Jackie Robinson's forgotten Christianity: How being a devout Methodist impacted his life

NEW YORK — A lot has been said and written about Jackie Robinson. The baseball great — famous for breaking baseball’s color barrier — was known for many things. Robinson’s athletic abilities, courage in the face of racism and the dignity with which he went about it all remain the focal points.

What is often ignored, and even forgotten, was Robinson’s Christian faith.

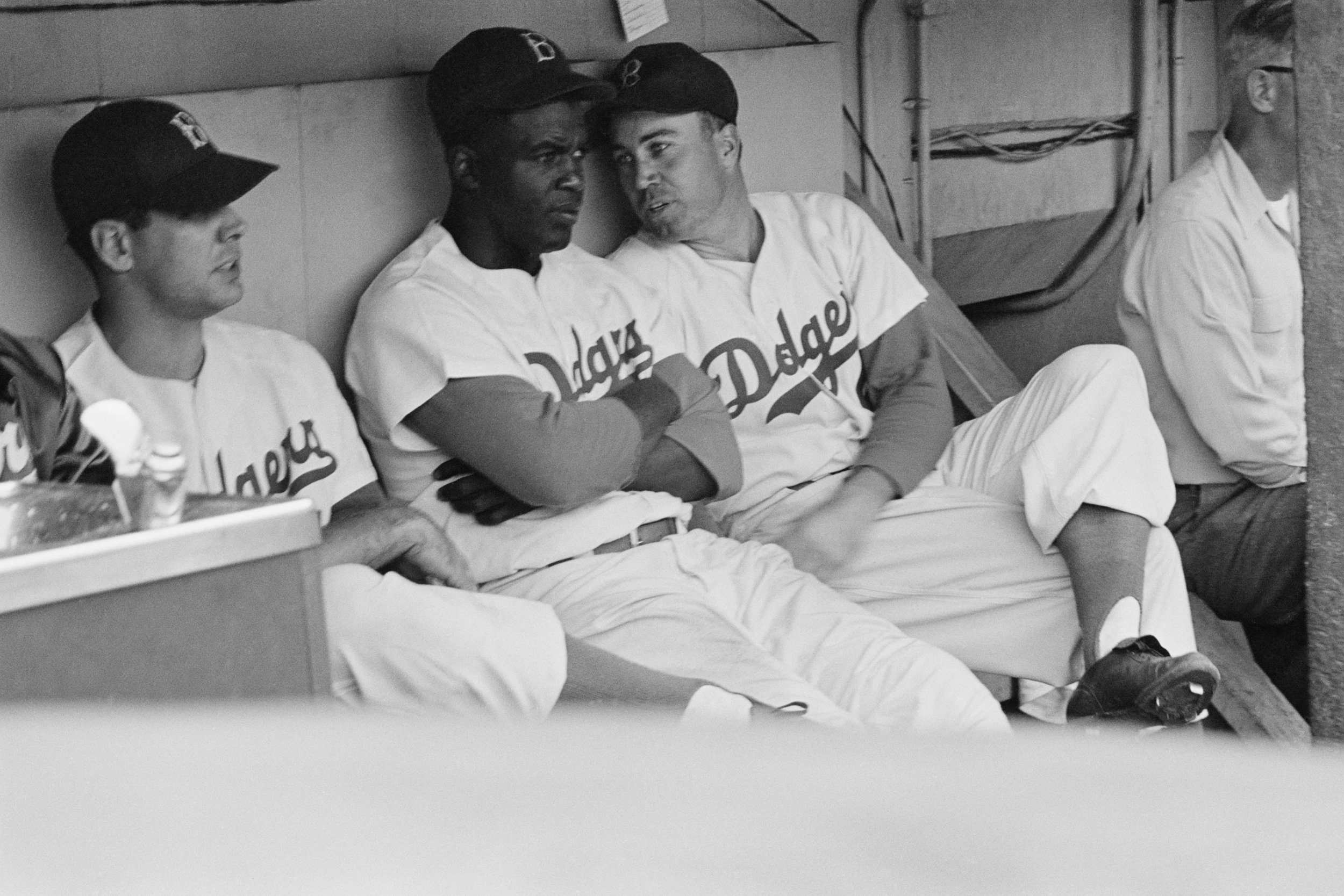

This past January 31 marked the day the trailblazing Robinson would have turned 100. He died at age 53, meaning that he’s been gone almost as long as he lived. Robinson’s breaking of baseball’s color barrier on April 15, 1947 when he donned a Brooklyn Dodgers uniform — that now-iconic No. 42 emblazoned across his back — at Ebbets Field and how his relationship with Branch Rickey, the team’s general manager, forever changed race relations in the United States.

“I think there are different explanations why his faith has been ignored. One of them is that Robinson — unlike Rickey — was private about his religion. It wasn’t something he talked a lot about,” said Chris Lamb, who co-authored a book in 2017 with Michael Long entitled Jackie Robinson: A Spiritual Biography. “The book of Matthew quotes Jesus as telling us to avoid praying publicly. Secondly, Robinson’s significance comes more in his work in baseball and in civil rights and not in religion. That said, he couldn't have achieved what he did without his faith and his wife Rachel.”

