How A 13th Century Christian Monk's Ideas Of Virtue Offer Hope For Our Democracy

(OPINION) Polls show that a majority of Americans are very worried about the state of U.S. democracy. One survey from January 2022 finds that 64% of Americans believe U.S. democracy is “in crisis and at risk of failing.”

Both Republicans and Democrats affirm these concerns, but they have very different understandings of what exactly is in crisis and who is responsible. Most importantly, polls have repeatedly found that a majority of Republicans – tens of millions of Americans – continue to believe the lie that the 2020 election was stolen.

For those Americans who know that it was not, the entrenched commitment of their fellow Americans to a falsehood no doubt exacerbates their worries. How do you argue with someone who is committed to a lie? But the bigger question is what to do about it, given that so many Americans – myself included – fear for the very survival of our democracy.

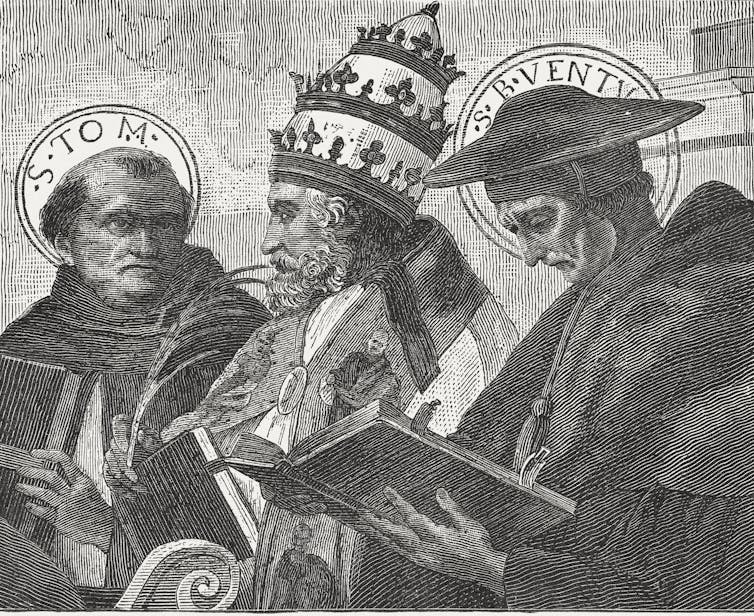

As a scholar who researches democratic virtues, I have spent time with the work of Thomas Aquinas, a Dominican monk who lived in the 13th century. Aquinas’ words are relevant to the times in which we find ourselves. Above all, he shows what it means to hope.

Hope as a theological virtue

Aquinas is widely regarded as the single most important Catholic theologian. His massive body of work speaks to virtually every aspect of the Christian faith. Most importantly, perhaps, Aquinas insisted that reason and revelation were separate but complimentary forms of knowledge. He argued that since both ultimately come from God, they cannot be in conflict.

Accordingly, Aquinas is also one of the first thinkers to reconcile the work of ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle with Christianity. Aristotle argued that ethics is principally concerned with becoming the best version of ourselves. For Aristotle, a truly ethical person is also a truly excellent person.

Aquinas accepted this understanding. But he also argued that Aristotle’s interpretation of ethics was incomplete and imperfect. Aquinas said that ethics must also incorporate the theological virtues of faith, hope and charity. These virtues, Aquinas argued, come to us not from reason but from grace. They are gifts from God that serve to direct people toward their salvation. According to the theologian, they make it possible for human beings to achieve a dimension of both happiness and excellence that they cannot achieve otherwise.

Aristotle defined virtue as “a mean between two vices, that which depends on excess and that which depends on defect.” So, for example, Aristotle said that courage is found between recklessness – an excess of courage – on the one hand and cowardice, its deficiency, on the other.

Deciding how to be courageous is never simple and depends dramatically on circumstances, but courage will always be found between these extremes. Aquinas follows this concept of virtue, and he argues that the theological virtue of hope fits the pattern. According to him, it lies between two vices: Presumption is the excess of hope, while despair is its deficiency.

Presumption is the easy confidence that everything is going to be fine. The presumptive person thinks that no matter how much he sins, as Aquinas notes, “God would not punish him or exclude him from glory.”

Despair is the opposite. It means the sinner believes that she has fallen so far from God that she has no possibility of salvation.

The question of salvation is one thing, while the condition of American democracy is entirely another. Nevertheless, there are examples of many Americans responding to the current democratic crisis with the same vices of presumption and despair.

Democratic presumption and despair

In the current democratic crisis, presumption appears as a vague optimism that American democracy has survived many crises and that this is just another one. Many Americans believe that the current crisis is a problem for those in power to address; whistling past the graveyard, they see no reason to change their own behavior.

Political scientist Sam Rosenfeld notes that despite a prevailing feeling of crisis, “voting behavior has not changed in response; it’s shown remarkable stability and continuity with patterns established at the outset of the century.”

Despair is even more apparent. Most Americans have expressed at least temporary feelings of despair around climate change and a seemingly never-ending pandemic, and also about our democracy.

And no doubt having all of these crises coincide at once only adds to the sense that they are beyond our ability to solve. But for Aquinas, hope is not merely the mean between these two vices; it is also the more realistic response to our condition.

Hope as a democratic virtue

By Aquinas’ definition, hope is grounded in some desired future that is both possible to achieve but also very difficult. Hope is therefore more realistic than either vice.

Presumption denies the difficulty of the goal, but also the responsibility of the individual in making it happen, while despair denies the fact that the goal, despite its arduousness, is yet possible. Hope is the mean because it requires people to be both clear and conscientious about what they are up against, and what they are striving to achieve.

In this understanding, hope is much more than mere optimism. Hope is an act of will. One chooses to be hopeful. Hope insists that though the task is difficult, even daunting, change remains possible. It therefore sustains all who take up the work that must be done.

If this act of will seems beyond your ability right now, consider this. Aquinas said that “we hope chiefly in our friends.” It is easier to be hopeful when others love us, support us, and share our hopes. This is why, he says, Christians need a community of fellow believers.

[Over 140,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today.]

For Americans faced with the current democratic crisis, community can include anybody who is likewise ready to embrace the hope that American democracy can endure. That community, as well, is better able to overcome the inclination to despair, and more able to achieve the desired outcome.

Understood the way Aquinas suggests, hope emerges as a distinctively democratic virtue. Without willful, realistic hope, and without a coalition of hopeful people working together, Jim Crow does not end, the Berlin Wall does not fall and marriage for gay couples remains impossible.

That history, as well, ought to inspire us to find the hope we need right now.![]()

Christopher Beem, Managing Director of the McCourtney Institute of Democracy, Co-host of Democracy Works Podcast, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.