Satanic Panic Drives A Small Town To Unjust Violence In ‘Stranger Things 4’

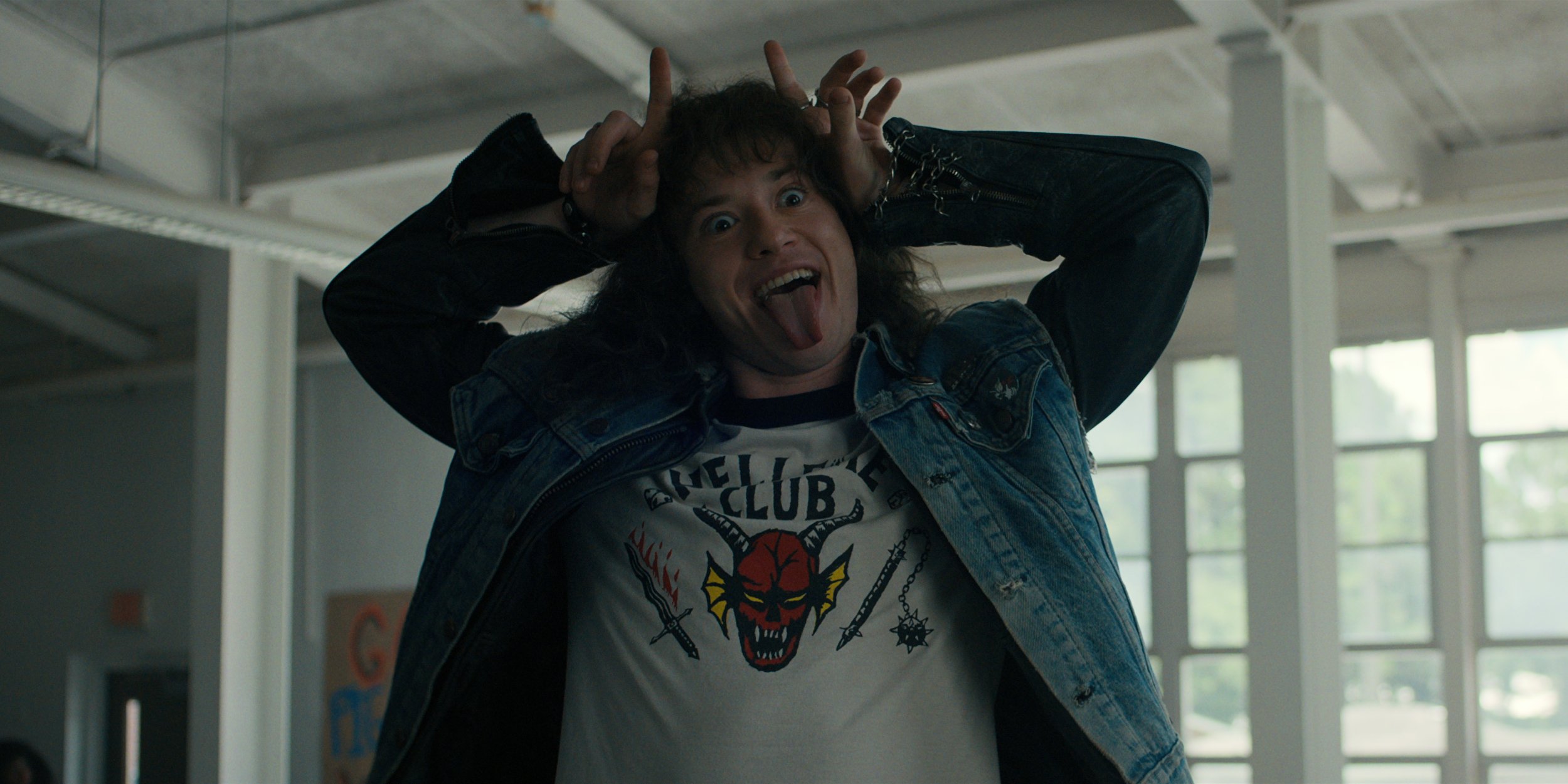

Eddie Munson (Joseph Quinn) in “Stranger Things.” Photo courtesy of Netflix.

As new episodes of “Stranger Things” come to Netflix after three years, the audience is teleported back to the 1980s. New Kate Bush fans are born, we all share a collective nostalgia for roller rinks and we unlock the fear of satanic ritual in schools and neighborhoods.

One of those things is much darker than the others, intentionally so. The satanic panic serves as the historical backdrop of this season, causing the entire town to erupt in period-typical hysteria when high school students start dying again.

The fictional lens allows for a new perspective on a historical phenomenon. Ultimately, it also proves that religious fearmongering of any kind is never biblical but is almost always cowardly and selfish.

The Cold War has been an important historical setting for the entirety of “Stranger Things.” Russian experiments and KGB enemies create threats hand-in-hand with the monsters of the Upside Down, playing off real fears of the decade.

If there’s any fear of the 1980s greater than the Russians, it’s the devil — which is why it’s important that the satanic panic plays such a large role in the new season.

The satanic panic, a media-fueled hysteria, advanced the idea that underground groups of Satanists were performing ritualistic child sacrifices and influencing the world through rock music, day cares, serial killers and the tabletop game Dungeons and Dragons. Some of these fears were based on fact — killers Son of Sam and Charles Manson claimed to have been motivated by the devil — but most were just fears, based on conspiracy and larger political and cultural shifts.

Though largely unfounded, these fears heavily impacted the day-to-day lives of Americans. Curfews were implemented, certain music was condemned, D&D was banned by churches and homes. In Hawkins, Indiana, where “Stranger Things” takes place, this culture of fear is ever-present: A magazine article in Newsweek magazine proclaims D&D “the devil’s game,” and talk runs rampant about the game’s supposed negative effects, including violence, sodomy and murder.

Hawkins certainly has a unique problem with supernatural forces. Over the course of three seasons, countless have died — a majority of whom were kids and teenagers. Characters often say the town is cursed, which is very nearly true.

With satanic panic sweeping the country and the real threat of demons in this small town, do the residents of Hawkins prove that there’s a fundamental truth to these religious fears? Do they rise up together to defeat evil in God’s name?

Nope. Not even close.

A meeting of the Stranger Things’ Hellfire Club. Photo courtesy of Netflix.

It begins with the Hellfire Club, the D&D group at Hawkins High. It’s a perfect narrative beginning, primarily because the tabletop game was one of the main recipients of undue fear and reactionary condemnation in the decade. It also offers a nice starting point for main characters Mike, Dustin and Lucas, who are all huge nerds (I say that as a compliment).

Multi-year senior Eddie, who leads the Hellfire Club, soon becomes the sole witness to the death of cheerleader Chrissy. It’s clear to the audience that her death is caused by a new, nefarious creature from the Upside Down.

It just isn’t clear to the other residents of Hawkins.

Chrissy’s boyfriend Jason quickly claims the “freak” Eddie must have a spiritual connection to the devil. He is a D&D player, after all.

“Stranger Things” often employs dramatic irony to create higher suspense. The audience has seen the demonic creature that must be defeated and usually, thanks to the main characters, knows what needs to be done to defeat it. The audience also sees parents, teachers, law enforcement and others who have no clue what’s going on panic and work against the ultimate goal.

In this case, the suspicion and mistrust begins a vigilante manhunt for Eddie. Jason and other basketball players swear they’ll kill Eddie as soon as they find him. In the process, the demon — referred to by characters as Vecna, representative of the devil — kills one of the basketball players. Though it’s clear Eddie had no hand in it, that seals his fate.

It culminates in a frighteningly provocative speech Jason delivers spontaneously at a town hall meeting. He calls on Romans 12:21 — “Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good” — to get the town to join in on his manhunt for the members of the Hellfire Club. They all agree.

The dramatic irony employed means the audience has a “God’s eye view” of sorts over all the proceedings. Most importantly, it shows just how stupid all of the people of Hawkins look for reacting the way they do.

Often, while reading about the satanic panic, I try to offer some empathy to the American families caught up in the fear of the era. I wonder about the political and social environment, about the culture of fear that surrounded in the news. I try to imagine there was something unavoidably real causing that kind of panic.

This season of “Stranger Things” made it clear that isn’t true. An entire town was terrified and driven to motivated violence because of what boils down to preconceived notions of high school popularity and tabletop gaming.

Even worse, they actually are facing an explicit, demonic threat. They don’t call a priest, listen to an expert, proceed with caution or even decide to investigate. They just decide they’re going to turn against a teenager who they don’t know and who’s facing his own share of hardship.

In “Stranger Things” and in the real world, these large-scale threats of safety that rely on little facts and lots of fear are just that: reactions based on fear. They aren’t smart, and they especially aren’t in pursuit of actual righteousness. Hopefully seeing that from the outside serves as a warning of sorts not to fall prey to that sort of fearmongering, no matter who it’s coming from.

And D&D isn’t of the devil — it’s just a nerdy tabletop game!

Jillian Cheney is a contributing culture writer for Religion Unplugged. She also writes on American Protestantism and evangelical Christianity and was Religion Unplugged’s 2020-21 Poynter-Koch fellow. You can find her on Twitter @_jilliancheney.