Why it’s unlikely U.S. mainline Protestants outnumber evangelicals

(ANALYSIS) It’s almost become a cliche at this point, but it bears repeating again - measuring religion is hard. No matter if you're a social scientist who uses qualitative methods like interviews and focus groups or have a quantitative approach that relies on survey data. Religious classification is nearly impossible. Creating categories that are meaningful enough that they make sense to the average person, but not too many categories that people get easily confused is a herculean task. That fact has risen to the foreground in some recent data that was released by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI).

The one finding from their surveys that got the attention of lots of people on social media was that Protestants who do not identify as evangelical Christians have risen fairly substantially over the last few years, and now they outnumber the share who identify as evangelical Protestants. But that was immediately met with some skepticism by those who dug into the details of their classification methodology. In short, the question they face is one that all quantitative scholars of American religion face: if you are a Protestant, but you don’t want to be identified as an evangelical, do those people form a coherent religious group?

In the academic understanding, there are three types of Protestants - evangelical, mainline and historically Black Protestants. Thus, when I do data analysis, I sort Protestants into one of those three buckets. The approach that I tend to employ is called RELTRAD and it uses the religious denomination to parse people into different categories. Thus, to be a mainline Protestant is to be a member of a religious denomination that scholars have deemed to typify the mainline brand of Christianity. Examples of this are the United Methodists and the Episcopalians.

