Unpacking Kanye and Kyrie: Condemn antisemitic acts, but don’t destroy Black men

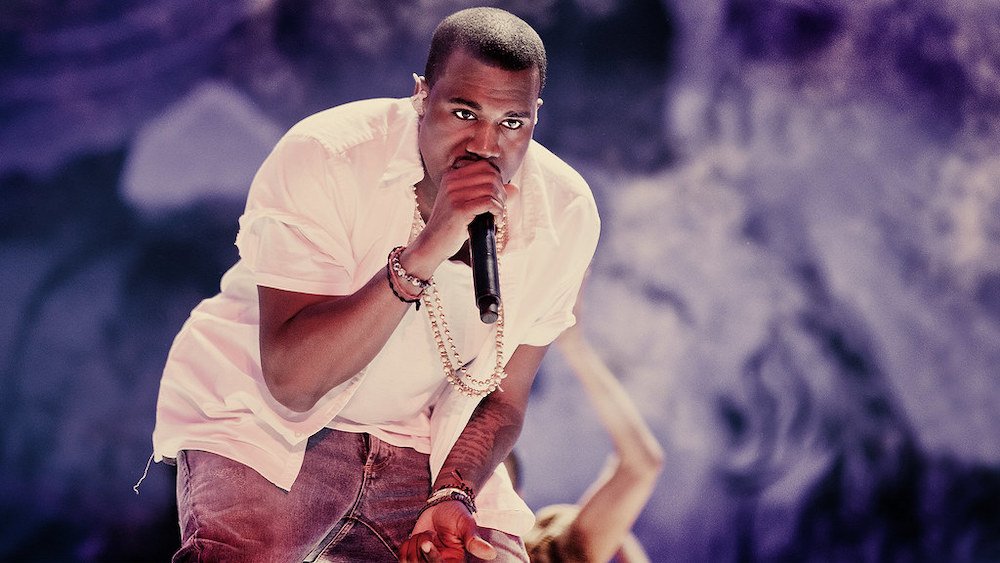

Kanye West, who now goes by Ye, in 2011. Creative Commons photo.

This story was originally published in the Forward. Click here to get the Forward's free email newsletters delivered to your inbox.

Religion Unplugged believes in a diversity of well-reasoned and well-researched opinions. This piece reflects the views of the author and does not necessarily represent those of Religion Unplugged, its staff and contributors.

(OPINION) What exactly was antisemitic about the tweets and statements of Kanye West (now known as Ye) and Kyrie Irving over the past few weeks? Despite being antisemitic in tone, did any of these statements contain some degree of truth? How appropriate was the reaction against both Black men? And could the Jewish reaction to antisemitism by Black celebrities have unintentional consequences to relations between Black gentiles and white Jews?

There have been several attempts to unpack the events of the past few weeks and the reactions to them. Here is mine. I’ve numbered them like a legal briefing, though I have no intention of appearing in any courtroom.

1. Kanye’s original tweet was antisemitic. Threatening to go “death con 3” against any group of people is unambiguously hate speech.

2. But Kanye’s reference to African Jews in antiquity needs to be unpacked because it may not have been antisemitic, at least initially. It’s offensive to state that Black Africans are the real Jews and that European Jews are impostors. But that’s not what West said in his initial tweet.

He stated, “The funny thing is I actually can’t be Anti Semitic because black people are actually Jew also.” Parsing Ye may be a fool’s errand, but by “also” — italics mine — he could have meant “Blacks are Black, and they also are Jews,” or “Blacks are Jews, along with European Jews.” Although that remark immediately sparked outrage, he did not then state that European Jews are not Jews.

West aside, it’s not offensive to assert that there were Black African Jews caught up in the slave trade because the statement is true. Of the estimated 12.5 million Africans shipped to the New World during the height of the slave trade, there unquestionably were Jews among them, if only a small minority. Centuries of Jews and Muslims commingled along trade routes deep into the continent, Lewis Gordon, the founder of the Center for Afro-Jewish Studies at Temple University who now heads the philosophy department at the University of Connecticut, told me. “It’s false to state that claiming there were Black Jews in Africa is antisemitic because there were Black Jews in Africa. It would be like saying, ‘there were Black Muslim slaves in Africa’ is Islamophobia.”

Black African Jews existed in antiquity, and the Diaspora created European Jewry as well. Both identities can be, and are, real.

It is crucial to avoid generalizations, beginning with the erroneous assumption that normative Judaism is white, and that questions challenging that, particularly those made by Black people, are inherently antisemitic.

3. The film “Hebrews to Negroes: Wake Up Black America” promoted by Kyrie Irving is antisemitic in its Holocaust denial alone. I haven’t watched it, so I will take on faith the claims from those who have that it states the Holocaust never happened. How far it takes the “real Jews” argument above, I don’t know. What makes little sense is why Irving had to tweet about it at all — just as what could possibly have been his urgent need to earlier declare to his millions of basketball fans that the world is flat.

4. It’s inappropriate to label the claim “European Jews are impostors” as a universal belief of “Black Hebrew Israelites” because …

5. The term “Black Hebrew Israelite” is a conflation of many different groups who believe and practice many different things. The term generally refers to descendants of newly emancipated African Americans who rejected the Christianity of their former slaveholders. Some claimed Jewish lineage, and some embraced Judaic practices without converting halachically.

