Christianity continues declining in the US: Pew Research

A man passes an offering plate at a Baptist church in North Texas. Photo by Meagan Clark.

NEW YORK — The decline of Christianity in the U.S. is continuing at a “rapid pace,” according to the latest Pew Religion research released Oct. 17.

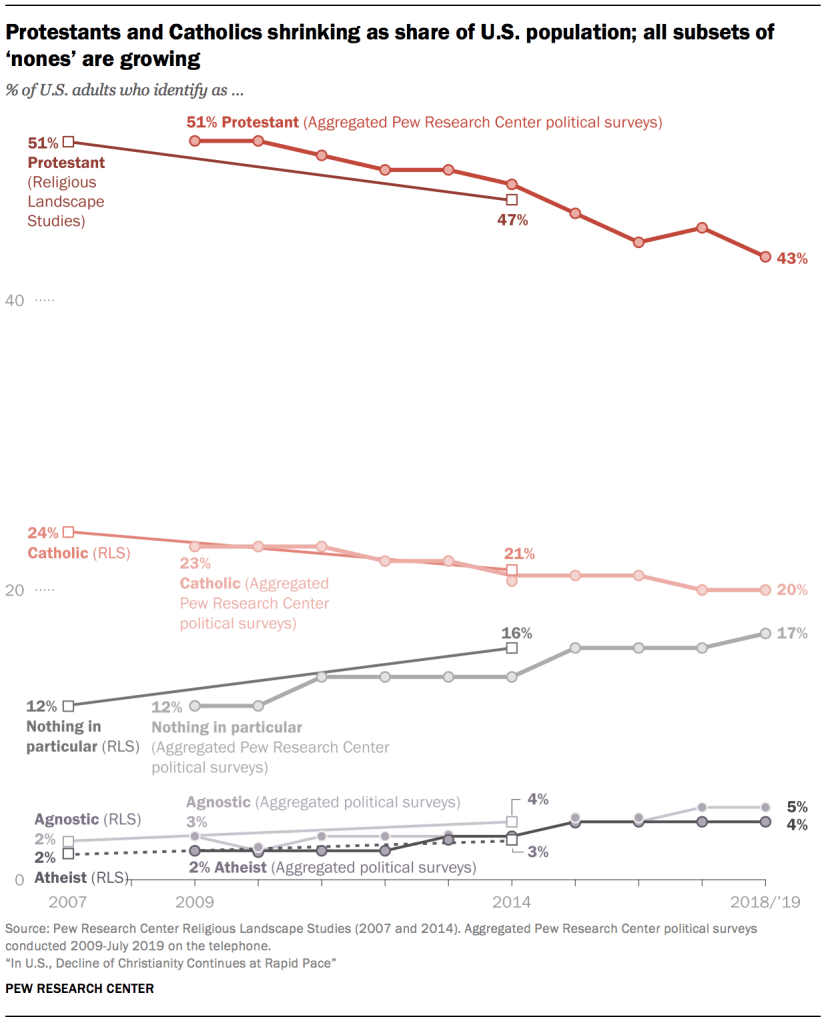

Fewer Americans than ever before are attending church and fewer are self-identifying as Christians. According to phone surveys in 2018 and 2019, 65% of American adults describe themselves as Christians, a steady decrease from 77% a decade ago. The so-called “nones,” or people who aren’t affiliated with a faith, are increasing. Now 26% of Americans describe themselves as atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular, an increase from 17% in 2009.

“People active in religious organizations are more likely to donate to organizations and volunteer (even non-religious ones) and more likely to be involved in civic society,” said Alan Cooperman, director of religion research at the Pew Research Center. “So one concern is less involvement in civic society.”

Members of non-Christian religions like Islam and Hindusim have grown modestly, mostly due to immigration, while both Protestant and Catholic churches are seeing declines in the U.S. The Catholic church in particular would see more decline if not for Latino immigration, according to Gregory Smith, associate director of research at Pew. When asked in September at an event by the Faith Angle Forum, Smith did not know of any denomination in the U.S. that has grown over the past decade.

Rates of religious attendance, as separate from affiliation, are also declining as the number of Christians shrinks. Those who identify as Christian are attending church as often as Christians did in 2009.

While “nones” are growing faster among Republicans than Democrats, their growth cuts across race, gender, education and region. Their growth is most pronounced among young adults (Millennials), while 84% of older Americans born between 1928 and 1945 and 76% of Baby Boomers identify as Christian. Only 49% of Millennials now describe themselves as Christian, while 10% identify with other religions and 40% are “nones.” Although more women identify as religious than men, the number of women identifying as “nones” is increasing.

But the category “nones” can be confusing. People who identify with the term may still attend church or seek religious rituals or meaningful conversation around spirituality but not want to call themselves “religious.” At a Religion News Association gathering of religion journalists in September, researchers and writers discussed Millennial spirituality and trends, concluding the drop-off in church attendance is probably due to increasing mistrust of institutions.

“I think there’s a desire for community, but I’m not so sure there’s a desire for authority,” Paul Raushenbush, a senior advisor for Interfaith Youth Core, said. “What it means to be human has been undermined by the Internet. Who is our community? Who are our authorities? There is less interest in authority now than in past generations.”

Partisan politics may be partly to blame if young people associate some Christians like evangelicals with the Republican Party and morality around sexuality, but liberal Protestant churches are also losing members. There is also no evidence that more Americans are describing themselves as spiritual or abiding by their own sets of personal beliefs.

Not everyone is pessimistic though. Some pastors, like Joey Furjanic of The Block Church in Philadelphia, a non-denominational church, say they bring in thousands of Millennial “nones,” and not just through live streaming services online. He pushes back on the idea that young people dislike authority, saying everyone wants to be led.

“We have nearly 2,000 people, mostly Millennials who used to go to church and are now coming back,” he said. “I think it’s important to illuminate that the church is dying, but there is also absolutely a revival of the church in Jesus.”