An Irish Craftsman's Work Comes to Life in The Windows Of NJ's St. Vincent de Paul Church

Saint Vincent De Paul Church in Bayonne, N.J. Photo by Paul Glader.

BAYONNE, N.J. — Peter Keenen O’Brien walks into the church he’s known since childhood listening to the organ music, feeling reverence in the expansive space and staring into the stained glass windows that depict, among other scenes, the death, burial and resurrection of Jesus.

O’Brien’s father, grandfather and great-grandfather have run the funeral home across the street — Avenue C — from Saint Vincent De Paul Roman Catholic Church since 1891.

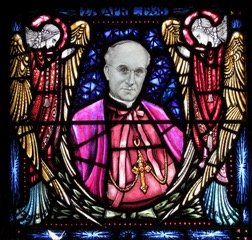

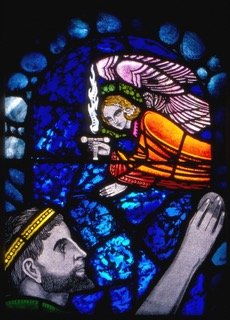

Image of Harry Clarke of Dublin

“The architecture of the church reflects the theology of what you believe,” O’Brien said as he explains the details of the Algerian onyx used on railings and other features around the altar.

READ: 5 Things You Didn't Know About The Feast Of St. Patrick

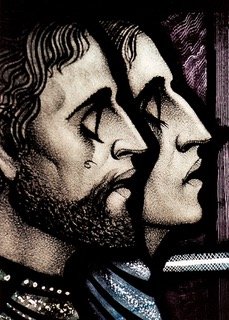

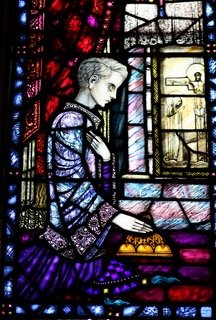

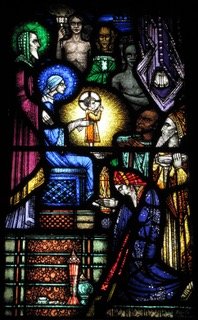

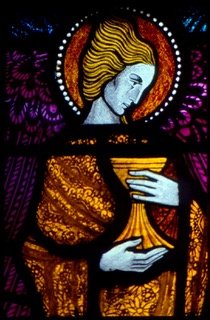

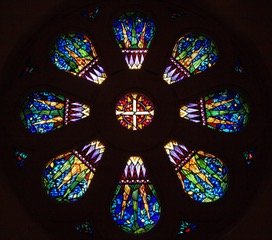

Yet the windows keep drawing your eyes to study the images. The telling, minute elements — lines in a beard, expressions on faces — are detailed in ways that make other stained glass windows seem dull. The color palate is more brilliant - like an LED screen from the 2000s rather than the picture tube technology from the 1980s. Instead of pastel colors found in other stained glass works, these hold bold, rich jewel tones.

The master craftsman who developed these windows a century ago, Harry Clarke of Dublin, synchronized a recurring theme throughout the 40 panels: Sacrifice.

Wearing a dark suit and seeing dark SUV hearses pull away from the church earlier that day, O’Brien sees death, suffering and sacrifice regularly in the funeral business.

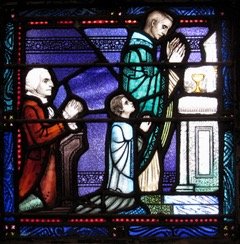

“Each of the panels in the nave has an Old Testament figure or story paralleled with a New Testament story,” O’Brien said. “The Old Testament images are all the different occurrences of sacrifice. And then… they found scripture passages that match the New Testament, and a priest or bishop saying mass. The sacrifice from the Hebrew Scriptures now becomes the Sacrifice of the Mass in the Christian scriptures.”

Among the tourists who have visited the church to see the windows, a young rabbi brought his congregation to see the marvelous depictions of Hebrew figures.

