Zimbabwean Pastor-In-Training Delivers Groceries During COVID-19

Pastor-in-training Gladys Kwedyo on a grocery delivery trip.

Wearing a surgical mask, Gladys Kwedyo doesn’t get out of her car when she reaches the town of Chitungwiza, 17 miles from her home in Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe. She turns off the eerily empty main road onto a narrow, more worn-out street and pulls right up to a house where an outdoor funeral is going on. No one is social distancing.

She calls out to one of her church congregants and gently reprimands the woman for leaving her house.

“I think a disaster is looming,” she says. Kwedyo instructs the congregant to grab a bag of groceries from the boot of her car. She joins her in a short prayer and then takes off. She has three more church members to visit.

The reason Kwedyo, a 60-year-old church pastor-in-training, remains in the car is not because of the coronavirus. It is because she cannot walk.

Polio robbed her of the use of her legs when she was 2 years old, but she never allowed the disability to stop her from having a fulfilling career and marriage or going into church ministry. Now, as a pandemic has effectively shut down Zimbabwe and the rest of the planet, she won’t allow her disability to stop her from helping those in need. She has a hand-controlled car, two hands and a big heart.

“I do things because they have to be done,” Kwedyo says, speaking about her life in general. She speaks of her passion for helping the less fortunate, which started many years ago when she joined the compassion ministry at her church. “We’d cook three big black pots on a Saturday and go to town and feed the ‘street kids’ — they weren’t as many of them back then,” she recalls. “I’ve never felt disabled. When there’s something that needs to be done, I think, ‘Why not me?’” Kwedyo says she and a few other women from church usually cook for the entire congregation every Sunday, but now, due to the financial crisis and food shortages in Zimbabwe, she mainly looks after the four families to whom she delivers groceries.

“I can’t recall the experience of walking because I was too young,” Kwedyo says, “but I’ve seen photos.” Her Zimbabwean parents were living and working in Zambia, but they headed home for the birth of their second child — they wanted her to carry their nationality and pride. When they returned to Zambia, there was an outbreak of polio, and Kwedyo was one of many children who suffered but survived in 1962. Despite her parents' attempts at various methods of physiotherapy, Kwedyo never walked again.

Kwedyo describes how in many African homes, children with disabilities are often the cause of marital problems, as partners blame each other for the disability and the child is seen as a burden, a curse or an embarrassment. “My parents gave me a new Shona name [after I became disabled]: Rufaro, which means we are happy.”

Kwedyo attended a boarding school for the disabled, Mukuwapasi Clinic, in the small town of Rusape. When asked if she thinks her father’s decision to place her there was good for her, she pauses to think, then hesitantly replies, “Yes. When you’re different, you are the center attraction, and people can laugh at you. We were all different — wheelchairs, crutches, different disabilities. No one laughed.” After five years, she moved to an able-bodied boarding school, as her mother wanted her closer. “My mum would carry my wheelchair, my bag and me to the bus. The bus drivers never let us pay the bus fare — not once,” Kwedyo says.

Kwedyo, second from the left, with friends.

Kwedyo now drives herself in a silvery gold hand-controlled Toyota. “I never thought I’d drive, but my mum told me, ‘Whatever others are doing, you can also do,’” she says. She remembers ordering her first car, a red Mazda 323 with a black interior, straight from Japan. This was when she was working as an administrator for TelOne, a government-owned telecom company formerly known as Post and Telecommunications Corporation — she worked there from 1981 until her retirement five years ago. She is now a pensioner and spends her time rearing chicken, managing a property she built in her backyard and giving back to the community. She leads the Chitungwiza branch of His Presence Ministries International church with her pastors, the Kimbinis, and another female pastor-in-training. But she makes this grocery run on her own.

The next congregant, a blind woman, 65-year-old Chengeto Muguti, is not at home. Kwedyo hears from neighbors that she has gone to weather the storm of the pandemic in a rural area. She leaves the groceries with a young man at the house. Kwedyo points out that the entire time she was in Chi-town, as it is popularly known, she does not remember seeing a single mask, sanitizer or pair of gloves. She also notes that she saw several children and teens gathering to play in the street.

Kwedyo at her pastor-in-training ordination.

As a child then a teenager, attending an able-bodied school was harder for Kwedyo. She describes it being cold and difficult to navigate, as she was the only disabled pupil at Mount St. Mary’s in Wedza.

“The bathrooms were by the dormitories. I’d make my way on my crutches, and by the time I came back to class the lesson would be over,” she says. “It got a little bit better two years in, when my parents got me a wheelchair.” She recalls making friends because many of the children wanted to push her wheelchair. “The school was on a mountain, and the form one and two [eighth and ninth grade] classes were on the lower level, but I was worried about how I’d get to the classes on the upper levels as I got older.” When she returned for 10th grade to find the headmaster had switched the classroom structures just for her, she says she felt overwhelmed with love and accepted.

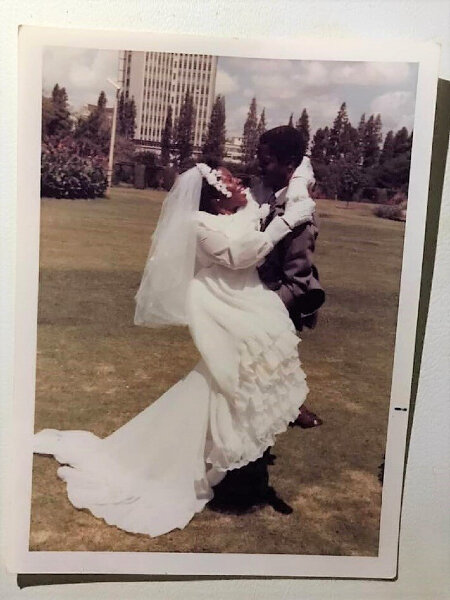

Kwedyo and her husband on their wedding day.

