five to ten years, you’ll see a lot more American films representing different spiritual perspectives. Undoubtedly, some viewers will see this as an affront, but I’m excited for it.”

Inevitably, Reel Redemption will not satisfy everyone. Many viewers will see Smith as too critical of Christian films and others will think him not critical enough. Many will also find that his shift from history to critique is too abrupt since he doesn’t really warn the audience it’s coming. However, for those who want the best breakdown out there of the history of American faith-based filmmaking, and real insightful critical analysis, in under 90 minutes, this is must-see viewing.

In the 2019 movie A Hidden Life, Austrian farmer Franz Jägerstätter faces the threat of execution for refusing to fight for the Nazis during World War II, citing his Christian faith.

The film ends on a note of true hopefulness for the industry that faith and filmmaking can reconcile their differences, and perhaps this whole rivalry was somehow also part of God’s plan for his glory. Smith expressed that same optimism when I talked to him:

“I am actually pretty hopeful about the faith-based film industry, partially because people can only be pandered to for so long before they start to demand more. I remember a friend of mine once said, ‘I don’t need a movie to tell me I’m right. I already know I’m right.’ I think the novelty of seeing our values up on the screen will wear off and the Christian audience will begin to demand something a little deeper.”

He also sees optimism on the side of Hollywood to be more open to exploring spiritual themes in their work:

“[A]s the Christian audience is now seen as a viable demographic, studios will greenlight more faith-oriented productions. As we saw with Noah and Exodus: Gods and Kings, Hollywood studios are desperately trying to court a faith-based audience, and are clearly willing to throw anything at the wall to attract it. This is exciting, because it has given filmmakers like Martin Scorsese, Terrence Malick, and Paul Schrader license to address their own spiritual preoccupations, producing some of the most thought-provoking films of the last decade. It’s unclear as to whether or not those films would’ve been made 10 or 20 years ago. This is actually a fascinating time to be a Christian who loves film. Theological questions are being addressed openly, and some really intriguing films have been made as a result.”

Hopefully he turns out to be right.

Reel Redemption is available to stream on Faithlife TV.

Joseph Holmes is an award-nominated independent filmmaker and film critic living out of New York City. He runs a blog, Overthinking Films, where he discusses how films connect to philosophy, society, and culture.