Getty Museum's Christian Manuscripts Exhibit Sees Antisemitism Where There Is None

(REVIEW) Images from 31 unique ancient objects, including Christian manuscripts in Latin, the Getty’s treasured Rothschild Pentateuch in Hebrew and two printed Hebrew books — all dated between 1040 and 1592 — are on display in the “Painted Prophecy” show at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles until May 29. Some of these objects have never been displayed before.

The Christian images in the show are from a wide variety of sources, some from Psalters — books of psalms recited by priests and religious people at various hours — some from Books of Hours commissioned for private devotion by wealthy lay people, and others from medieval histories and commentaries. There is even an odd travel book dated 1592 — 10 years after Columbus’ voyage that led to Europe’s discovery of the American continent — titled, “America, Part 3: Accounts of Voyages to Brazil.”

Initial A: Judith with the Head of Holofernes, about 1450, from Bible, Gold leaf, tempera, and black ink on parchment, Leaf: 36.7 x 26 cm (14 7/16 x 10 1/4 in.), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. Ludwig | 13, fol. 165v (83.MA.62.165v)

Theodor de Bry, German, born Flemish, 1528-1598, Adam and Eve in America, 1592, from “America, part 3: Accounts of Voyages to Brazil” Closed: 33 x 24 x 3.4 cm (13 x 9 7/16 x 1 5/16 in.) Getty Research Institute 87-B24379

Aside from a framed sketch of the heroine Judith that was prepared as a print illustration, most of the images in this collection are bound into books that manuscript experts call codices — plural for codex, the name applied to any handmade ancestor of the modern book.

If you are in the L.A. area, it is well worth a visit to get a close look at these images for their intrinsic interest and charm.

Anyone who wants to look closely at a selection of the show’s images can start online with an index of all the works in the show and then can search for them by name at the Getty website.

You might, however, want to ignore the Getty’s interpretative materials because they seem intended to push a misinterpretation of the Christian images as works of antisemitism and misogyny — based on little or no evidence. Space does not allow for refutation of all the erroneous claims in the curator statements and texts associated with the show. So I’ll focus on examining one particular image, which clearly does not portray what the Getty commentary claims it portrays and is innocent of all the sinister connotations attributed to it. It can stand for other similar unfounded misinterpretations that space does not allow me to address.

Tour the Exhibition

Watch the guided video tour of “Painted Prophecy” by curator Larisa Grollemond.