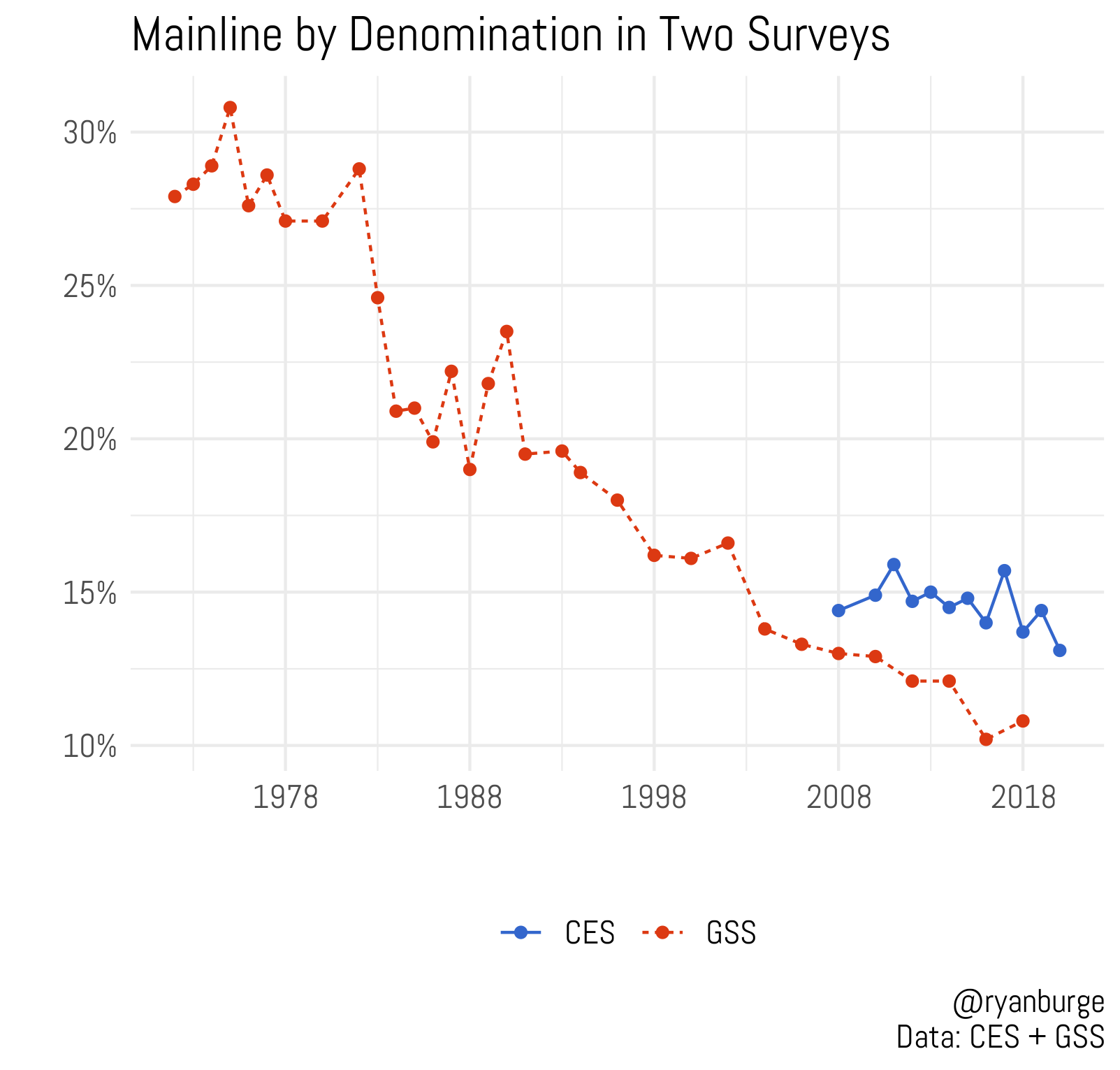

There are two primary surveys that afford researchers the ability to sort mainline Protestants based on religious tradition. The General Social Survey, which dates back to 1972. But also the Cooperative Election Study which began in 2006. Both surveys ask a branching series of questions that help us understand if someone is a Southern Baptist vs. American Baptist or a United Methodist vs. a Free Methodist. This is key when generating an estimate of mainline Protestants.

As can be seen, they both tell the same basic story about American mainline Christianity - it’s in decline. In the 1970s, the GSS indicates that over 30% of all Americans could be classified into a mainline denomination. But that quickly changed. By the late 1980s, the share of the mainline dropped below 20%. In the most recent estimates, the mainline was just about 10% in 2016 and increased very slightly in 2018 to just over 11%. The CES estimates are slightly higher for the mainline, but also show a downward trajectory. About 14% of Americans were mainline in 2008, but that’s down to 12% in the most recent data. But there’s general agreement in these surveys - mainline Protestants have declined over time and are probably between 10-13% of the population today.

However, there’s another approach to measuring the mainline, which was employed by PRRI. Instead of asking a series of branching questions that probe what denomination people are affiliated with, there’s a simpler two question approach. The first question is about broad religious tradition. This includes response options like: Protestant, Catholic, Mormon or Atheist. Then, respondents are asked if they identify as “evangelical or born-again” or not. If they say that they are Protestants and self-identify as evangelical, then they are evangelicals. But, if they say they are Protestant but don’t identify as evangelical, then they are mainline. Using this approach compared to the denominational strategy can lead to slightly different estimates.

According to the CES, between 14% and 16% of Americans were mainline using either definition in a period running from 2011 through 2017. However, in the most recent waves of the CES there has been some separation forming between the two groups. Those who identify as Protestant but don’t identify as evangelical have dropped to 12% in both 2019 and 2020, while the share who are classified as mainline has stayed relatively steady around 14%. Thus, these two strategies arrive at similar, but not identical estimates.

I have to admit that surveys are not completely accurate. Social desirability bias is a serious concern when it comes to measuring religion. People may lie about their actual religious affiliation and say they are Protestant when they haven’t been to church since they were a teenager. Additionally, many people are probably not entirely sure what kind of church they actually attend. As more and more churches are shedding denominational labels, who can blame them?

However, we can try to validate our survey numbers by comparing them to another data source. Most denominations have been organizing and publishing statistics on their membership for decades. That’s certainly the case with the Seven Sisters of the Mainline: The American Baptist Church, the United Church of Christ, the Disciples of Christ, the Episcopal Church, the United Methodist Church, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of American and the Presbyterian Church (USA). I did my best to find membership statistics over the last 10 years for each tradition. In some cases, I had to expand my time frame, however.

There is one clear and unmistakable conclusion - the largest traditions in the mainline are losing members at an incredibly rapid rate. The United Methodists lost 2.25 million members over 10 years, a 15% decline. The ELCA dropped 750,000, a decline of 22%. The PCUSA is down 40% between 2009 and 2020 and the Disciples of Christ are also down 40%. In fact, there’s only one tradition - the American Baptists, where membership is only down single digits over the last decade.

While the Seven Sisters do not represent all the mainline traditions in the United States, they constitute a vast majority of this religious group. This analysis alone indicates that there are six million less members of these seven traditions than just a decade ago. It’s hard to conceive of a situation where these denominations are losing hundreds of thousands of members each year, yet the overall mainline tradition is growing in size.

But denominational statistics are not bulletproof. Anyone who has been in the leadership of a local church can attest to that. Many churches fail to submit their membership numbers each year. Many who do may fudge those numbers just a bit to make their losses look less severe. Many churches never purge their membership roles, even when someone has not been at a church service for a decade or more.

Thus, there’s just no right answer for how many evangelicals, mainline Protestants or atheists there are in the United States. Every survey firm has their own approach to these questions based on their own understanding of the religious landscape. The only way to get a more accurate picture is to look at all the data holistically. If a number of surveys show that X group is growing larger, but a new survey comes out that says they are getting much smaller, it’s appropriate to interpret this new data with a bit of caution. If other surveys begin to show the same result, then we can have more certainty of an actual change in American religion. We all are trying to do our best. We want an accurate portrait of American religion. But this is a hard job.

Ryan Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University, a pastor in the American Baptist Church and the co-founder and frequent contributor to Religion in Public, a forum for scholars of religion and politics to make their work accessible to a more general audience. His research focuses on the intersection of religiosity and political behavior, especially in the U.S. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanburge.