How the oldest surviving Latin Bible was scribed in England

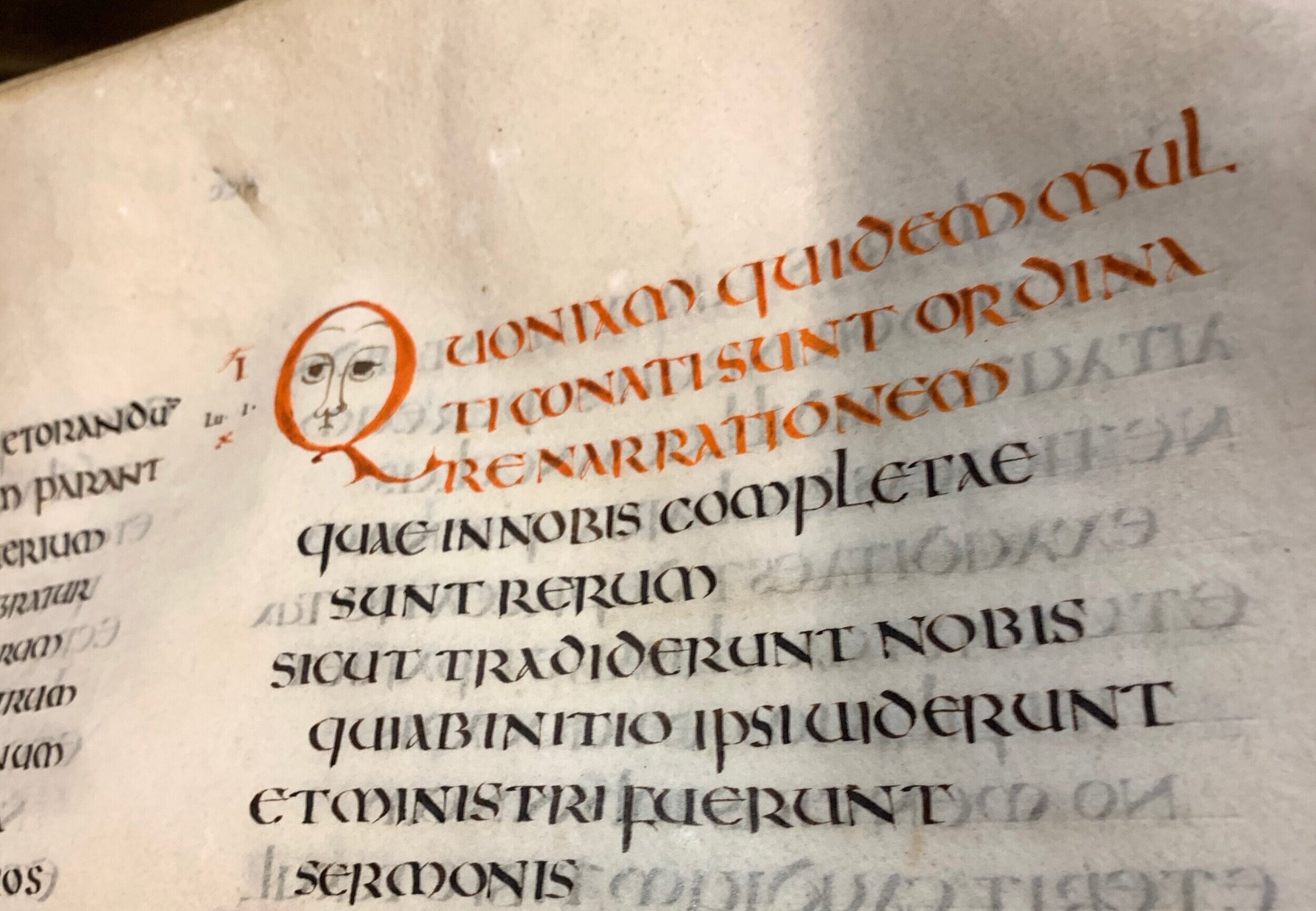

A page from the Codex Amiatinus. Photo by Roberta Ahmanson.

(TRAVEL) It was just a side trip to Newcastle with old friends. For once I had no agenda. I was going along for the ride. My husband, Howard, wanted to see Newcastle because no one ever goes there. Of course, why else would one want to go anywhere? And, our friends, Brits, agreed.

Well, there happens to be a lot to see and do around Newcastle, including one of the best restaurants I’ve been to in my life – it’s called The House of Tides, right downtown.

But, maybe more important, a piece of history was about to connect parts of our trip in an unexpected way. Little did I know that Howard’s longing to go to Newcastle would take us on a journey back in time that would lead us to a very old book created in the North but now found in Florence, a place we were planning to visit but for very different reasons.

Back in Newcastle, the unexpected pilgrimage began. On our first day, the four of us took the metro into the city and noticed that it went to a place called Jarrow. Well, somehow my husband and I both knew that the Venerable Bede (673-735), the English Benedictine monk also known as Saint Bede, had lived at a monastery there where he wrote his many books. (Foremost among them The Ecclesiastical History of the English People.) Was anything still there? Did our friends want to go?

Well, yes, there most certainly is something there. And, no, our friends did not want to go. So, we saved that stop for the day they went home to the south, and we headed north to the Edinburgh Festival.

The day after we explored Newcastle itself, our friends took us to a town that dated to the time of the Bede. Hexham, 30 miles north of the city, boasted a church and monastery founded in the 7th Century by St. Wilfrid, who was bishop of York in the Bede’s lifetime. At one point Hexham even had a bishop. Wilfrid’s church and monastery are long gone. But, the crypt is there. And, down we went.

The parish church of St. Andrew in Hexham. Photo by Roberta Ahmanson.

The Anglo-Saxons had cobbled stones from the nearby Roman city of Corbridge. So you see Roman carving and even a grave monument that now stands upstairs in the church. My interest in these Anglo-Saxons was piqued. There was more to come.

The day we parted from our friends and headed to Jarrow, we saw a sign that said: Bede Industrial Park. We knew we were in the right place, but we wondered if Bede thought writing histories would land his name on future economic development sites.

It was raining. Not fierce sheets, but that steady kind of thick rain, soft but serious, the kind that seems to land on trees and then ooze gently onto whatever is below. Umbrella time. We got to Jarrow.

A typical Anglo-Saxon farm maintained at the Bede Museum in Jarrow, England. Photo by Roberta Ahmanson.

We found, first, a replica Anglo-Saxon village complete with free-range chickens and roosters who didn’t seem to be bothered by a little rain. You could smell the earth musk, that great rain fragrance. We made passing acquaintance with a cow or bull, not sure which, and headed for the Bede Museum. That was where the revelation began.

We learned that in 653, a 25-year-old Northumbrian nobleman named Biscop Banducing had gotten it into his head to go to Rome. He gave up his place as a thegn (a highly regarded nobleman and attendant) of the king of Berenicia, the northern part of what is now Northumbria. He went with the Wilfrid we had already met in Hexham. Biscop came home with ideas for making the Anglo-Saxon church more like the church in Rome.

The altar at the parish church of St. Andrew in Hexham. Photo by Roberta Ahmanson.

What was there to transform? Well, Christianity had come north with the Romans as early as the 4th Century. It was St. Patrick who took the faith to Ireland, where it spawned a flourishing monastic movement. Meanwhile, Roman Christianity in Britain was being displaced by Anglo-Saxon paganism. In the 560s, an Irish monk named Columba was sent to Britain where he founded the monastery of Iona in the Irish style. In 597, Pope Gregory the Great sent Augustine to Britain to either revive or introduce the Roman Christian tradition. He was the first Archbishop of Canterbury.

What does that have to do with Bede and Biscop? Background: In 616, yet another Northumbrian nobleman had been exiled to Iona. This Oswald became a Christian there. When he became king in 634, he sent for a monk to start a monastery in his kingdom, and that became the monastery at Lindisfarne, where scribes created the Lindisfarne Gospels in the Irish insular style in the early 8th Century.

Biscop, born in 628, had grown up around Irish Christianity, which was very different in style from what he saw in Rome. And, from his first visit on, it was Rome he wanted to bring north. Twelve years after his first – of five trips total – Biscop went back to Rome largely on a book-buying trip. From Rome, he stopped at the then-famous monastery at Lerins, near what is now Cannes. Back then, the French Riviera was known more for monks than movies. There, Biscop took the vows, the Roman tonsure (a bald top surrounded by a crown of hair), and the name Benedict to become a monk. After two years, in 669, Pope Vitalian sent him back to Britain with the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Theodore of Tarsus, and a monk named Hadrian.

After a later visit to the Continent to hire stone masons and glassmakers, he founded first St. Peter’s monastery in Wearmouth in 674-75. On a fourth visit to Rome, Benedict took his assistant Ceolfrith and the pair convinced Pope Agatho’s cantor John to come to Britain to teach liturgy and song. On their return in 684-85, Benedict established St. Paul’s in Jarrow with Ceolfrith as abbot. A revolution had begun.

“Not only did John instruct the brothers in this monastery, but all who had any skill in singing flocked in from almost all the monasteries in the kingdom to hear him, and he had many invitations to teach elsewhere,” Bede wrote in the Ecclesiastical History.

But what was this revolution? Well, Irish monasteries were made of wood. No icons. No frills. No singing like that in Rome. Benedict, in contrast, brought stonemasons and glassmakers from France to build monasteries of stone with colored glass in the windows. With each trip south came more books – in total he brought some 250 manuscripts – including Greek and Roman classics as well as Scripture and commentaries. He also brought icons and fabrics and metalwork. A revolution indeed. Visual and liturgical.

Before one of his trips to Rome, Benedict combined the two monasteries as one entity and made Ceolfrith abbot of the joint monastery of St. Paul’s, Jarrow, and St. Peter’s, Wearmouth. It was probably to Wearmouth where the man who became the Venerable Bede (673-735) was taken to be educated at the age of seven. He became a deacon at 19, a priest at 30. Biscop and Ceolfrith were his mentors.

Inside St. Paul’s church in Jarrow. Photo by Roberta Ahmanson.

It’s likely Bede went to Jarrow with Ceolfrith when it was founded, though we can’t be certain. (One piece of evidence, however, is that his bones were found there in the 11th Century when the monastery was revived and then taken to the cathedral in Durham, where they are to this day.)

Monasteries on the Continent housed scriptoria where monks worked daily to produce copies of books, and the Northumbrians wanted to do the same. That’s where the connection to our trip comes in.

In 689-90, Biscop took Ceolfrith to Rome once again. This time Ceolfrith came back with what is called a pandect – a single volume of Jerome’s Latin translation of the Bible, known as the Vulgate – and a dream. This Bible may have been a copy of the Codex Grandior – a 6th Century Bible made for the great statesman-scholar Cassiodorus who, after serving as secretary to the Ostrogoth King Theodoric in Ravenna, went south to found a study center and library in Calabria.

From books like these, the monks of Jarrow and Wearmouth learned the elegant uncial script perfected in Rome to use in their own manuscripts. This was very different from the insular (so named because it was developed on the Irish island) script used at Lindisfarne. The monks also learned the technology of making books. So, by the 690s they were ready for a massive project. And Ceolfrith was a big step closer to realizing his dream.

In 692, the monasteries received a grant to raise 2,000 head of cattle whose hides were needed to produce the vellum for such a project. Over the next 20 years, 515 hides were used to complete three copies of the Latin Bible. Bede may well have worked on them or at least worked with those who did.

Two were meant for the monasteries. The third was for Pope Gregory II. In June 716, Ceolfrith left for Rome to make the delivery. He got as far as Langres in France, where he died Sept. 29. There the copy stayed.

From there the clouds roll in. The next mention comes from the Abbey of the Savior – Abbazia San Salvatore – on Mount Amiata in Tuscany where it is listed among the abbey’s relics in 1036. In 1782 or 86 (different sources give different dates), the monastery was closed, and the manuscript was taken to the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence, where it remains. For a time, due to alterations in the dedication page, scholars thought the codex was produced at St. Benedict’s monastery at Monte Cassino in the 540s. But, German scholars noticed similarities to 9th Century Northern texts. In 1888, Giovanni Battista Rossi established that it was related to Bibles mentioned by the Venerable Bede.

As a lover of mysteries, this was right up my alley. Then came the aha! moment. We were going to be in Florence in two weeks. We could actually see this manuscript. I emailed Timothy Verdon, a friend and director of the Museo del Duomo. He graciously arranged a visit.

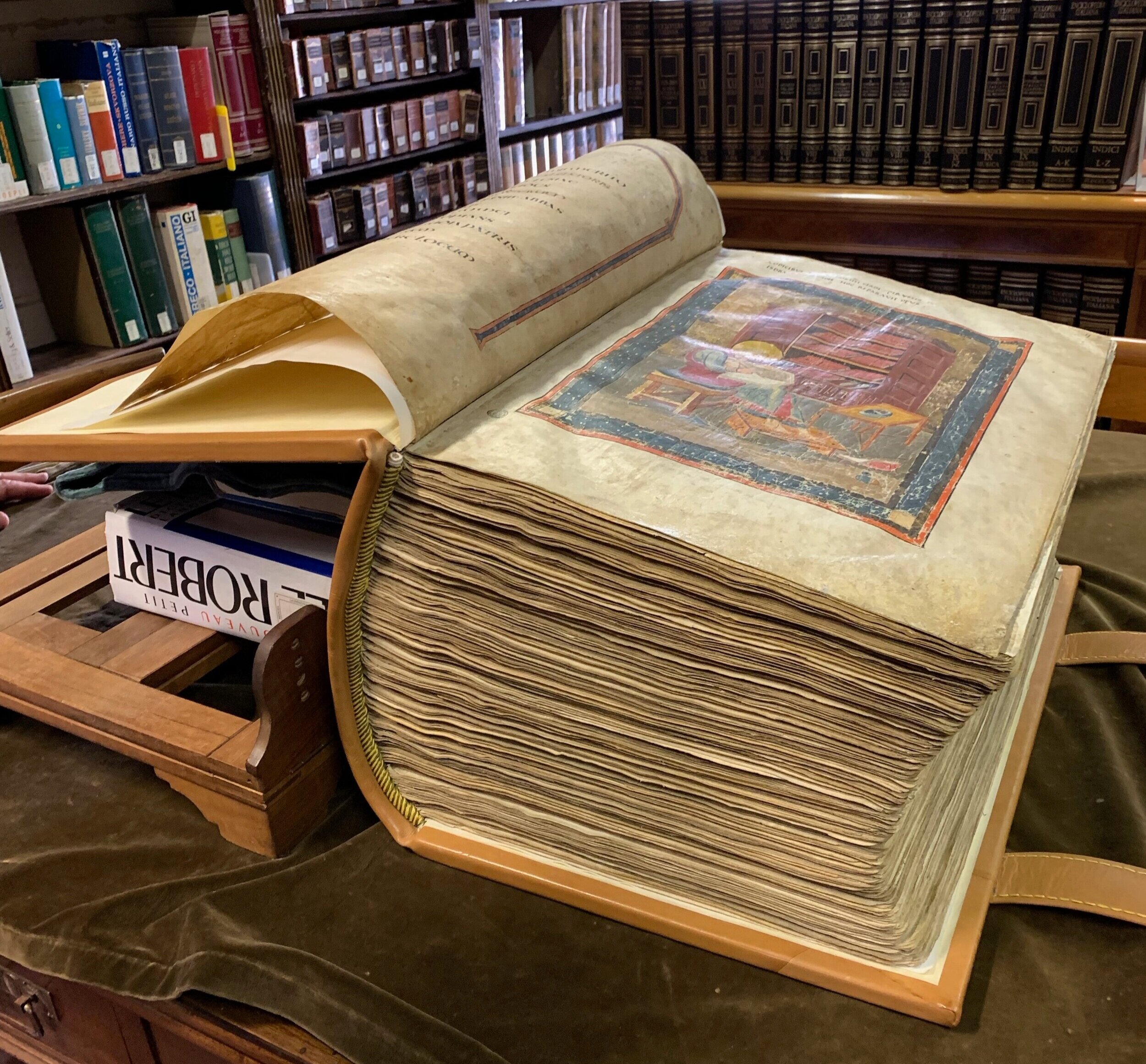

So, at 10 on Thursday morning, Sept. 5, Timothy, Howard, and I met at the Biblioteca, walked up the stairs, passed a room designed by Michelangelo, and stepped into a more utilitarian room where a huge book lay open on a table.

Tears actually came to my eyes. There it was, the Codex Amiatinus, the oldest extant text of the Latin Bible, produced 1,300 years ago in a damp stone building in Northumbria by monks whose monastery would be abandoned not 100 years after their achievement. (Lindisfarne, just 60 miles away, was sacked by Vikings in 793. Wearmouth and Jarrow were attacked and abandoned by 800.)

The ruins of St. Paul's Monastery in Jarrow. Photo by Roberta Ahmanson.

For a moment, I was back in Jarrow on that rainy day three weeks earlier. St. Paul’s Church is still there. As are the ruins of the monastery, across a park from the Anglo-Saxon village and the museum. Today the original church, the one Benedict Biscop dedicated in 684-85, is the chancel of a larger building. Carved wooden benches had fanciful images of monks, one with his tongue sticking out. The rain provided music. The muted light shown through windows remade from fragments of Benedict’s colored glass found on the site.

I stood there imagining Bede and Biscop and Ceolfrith. And Bede.

The Codex Amiatinus as seen in Florence at the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana. Photo by Roberta Ahmanson.

Living men. Men dedicated to the Gospel and to learning. Men who believed in the Glory of God and its witness in the works of men and women and gave their lives to spreading that light.

A blink and I was back in Florence. There on a table, in a room built by the Medici, was evidence of that Northern labor and Ceolfrith’s dream.