“A Jew Praying and the Virgin and Child”: one example of misinterpretation

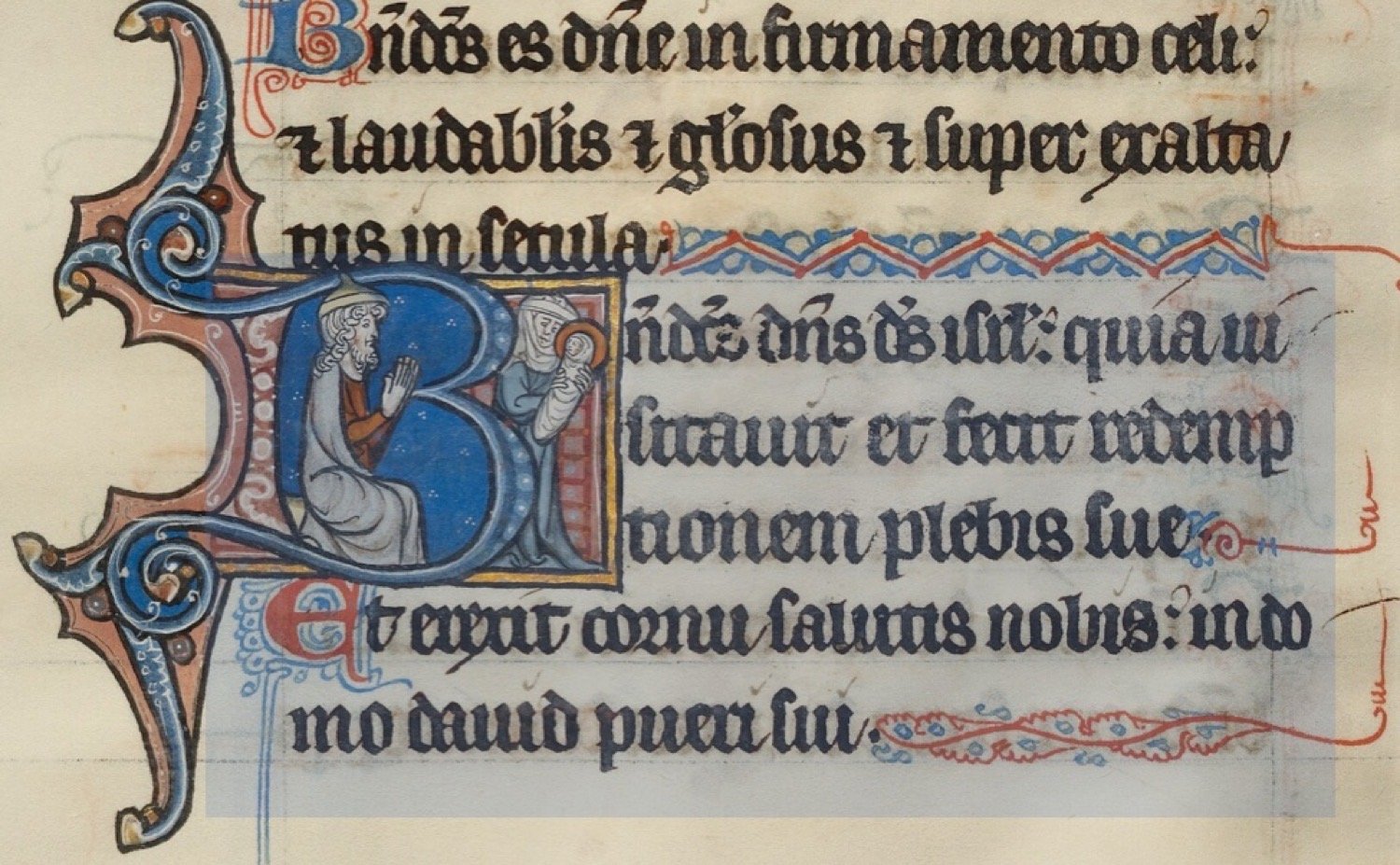

In the initial B illustration from the Bute Psalter, the initial B contains the image of a praying man with the pointed hat worn by Jewish men in the Middle Ages against a blue background of stars. To the right of the B, a veiled woman without a halo holds a swaddled baby with a halo.

In the gallery label, the image in the initial B is described as “a visual retelling of a legend in which a man of Jewish faith miraculously comes to recognize Christ as the Messiah.” The record for the page says “A Jew praying to the Virgin and Child.” From deciphering some of the Latin, I can assure you these statements are wrong.

To begin with, the initial B is not the initial letter of a psalm from the Old Testament but of a New Testament “canticle,” or liturgical song. It is actually the initial letter of Benedictus, the initial word of the Canticle of Zachary given in Luke 1:68-79.

Clearly then, in spite of what the Getty’s label says, the actual story that begins with the initial B is not a medieval legend. It is from a New Testament story that starts when Zechariah, a Jewish priest, is offering a sacrifice in the temple, and the angel Gabriel appears and announces that Zechariah and his aged wife Elizabeth will have a child. When Gabriel tells Zechariah his child of his old age will go before the Lord to prepare his ways, Zechariah is stricken dumb for not believing the angel.

Nine months or so later, the Benedictus canticle was Zechariah’s song of thanksgiving after he named his son, John, with the name given to him by God through the angel. When Zechariah’s tongue was loosened, he burst out singing this canticle of praise, which begins:

Benedictus Dominus Deus Israel; quia visitavit et fecit redemptionem plebis suae et erexit cornu salutis nobis, in domo David pueri sui.