The centennial of Robinson’s birth (and the many events associated with the celebration that will culminate in December with the opening of a museum in his honor in New York City) has allowed Americans of all ages to recall Robinson’s great achievements in the diamond — including helping the Dodgers win the 1955 World Series and having his number retired by every Major League Baseball team in 1997 — and the impact he would have on ending segregation and helping to spur the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s. Robinson died of a heart attack in 1972 at the age of 53.

Robinson’s famous quote — one etched on his tombstone at his Brooklyn gravesite in Cypress Hills Cemetery — reads: “A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives.”

Robinson’s life did have an enormous impact on others, a legacy that continues to this day. He was more than hits and steals, although his .311 lifetime batting average and 1962 induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame rank him among the best ballplayers in history. An exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York, which runs through September, offers fans a glimpse of his playing days through photography and video, providing a window into the media’s portrayal of Robinson at that time.

Aside from being one of the greatest American athletes, this groundbreaking athlete also made history off the field. In doing so, Robinson became a target of racist taunts from spectators and by many unwilling to accept that an African-American man should play alongside white players.

It was in the early 1940s that Robinson met nurse-in-training Rachel Isum Robinson when both were students at the University of California at Los Angeles. The couple wed on February 10, 1946. From the moment Robinson entered the major leagues, the couple faced insults to even death threats. Later in life, both Robinson and his wife became involved in the Civil Rights Movement.

Growing up in Pasadena, Calif., Robinson was influenced by a minister named Karl Everitt Downs, a pastor at Scott Methodist Church where the budding ballplayer’s mother Mallie attended services. It was that relationship that led Robinson to Christ and made him a believer. It was Downs’ influence that helped Robinson develop his faith and Methodist upbringing.

“When athletes today point up to the sky after a home run or a touchdown catch or a great basketball play, it is an egotistic action: ‘Look at me, aren’t I great?’” said Lee Lowenfish, a baseball historian. “It has nothing to do with God looking down on all competitors, the winners and the losers, the gifted and the not-so-gifted.”

Robinson’s faith is not totally lost on everyone. Eric Metaxas, a radio host and bestselling author, highlighted Robinson’s piety in his book, Seven Men: And the Secret of Their Greatness. Robinson is one of seven historical figures Metaxas examined — which also includes George Washington and Saint Pope John Paul II — and how the ballplayer’s faith played a central role in his ability to combat racism.

Meanwhile, historians and academics like Lamb, a journalism professor at Indiana University-Indianapolis, have pointed out in the past how pop culture, sports journalism and Hollywood have often left Robinson’s religion out of his life story. For example, the movie 42 — the 2013 Robinson biopic — doesn’t spent too much time exploring Robinson’s religion. A four-hour Robinson documentary directed by Ken Burns released three years ago also barely mentioned the faith angle.

In 42, Rickey tells his head scout he plans to sign ballplayer. The reason behind such a controversial decision? “Robinson’s a Methodist. I’m a Methodist. God’s a Methodist. We can’t go wrong.”

Rickey, known for his own devout Christian faith, never uttered those words. Hollywood filled in some of the blanks there, historians said, but it was put there to make a point. What is true is that Robinson and Rickey were both Methodists, each relying on their respective faith to overcome threats in return for the promise of ending racial segregation.

“Interestingly, in 1950 when the movie The Jackie Robinson Story came out with J.R. playing himself, Robinson is shown in a couple of scenes asking ministers for advice… Those scenes [now] seem very wooden but there is some semblance of truth in them,” said Lowenfish, author of the 2009 book Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman.

What did happen, Lowenfish recounted, was a deep-rooted bond that was formed between Robinson and Rickey based on an “intense personal religion” — they both shared the same faith tradition — that was genuine and no longer “in vogue these days.”

“Robinson and Rickey were genuine Christians, muscular Christians certainly, but Christians in their concern for their fellow human beings,” he added. “It was no act when Rickey read the passage from Giovanni Papini’s biography The Life of Christ to a skeptical Robinson at their historic first meeting in Brooklyn on August 28, 1945.

What kept Robinson from lashing out at the vile taunts from the stands? Lowenfish said although Robinson’s “first response would always be to go on the attack to vile insults, Rickey convinced him that ‘turning the other cheek’ and playing as hard and well as he could was the best response.”

Following his retirement, Robinson became more public about his faith. In 1962, during a speech to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Robinson said, “As the first Negro in the majors, I needed the support and backing of my own people. I’ll never forget what ministers like you who lead [the] SCLC did for me.”

As important as ministers were in supporting the Dodgers first baseman, Lamb said it was Robinson’s faith in God that was so vital throughout the players’ life.

“No athlete faced greater pressure and dealt with more hatred than Robinson,” he said. “How did Robinson succeed? There’s little doubt that faith played a significant role in this success.”