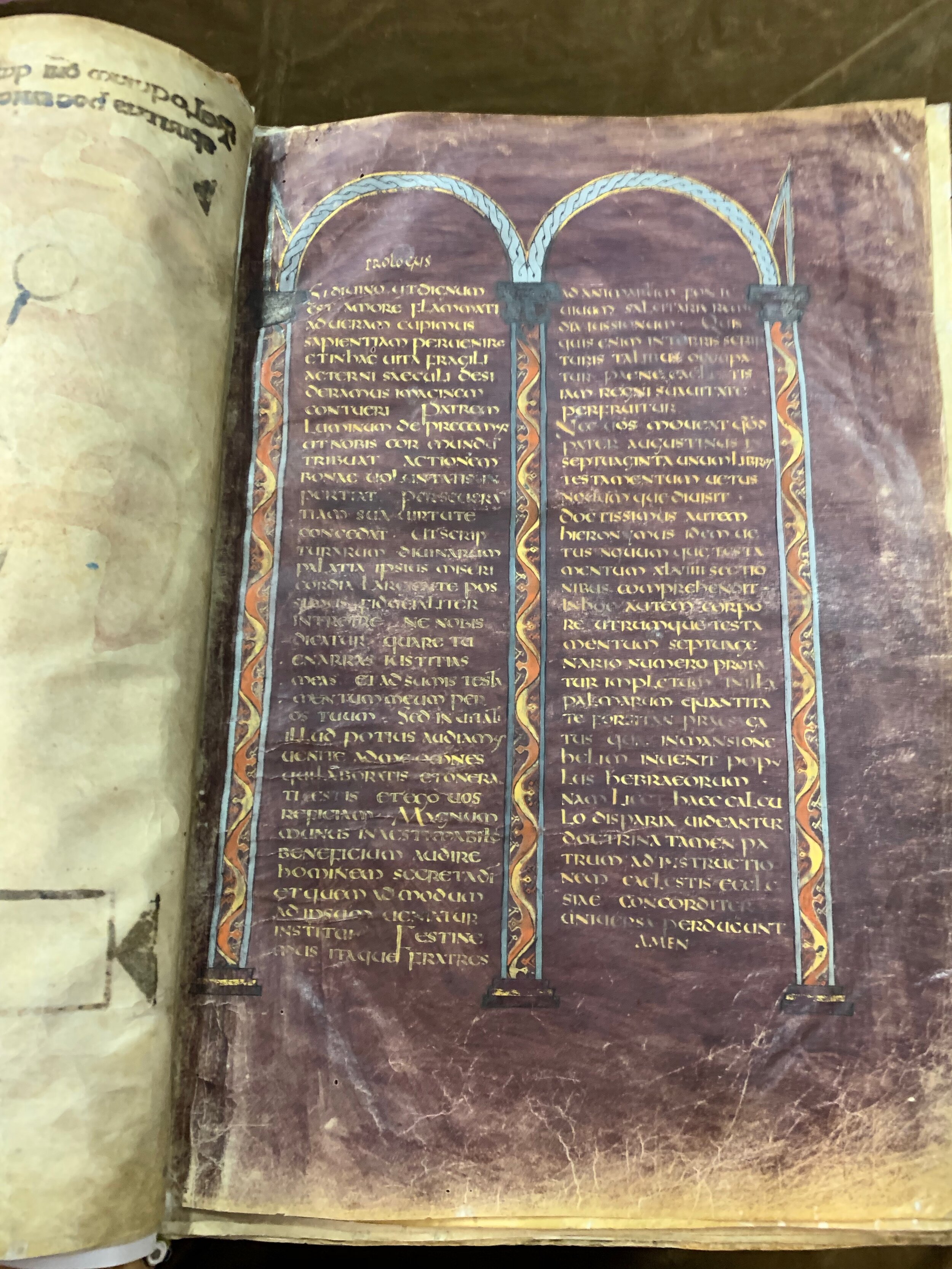

A purple page from the Codex Amiatinus with gold script, a luxury usually used for Roman emperors. Photo by Roberta Ahmanson.

It is a Roman, not an Irish, book. The calligraphy is Latin in form, perfectly regular. The images use shading and color in the Roman way. The text opens with a full-color image of the Scribe Ezra in his study working away. An image of the monks of Jarrow?

There is a preface in gold ink on purple paper – a luxury reserved for only the most important texts, usually for emperors. There are diagrams of the Testaments based on the work of Jerome and Augustine.

Each book opens with a synopsis of the chapters. A triumphant Christ in Glory with the Four Gospel Writers divides the Old from the New Testament.

What makes this big book so important? For one, scholars agree it is the text closest to Jerome’s Latin translation as it was most likely done from a manuscript brought directly from Rome by Benedict. As such, it was the principal text that shaped the Roman Catholic Church for more than 1,000 years. And, it remains the basis of the Bible for the worldwide church.

Further, the Codex Amiatinus connects today directly with the earliest translation of the Bible from the original Greek and Hebrew. That alone is important to anyone studying a text that has shaped the Western World and now is a text shaping the growing Christian Church in Asia and Africa. For Christian believers, the Codex Amiatinus is a direct connection to the faithful across time.

Auspicious, the codex is. But, it is human too. One chapter opens with a round red letter circling a face winking out at the reader. The very last words in the text are written as a diagram. They say: “Pray for me.”

And, we, as no doubt many others before us, did.

Roberta Ahmanson is a philanthropist, art collector and writer who started her career as a religion reporter at the San Bernadino Sun and Orange County Register. She is the co-author of Islam at the Crossroads and Blind Spot: When Journalists Don’t Get Religion. She is also the chairperson of The Media Project’s Board of Directors.