Blessed be the Lord God of Israel; because he hath visited and wrought the redemption of His people: And hath raised up a horn of salvation to us, in the house of David his servant.

After the gallery label incorrectly states what the letter B image means, an uncalled-for implication of antisemitism is added with these words: “The scene takes on a sinister connotation considering the medieval practice of forced conversions and the eventual expulsion in 1306 of Jewish people from France, where this manuscript was made.” The so-called sinister connotation is also completely made up.

The image is definitely not a subtly insidious depiction of a random Jewish man miraculously coming to faith in Jesus and praying to Jesus’ mother, as is claimed. Instead the image portrays the known New Testament figure Zechariah praying in thanksgiving within the initial, while to the right of the initial, his aged wife Elizabeth holds their haloed miraculously born child, St. John the Baptist.

One would hope for a more accurate scholarship from curators of ancient manuscripts — including a knowledge of the religious beliefs written about and of the Latin and Hebrew languages — since an understanding of the texts is essential for a true understanding of what the images convey.

“in spite of what the Getty’s label says, the actual story that begins with the initial B is not a medieval legend.”

The Rothschild Pentateuch and the Abbey Bible: Genesis retold in Hebrew and Latin

The star of the show is the Rothschild Pentateuch, which was an important acquisition by the Getty in 2018, the first Hebrew manuscript to enter its collection. On the main webpage for the show, the exhibit is said to bring the Christian manuscripts into dialogue with the Rothschild Pentateuch about “the medieval Christian understanding of Hebrew scripture.”

One topic of dialogue that could have been better explored is the art-historical significance of the difference between the types of images included in the Hebrew and Latin texts. For example, following is a comparison between the images on opening pages of Genesis from both the Rothschild Pentateuch and the Abbey Bible.

Both the Hebrew and the Latin manuscripts are illuminated, which by the strictest definition means they contain images that are gilded or silvered. The reflectivity of precious metals illuminates the text both figuratively and literally. Over time, the term “illuminated” began to be applied to manuscripts with painted images, gilded or silvered or not. In the Hebrew manuscript, individual letters are gilded too.