While she was working at TelOne, she met the man who would soon become her husband, Aloise Kwedyo. “I didn’t want to get married,” she says, “so after two years of dating, when I saw he was getting serious, I dumped him.”

When they got back together several months later, Kwedyo says Aloise went straight to speak to her aunt and then her father about marriage. In Zimbabwean tradition, the bride-to-be usually tells her aunt (her father’s sister), who would then pass the message on to her brother. Kwedyo recalls her father also broke tradition by requesting to speak to her husband directly. Usually a groom does not even attend the lobola negotiations, let alone speak to the father of the bride — this is all done through elder male relatives.

“My father told him, ‘You realize my daughter will be served by you and not the other way around — even your mother, she will be doing that?’ Aloise said yes, he’d considered this and was personally prepared, as I would be living with him.” Kwedyo’s father was referring to the tradition in which a new bride in the family is usually given the household chores and made to serve the husband’s family. Many times, this tradition is used to abuse young women.

“My mum was shocked when I told her about me getting married, and I said to her, ‘Why are you shocked? You told me I’m just like everyone else. Other young girls are getting married, and so why shouldn’t I?’” Kwedyo laughs as she remembers this. Thinking back to their conversation about marriage, she reflects, “That’s when I realized how difficult [raising me] must have been for her. She was stressed and anxious for me, but she let me go.” Kwedyo says her mother gave chores to her and her six siblings equally when growing up — laundry, dishes, cleaning the floor. No exception was made for her.

Kwedyo says she and her mother-in-law, who arrived at the end of the wedding celebration when they were packing the gifts, had a strained relationship. A few years into the marriage, her mother-in-law arrived at their office with a new prospective wife for Aloise. Aloise sent his mother a letter, saying, “This is the wife I have chosen, and since you cannot accept her, I am no longer your son.”

Kwedyo delivers groceries to Sheila Mutoma, in the middle.

Aloise did not speak to his mother for three years, but Kwedyo says she held on to the teachings of her church — to always repay evil with good, and to love even those who persecute you. She facilitated the mending of her husband’s relationship with his mother, and Kwedyo herself helped nurse her mother-in-law until she died. Her husband had a stroke a few years later. He spent two days in the hospital, then passed away at 39.

As she drops off groceries to her third congregant of the day, Kwedyo says, “Sekuru Gurwe survives by collecting plastic. He gets $1 per kilogram.” When asked how much one Zimbabwean dollar is in U.S. dollars, she explains that the black market rate is constantly shifting, and can even change multiple times in a single day. The currency crisis in Zimbabwe has gotten even worse with the pandemic and subsequent lockdown.

“The government should be looking after the less privileged, senior citizens and those in the disabled categories,” Kwedyo says. She recounts how she’s heard rumors that the government may be giving out cash and that it would be distributed by local councilors.

But when Kwedyo drove by the council office to inquire, no one knew anything about the rumored $180 per family, in Zimbabwean dollars. She left the names of her congregants in case the councilors did start an aid program, but she points out that 4.5 pounds of chicken costs $200 in Zimbabwean dollars, so it wouldn’t make much difference.

As her grocery delivery trip nears its end, Kwedyo says she has been stopped more than once by surprised residents who asked her what she was doing, as none of the other churches had come to help. “There’s no help at all,” she says.

Kwedyo then describes a vivid memory she has. “A crippled man was dragging himself from Market Square to First Street [in Harare]. I was coming to get my passport picture taken when I parked my car and saw him. I failed to get out of the car because I’d break his heart.”

Kwedyo with her dog, Fluffy.

She says she is conscious that many people with the same disability as her have had less fortunate fates. She knows of a girl who was locked in a room for 18 years because her parents were embarrassed of her.

The day she saw the man dragging himself on the street, she called a security guard close by and asked him to ask the man what he wanted. “He wanted a pie, so I gave the security guard the money, watched him buy and give the man the pie, then I drove off. I could get my [passport] picture done another day,” she says.

Her fourth and final stop is at Sheila Mutoma’s home. The 32-year-old, who lives with her elderly mother, was left paralyzed on the left side after a stroke.

“Right now [with the pandemic], somehow everyone is in the same category, able-bodied and disabled,” Kwedyo says, referring to Zimbabwe’s food shortages and price hikes. According to Kwedyo, these problems have escalated since the lockdown. “The shopping centers [in the suburbs] are just as bad as Chi-town when there is a subsidized mielie-meal delivery.”

Mielie-meal is the country's staple food, and Kwedyo says people are willing to brave close-contact queues because they cannot afford the regular mielie-meal. “Things are bad,” she sighs.

Kwedyo says she will brave another trip to deliver groceries again soon. “I have so much to contribute to anyone [able-bodied or disabled]. The Lord has been good to me.” Kwedyo has lived up to her name, Rufaro — she is happy.

Zoe Ramushu is a filmmaker-writer from Zimbabwe and South Africa currently based in New York, where she studied journalism at Columbia University.