Saint or anti-semite? Maybe neither, G.K. Chesterton fans say

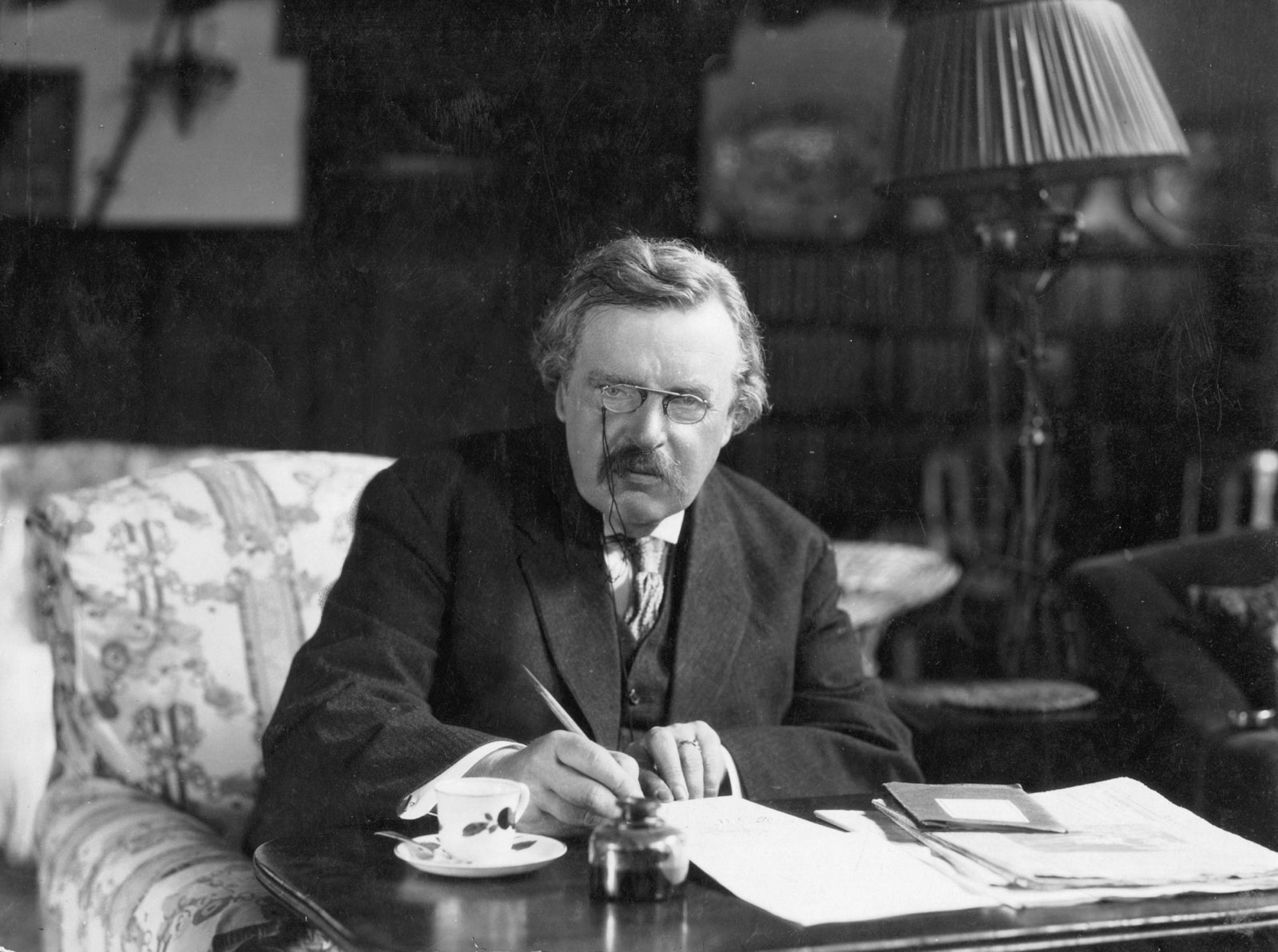

G.K. Chesterton. Creative Commons photo.