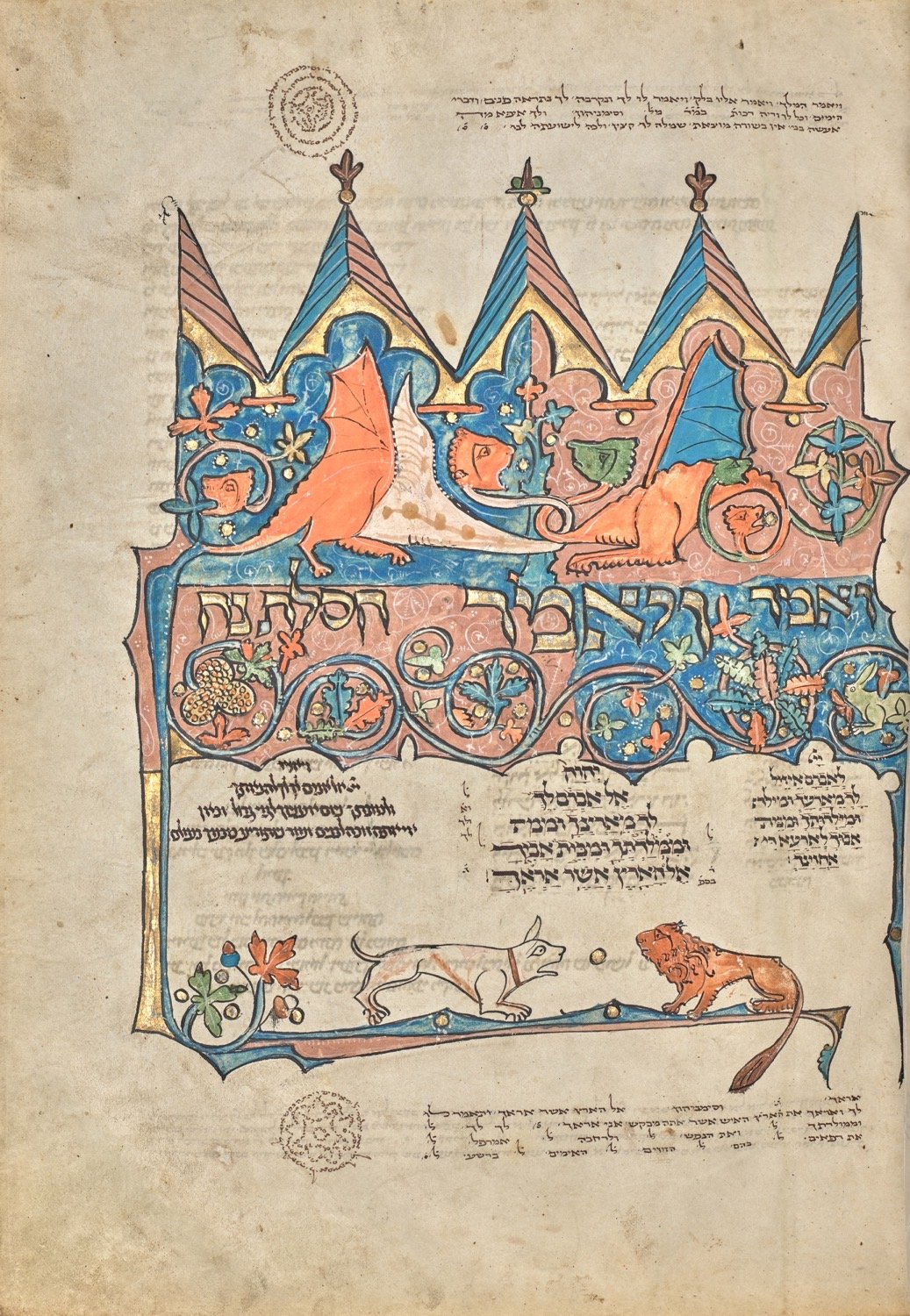

Some Hebrew texts in the Rothschild Pentateuch example page are written in complicated patterns and surrounded by interpretive commentaries in minuscule lettering. Comical figurative images around the texts are apparently meant to decorate and amuse, as they do not illustrate the serious narrative text, which describes God’s creation of the world.

Image 1: Decorated Text Page from the Book of Genesis, 1296, from Rothschild Pentateuch, Tempera colors, gold and ink on parchment, Leaf: 27.5 x 21 cm (10 13/16 x 8 1/4 in.), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Acquired with the generous support of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder, Ms. 116