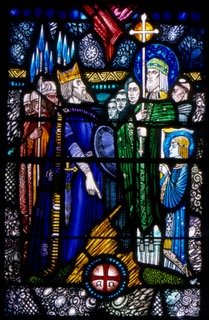

Finding Saint Patrick

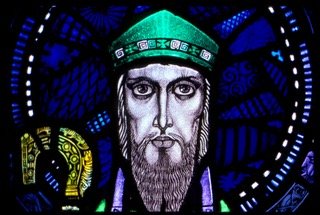

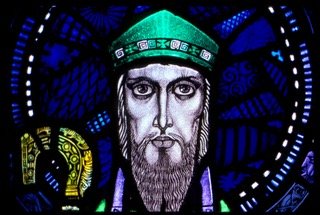

Saint Patrick of Ireland wearing his emerald miter.

We find the image of Saint Patrick of Ireland staring back at us with a knowing gaze, his facial features and beard depicted in grey find a symmetry within the deep blue patterns of the window. An emerald crown gleams from atop his head.

Patrick, according to history, was captured at the turn of the 5th Century by a group of Irish pirates when he was 16 years old. He was taken from Great Britain and held as a slave in Ireland for six years. His Christian faith grew in captivity to the point some of his captors became Christians and Patrick later returned to Great Britain.

Patrick is said to have returned to Ireland as a Christian missionary, baptizing thousands of people, ordaining priests and leading many in the landed gentry and rulers toward faith. His adult life included ups and downs and additional suffering for his faith.

Patrick is recognized as the patron saint of Ireland and sometimes called the “Apostle of Ireland.” His death on March 17 is a public holiday in Ireland and many other places. The United States is known to host parades, ceremonies and plenty of alcohol consumption on the holiday, celebrated in cities across the country.

Working Class Wonder

The touches of green throughout the Clarke windows remind us this church was built by Irish immigrants like Mr. O’Brien’s ancestors back when Bayonne was a hub of oil refineries such as Standard Oil of New Jersey near the end of the 19th Century.

The window designs include some nautical imagery and sea creatures and shells that pay homage to Bayonne’s geography as a peninsula on the Hudson River near the Atlantic Ocean. The New York Times, in a 2000 article, noted the regional history contained in the windows: “The 40 panels include a depiction of George Washington praying in Morristown and a priest traveling by sleigh to visit Roman Catholics throughout northern New Jersey.”

By 1913, a young priest named Joseph Dolan became pastor of St. Vincent de Paul in Bayonne. Dolan was a geek about art, beauty and architecture. He had tracked the art and architecture in Italy and dreamed of incorporating such work into a church of his own one day.

Catholic churches dotted the landscape in Bayonne with Germans, Slovaks, Ukrainians, Poles and Irish all desiring their own parishes. Bayonne had eight Catholic churches within 2.5 miles. And St. Vincent’s was an Irish part of that ethnic mosaic. But it diversified and included others over time.

“In the beginning, it was Irish. And then we had a large Italian population. There was a falling out with one of the Italian pastors many, many years ago. And Father Dolan, who built this church, studied in Italy, was ordained in Genoa spoke fluent Italian. So he welcomed them up here,” O’Brien said in an interview with ReligionUnplugged.com. “So since I was growing up in the late late 50s, early 60s, there was always nice Italian and Irish mix, some Polish recently. The immigrants we have now are largely Filipino and Central, South American.”

When Dolan became leader of St. Vincent’s, he realized the congregation needed a new building as it had outgrown its space. So he hired the architectural firm McGinnis & Walsh, which also built all or parts of famous cathedrals in New York and Washington D.C.

The working class immigrant families paid for the windows and the church building with tithes and donations from their hard-earned money as laborers in the oil refineries. Their church was their place of spiritual transcendence, education, support and community throughout the week.

Dolan knew “nobody except Harry Clark will put the windows in” the church. Clark was born on St. Patrick’s Day in 1889. He’d illustrated books by Hans Christian Andersen and Edgar Allen Poe. He designed fabrics before he joined the family business of decorating churches.