NEW YORK — Earlier this month, fans of the British Catholic author and journalist G.K. Chesterton met in Kansas City, Kan. for the 38th Annual Chesterton Conference.

On the meeting agenda: rave about the BBC adaptation of Chesterton’s best-selling priest-detective series Father Brown (now on Netflix), hear from keynote Chesterton lecturers and discuss the latest in an unlikely bid for canonizing the pipe-smoking, pub-going thinker as a Catholic saint-- chiefly, whether or not Chesterton’s writings mean he was anti-semitic.

Chesterton is known for articulating a sweeping, personal conversion from Anglicanism to Catholicism and for pithy, paradoxical quotes that should be common sense but often aren’t. He wrote about a hundred books, hundreds of poems, thousands of newspaper essays, some plays and art criticism.

He’s been up for canonization since 2013, an arduous process involving tests like the Vatican’s verification of miracles. Before a case is even opened, the Church collects biographical information, looking for evidence of particularly holy qualities.

Canon John Udris, a priest, spent this past year investigating the life of Chesterton, reading his works and speaking with his many fans and critics. Udris relayed the information to Bishop Doyle of Northampton (Chesterton’s diocese in England) to make the official decision about whether or not to open the case and take it to the Vatican. Doyle decided not to open Chesterton’s case for canonization.

“It’s not closed,” said Dale Ahlquist, President of the Society of Gilbert Keith Chesterton, in a phone interview. “It’s just not been opened. That’s the main thing you need to report!”

According to a letter Doyle wrote to the Chesterton society, there are three reasons the Church won’t open the canonization case:

There is no local cult following in Northampton, Chesterton’s Diocese.

There is no discernible pattern of spirituality that can be identified as guiding the life and works of the British author.

Chesterton is charged with being antisemitic.

While nearly all the conference attendees were disappointed, most were not surprised by the announcement. Ahlquist insisted that the bishop’s decision isn’t bad news because the society can still ask another bishop to take the case to the Vatican.

“[Doyle] has submitted his customary resignation, so there’ll probably be a new bishop there within a year,” Ahlquist said.

However, given Doyle’s conclusions, it’s likely another bishop would refuse to open a path to sainthood for Chesterton.

In response to the allegations of antisemitism, Ahlquist said that the charge comes from a sad misunderstanding of who Chesterton was, and “that it is not so much that Chesterton is antisemitic as it is that he paints with broad strokes.”

It was characteristic of many of the English writers of that time to write in over-exaggerated, almost flamboyant language and metaphors, Ahlquist said. Ahlquist thinks Chesterton’s writings show respect and care for the Jewish people, saying “his sin was not hating the Jews, but mentioning them.”

In The Everlasting Man, for example, Chesterton wrote highly of the Jewish people, saying that “the world owes God to the Jews.”

Chesterton’s critics find his depiction of the Jews as “foreigners” as deeply antisemitic. Adam Gopnik summarized Chesterton’s “troubling genius” in a 2008 New Yorker piece.

“He claims that he can tolerate Jews in England, but only if they are compelled to wear ‘Arab’ clothing, to show that they are an alien nation,” Gopnik wrote.

In his book Knight of the Holy Ghost: A Short History of G.K. Chesterton, Ahlquist attempts to answer this critique, noting that it comes from a misreading of Chesterton’s words and intentions.

“Chesterton accurately portrayed the Jewish people as a nation without a country, but it was distasteful to many that he would refer to them as foreigners,” he said. According to Ahlquist, when Chesterton referred to the Jewish people as foreigners, it was not because they were foreigners to him, but because they were foreigners to this world, as the Bible describes God’s people.

However, most Catholics agree that many great people, history-altering men and women, have been denied entrance into the communion of saints. It’s the Church’s highest award.

“There is no more rigorous peer-review process than canonization,” said Dr. Robert Carle, a professor of religious and theological studies at The King’s College in New York. “A person can be a servant and a great disciple without being a saint.”

“There’s enough question to be cautious about moving forward,” Dr. Carle concludes. In a post-WWII world, we have no choice but to view our heroes through the Holocaust. “Chesterton just doesn’t fit the image.”