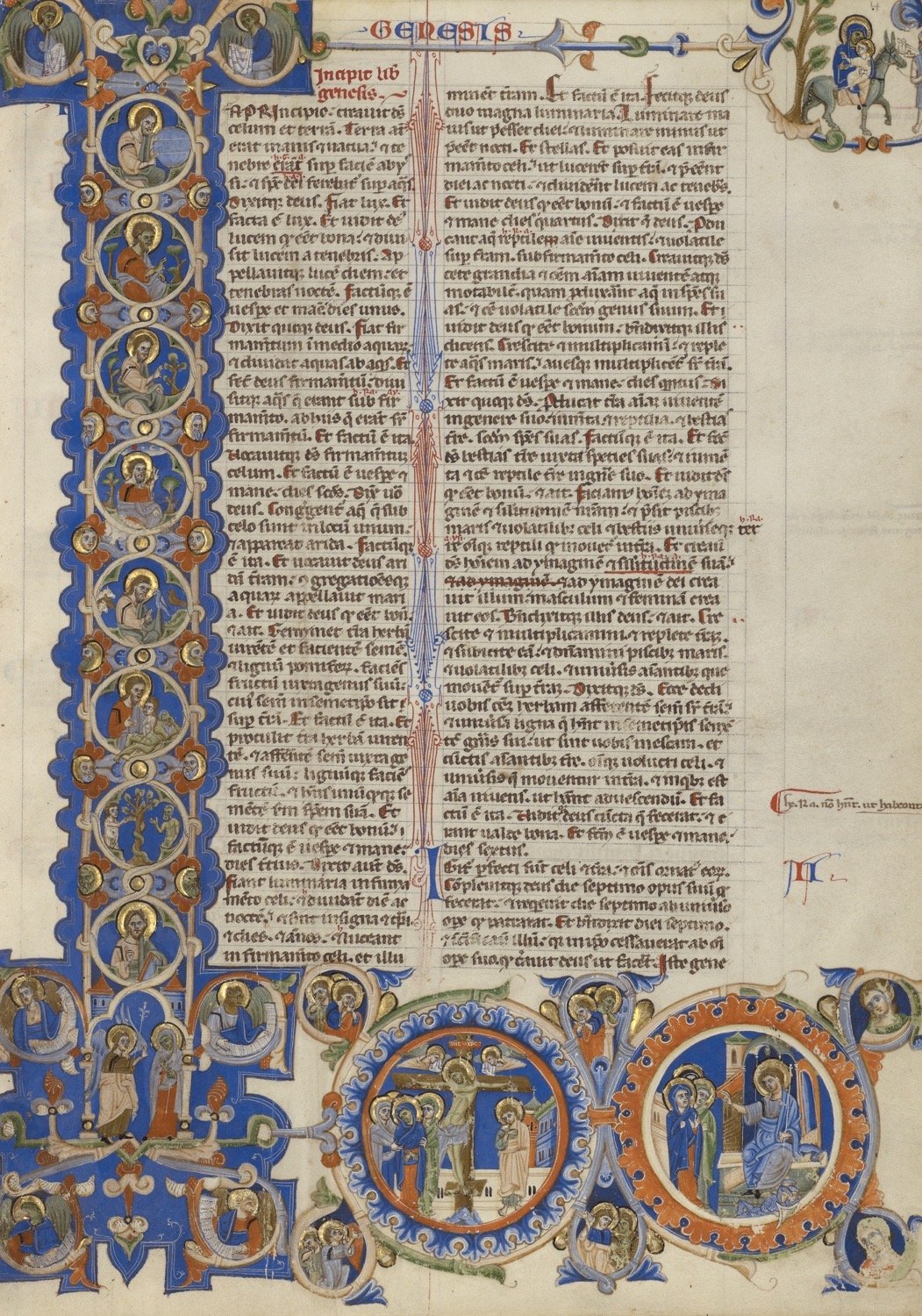

Images 2-3: Initial I: Scenes of the Creation of the World and the Life of Christ, about 1250-62, from Abbey Bible, Tempera and gold leaf on parchment, Leaf: 26.8 x 19.7 cm (10 9/16 x 7 3/4 in.), The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. 107

fol. 23 (2018.43.23)

fol. 3v (2011.23.3v)

fol. 4 (2011.23.4)

For example, in the top third of the page, under pointed arches, two animal heads on the ends of the snake-like necks of two fantastical winged beasts are intertwined, while two more animal heads on the ends of their two tails face the other direction behind them. Below a strip of gilded Hebrew letters and another colorful strip of plants and a rabbit intertwined with vines, a dog and a lion appear to be playing ball.

The inclusion of plants and animals in this and other Hebrew codices in the middle ages was a departure from the aniconic — without idols or images — tradition in Jewish culture. Prohibitions against images, which are found in the shared first five books of the Bible, led in some times and places to the prohibition of images of any kind, while in other eras only the creation of images to worship as idols was forbidden.