But not all groups lumped under the term today all share the same practices and beliefs. Chicago’s Beth Shalom B’Nai Zaken congregation describes itself as “Conservadox” and is regularly visited by mainstream Jews. Its rabbi, Capers Funnye, is halachically Jewish, though he was ordained under Israelite auspices. His congregation has no connection or resemblance to the Israelite School of Universal Practical Knowledge, known for confronting white Jews about their legitimacy on the streets of New York.

In a backgrounder on its website, the Anti-Defamation League makes this distinction upfront, stating “Black Hebrew Israelites are not the same as Black Jews or Jews of color” (a different issue that to my dismay, still has to be explained), and that “Not all Black Hebrew Israelite organizations are antisemitic or extremists.” But the section goes on to group all of them together, saying “Black Hebrew Israelites believe that they are the true Israelites and that the Twelve Tribes of Israel are people of color.” Not all do. As with any religion, belief and practices — such as animal sacrifices by ancient Hebrews — change over time.

“There is, in fact, no such thing as a Black Hebrew Israelite, or at least any one thing, and the phrase is not an accurate descriptor in an historical sense,” Bruce Haynes, a sociology professor at the University of California and the author of “The Soul of Judaism: Jews of African Descent in America,” wrote in the Forward earlier this year. “As used today, the term is largely a conflation of many different groups that hold wildly different beliefs.”

6. Groups labeled as Black Hebrew Israelites are not the only religious bodies outside of rabbinic Judaism who claim a descendancy from Biblical Israel. The Book of Mormon, upon which the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints is based, is Joseph Smith’s divinely inspired, but unproven, account of ancient Hebraic people who settled in the Americas a millennium before Columbus. Mormons do not call Jews impostors, but they do call non-Mormons Gentiles, including Jews.

7. There have been Black people condemning Kanye and Kyrie. Of particular note is that it took Charles Barkley to get NBA head Adam Silver to act on suspending Irving. Joining the outrage are commentators from LeBron James and Jemele Hill. But West and Irving also have their defenders, and nuancing it further, some back Kyrie but not Kanye. That’s especially true given West’s alliance with Donald Trump and his anti-Black statements and actions, including his “white lives matter” fashion stunt immediately preceding the current controversy. Many Blacks say that should have sparked the same outrage as his antisemitic tweets.

There is no one universal Black opinion. Yet…

8. Many Black people are also troubled by the public condemnation of Black men, regardless of how badly they have behaved. OK, millions of African Americans will accept that O.J. murdered Nicole and Ron Goldman (or was held legally responsible for their deaths) and that Bill Cosby raped white women (or was convicted of doing so before the evidence was tossed). But many Black people have long felt that media and white society as a whole revel in the downfall of Black men, particularly the most successful among them. Forcing Irving to apologize publicly, no matter how deserved, felt to many like extracting a pound of flesh in a slave pen.

I would add, however, that sentiment is cooler toward West, who has consistently denigrated the Black community with antics as harmful to Blacks as his death con threat is to Jews.

9. Kanye and Kyrie brought their troubles on themselves. Maybe I’m in the wrong crowd, but I don’t know anyone who woke up, when this escapade began, dying to read what Kanye or Kyrie thought about Jews. I can’t explain Irving’s motivations, except that maybe he failed to notice nobody ever got a job from a tweet, but plenty of people have lost them. With Kanye, I suspect the real reason behind his behavior is to get attention (he was and is still part of the Kardashian clan). If so, it worked.

10. Jewish organizations’ mobilization against antisemitic acts are effective in the short term. But will it really change anything? Robin DiAngelo dissects America’s failure-to-communicate on racism as white people and Black people seeing racism two different ways. Whites, she maintains, define racism as bad acts by bad people, such as saying the N-word or putting a noose on a co-worker’s desk. Black people certainly recognize those behaviors as racist. But they also see institutional racism, such as Black youth being tailed in store aisles or banks denying loans to Black doctors, as equally harmful. Most whites, DiAngelo says, are oblivious to that.

To that Robin’s thesis I add this Robin’s corollary: Mainstream Jewish organizations are excellent at responding to individual bad acts of antisemitism. They are less effective at dismantling antisemitism institutionally, or at least publicly. There are endless individual bad acts of antisemitism, and responding to them all is as effective as plugging an ocean — or more to the point, attempting to silence social media. Responding disproportionately to those by Black people may seem to yield short-term victories, but it risks alienating erstwhile allies who certainly know racism when they see it, and have a pretty good idea about antisemitism as well.

11. I haven’t covered every nuance here because it would be impossible to do so. Yet it is crucial to avoid generalizations, beginning with the erroneous assumption that normative Judaism is white, and that questions challenging that, particularly those made by Black people, are inherently antisemitic. As I have long stated, to say “Blacks and Jews” is a misnomer: The two groups are not mutually exclusive. They weren’t in antiquity, when Black Jews traveled along Africa’s trade routes, nor today, when everyone should know at least one Black Jew.

Robin Washington, an acclaimed veteran journalist based in Minnesota, is the Forward’s Editor-at-Large. A longtime senior editor, columnist, radio host and documentarian across mainstream and ethnic media, he was one of the founders of the Alliance of Black Jews and an early pioneer of the term “Jew of color” more than two decades ago. Contact him at rwashington@forward.com or follow him on Twitter @robinbirk.