While Hebrew scrolls used for worship never had images, in many medieval manuscripts that were created for rich individuals for their personal study, images of all sorts were added to embellish the texts, probably in emulation of the Christian manuscripts of the era.

Especially interesting is that some say the images were painted by Christian artists, since Jews were excluded from artists’ guilds.

In the two facing pages on display from the Rothschild Pentateuch, human figures are not portrayed. On other pages, humanoid figures — some animals with the heads of humans, some animals with the lower bodies of humans and other animals eating humans whose legs are sticking out — appear, presumably to get around a lingering prohibition in place at the time against including images of humans.

Humans are depicted only on a single page — not shown — that was inserted one hundred years after the original manuscript was created, during the Renaissance.

Now let’s examine the differences in the Genesis illuminations in the Abbey Bible. In the two pages open from the Abbey Bible from the show, a monumental initial I runs vertically along the left margin of the right page. The red letters at the top of the letter I read “Incipit lib’ genesis,” “The beginning of the Book of Genesis.” The letter I is the first letter of the first words of the text: “In principio,” “In the beginning”.

In the vertical bar of the I and in its bottom bar, which extends across both pages, roundels contain narrative figures of humans and angels from the creation of the world and from the life of Christ. The images join the story of mankind’s original sin with the story of Christ’s Passion, death and resurrection, conveying the Christian belief that Jesus was the promised Messiah sent to redeem the world.

The image in the initial letter D on the left page is of St. Jerome — translator of the books of the Bible from their various languages into Latin — who is shown writing on a scroll. The text on that page is Jerome’s prologue to his translation of Genesis.

The only whimsical images in these two Abbey Bible pages run along the top of the left page. A blue-hooded head of a man seems to be blowing on a kind of trumpet, from which clouds emerge on the right of the page. A dragon bites into the top of the initial, and a dragon head is shown at the initial’s bottom.

Curator interview and commentary

In an email, I asked the Getty’s assistant curator of the show, Larisa Grollemond, to explain what the title “Painted Prophecy” means:

The title refers to the mode of interpretation that Christian devotees often employed in their reception and understanding of Hebrew scripture — illuminated manuscripts and the images within were important ways of visualizing the meaning of the Hebrew Bible (the “Old Testament” to Christian readers) in a Christian devotional context. So, the “prophecies” foretold in the Hebrew Bible were painted to enhance and make vivid the meaning and cultural/social importance of those events for a Christian audience.

Reading the beginning books of the Bible as prophetic was not unique to Christian devotees. God’s promises to send a redeemer to the Jewish people are in the Jewish Bible from the beginning. For example, in Genesis 3:15 — according to title, chapter and verse numbering introduced into the Christian Bible — immediately after cursing the serpent, God promises that Eve’s seed will be the enemy of the serpent and that a woman descended from Eve will crush the serpent’s head. This was seen by both Jews and Christians as a prophecy that a future offspring of Eve would restore humankind’s relationship to God and original state of innocence.

It is clear from much of the stories in the New Testament that the Jewish people — including the Virgin Mary, the men who became Christ’s apostles, the woman at the well, and even the revolutionary Barabbas — were waiting for the coming of the Messiah when Jesus came.

The major difference between the two religions about the prophecies in the Old Testament is actually that the Christian Gospels state and the church continually taught that Jesus is the Christ who fulfilled the prophecies of the Jewish Bible — which Jews who did not follow Jesus did not believe.

Even today, Orthodox and conservative Jews still hope for the arrival of the prophesied Messiah. Reformed and Reconstructionist Jews pray an ancient prayer for the coming of the Messiah, but for many, the hope is not for an individual Messiah but for the achievement of the Messianic kingdom of peace and justice.

I also wanted to know how the manuscripts, books and individual pages were chosen to be displayed in the exhibit. This was Grollemond’s response:

Most of the objects on view were drawn from the Getty’s permanent collection, and so were selected for thematic connection to the exhibition’s subject but also with attention to which images have not been displayed in the gallery for some time (or in some cases, ever displayed). The images chosen represent particularly powerful examples of both the Christian interpretation of the Hebrew Bible across Europe (and spanning several centuries of the Middle Ages), as well as the social reality of the antisemitic beliefs that many medieval Christians held about Jewish communities with which they interacted.

Elsewhere, the gallery notes state, “Many images in manuscripts reflect Christian prejudices against Judaism as a faith. ... They had a key role in the rise of violent and discriminatory acts against the Jewish people.”

As the earlier example I provided indicated, here in her answer, the curator seems to be using false evidence to support her point of view, since none of images chosen convincingly indicate “the social reality of the antisemitic beliefs that many medieval Christians held about Jewish communities with which they interacted.”

The commentary boldly implies that for Christians to merely believe that Jesus is the prophesied Messiah and to portray that belief in illustrations was evidence of antisemitism and symbolic of Christianity’s oppression of the Jews. It is a ridiculous claim that would be just as wrong if it was flipped, and if the curators were to claim that when Jews create images that indicate they don’t believe Christ is the Messiah they are oppressors of Christianity.

Admittedly, Jews have been hated and persecuted over the ages, but the images simply are not examples of antisemitism.

Regrettably, the commentary on the exhibit goes even further afield when it reads clues about misogyny into the illustrations of women in the show. Admittedly, women have been treated badly during the Middle Ages, and our age too, but the images in the Getty show are not examples of bad treatment or control of women’s behavior.

But again, space does not allow further specific examples.

I had one last question for the curator:

What would you say were the most important points of contrast you considered when curating this show? I mistakenly assumed that a juxtaposition of Jewish and Christian illuminations of the Torah/Old Testament would focus on their art historical aspects, especially since the prohibition against graven images in the second commandment had been interpreted so differently in the two religions. Your walkthrough, which I viewed online, obviously focused on other issues. So it would be interesting to learn more about your thoughts.

This was her response:

For me, the most interesting part of the conceptualization of the Hebrew Bible for medieval Christians is the contrast between the interpretation of that scripture in positive ways (the presentation of heroic figures from the Hebrew Bible as models for behavior) and the antisemitism that was widespread in medieval Europe and which deeply influenced the treatment of medieval Jewish people as well as the presentation of Jewish figures in manuscript illumination. Remembering that looking to the material past is complex, the manuscripts on display reveal quite a multifaceted, varied, and at times contradictory, view of shared scripture that existed alongside the fraught cultural and social realities of faith communities in the European Middle Ages.

Her wording, “The antisemitism … deeply influenced . . . the presentation of Jewish figures in manuscript illumination,” is another indication of the overall flawed interpretation that is apparent in the gallery texts. The wall text with the heading “The Jewish Presence in Medieval Europe” includes this line: “Many images in manuscripts reflect Christian prejudices against Judaism as a faith.” But the images actually reflect nothing more sinister than the fact that Christians believe Jesus is the Messiah and the Jews do not.

These quoted words from the curator again reinforce the distinct impression that the organizers of the show looked for evidence of antisemitism and misogyny because these are popular talking points in the culture of our time.

The images in the show’s venerable documents are captivating on their own without the addition of any glosses. The image from a psalter of David in the bottom of an initial S that shows him flanked by a devil and a dragon with his hands folded and looking up to Christ, flanked by angels in the top of an S, is a splendid example.

Go see the show if you can, or spend some time exploring the images at the Getty website, and enjoy.

R.T.M. Sullivan writes about sacred music, liturgy, art, literature and whatever strikes her Catholic imagination. She has published many essays, interviews, reviews and memoir pieces in print and online publications, such as Dappled Things Quarterly of Ideas, Art and Faith; Sacred Music Journal; Latin Mass Magazine; National Catholic Register; New Liturgical Movement, and Homiletic and Pastoral Review.