Though he died early at the age of 41, smitten by Tuberculosis, Clarke left a legacy as a leader in the Irish Arts and Crafts Movements. And, after he died, his wife Margaret Crilley Clarke and the stained glass artist Richard King followed the instructions Harry Clarke left and finished the project by 1944. St. Vincent's in Bayonne is the only church in the U.S. that has windows designed by Clarke, now regarded as a master in the artistic medium.

“It was his glorious imagination… that really put Clarke’s work literally on another level,” Lucy Costigan, a scholar on Clarke, told JerseyCatholic.org. She ranks his work alongside masters such as Tiffany, Burne-Jones and Matisse. "His natural ability to depict scenes, to design robes, and to add tiny details made his windows come to life in a way that other works did not.”

Recovering the History

To some degree and for a period of time, the congregation and the archdiocese didn’t fully realize or celebrate the history and quality of the artwork in its own midst.

Priscilla Ege attends St. Vincent’s each week for an evening mass, joining the parish 25 years ago after the Slovak church she grew up in closed in Bayonne.

“I look at the windows” every week, Ege told ReligionUnplugged.com, about her continued awe at the masterpieces in the house of worship she attends. “It doesn’t get old.”

Ege is a town historian in Bayonne and involved with local historic and preservation committees. She and O’Brien found some documents explaining the windows in 2007 in the building and began pursuing state and national historic designations for St. Vincent’s. After painstaking paperwork and applications, the church attained such designations in 2011.

Preserving History

It was “an appreciation for what we have” that drove parish members like Priscilla Ege to document and celebrate the Harry Clarke windows.

It was “a labor of love,” O’Brien said.

It was “an appreciation for what we have,” Ege said.

Ege and O’Brien wrote booklets and resources documenting facts and features about the windows. They explain, for example, how the artist crafted 14 clerestory windows the depict the Passion of Christ. They explain how Clarke used techniques to create lines and shades so that clothing in the windows take on a realistic folds and shapes. Other techniques allowed for detailed and emotional face expressions with haunting eyes and stylized hair, resembling images in a painting, illustration or photograph.

A New Era

Bayonne has changed over time. Its row houses and streetscape still carry a blue-collar, working class feel. Its oil refineries have disappeared. Now, more of its people commute across the river to New York City for work. A movie production facility called Studio 1888 is under construction at the south end of town. “That will be a big employer,” O’Brien said.

O’Brien and Ege sometimes host walking tours and presentations with community groups, tourists and even groups from cruise ships to share the history and beauty of Clarke’s windows and St. Vincent.

Some people, “before they board their cruises, have come ringing the doorbell, ‘Can we take a look?’… If I'm not working or Priscilla's not working, we can come by and let them in and show them around.”

The church hopes to refurbish the windows, which are starting to warp in some places because of heat. O’Brien and Ege believe a vented glass frame system would help protect the windows better, a project that could cost $150,000 or more.

One architect who visited the church said ”it's like a well preserved Faberge egg,” O’Brien told ReligionUnplugged.com “And we're constantly trying to keep up with the building. It's almost 100 years old, so it's hard, but we take pride in it.”

A school connected to St. Vincent is closed up, its own windows broken in places. Father Dolan is buried in the yard in front of the church, always remembered by the parish.

“He had great taste,” Ege said of Father Dolan. “We are very lucky. He developed a building that is a magnificent church.”

Some of the Catholic Churches in Bayonne have merged over the years. The Slovak church St. Joseph’s church and the Lithuanian church called St. Michael’s closed and consolidated with a Polish parish called Mt. Carmel. Other Irish churches combined with larger parishes in Bayonne.

Now at St. Vincent’s — one of 212 parishes in the Archdiocese of Newark — the largest percentages of parishioners include Filipinos, Hispanics and Irish. The pastor of the parish, Father Sergio Nadres, is of Filipino heritage himself.

“We're definitely not Irish anymore, but very welcoming to the Filipino and the Hispanic community that are here,” O’Brien told ReligionUnplugged.com. He said some parishioners from other places enjoy their own special masses and religious observances of saints and events particular to their cultures and contexts.

Some protestants and other faith traditions in America sometimes disdain the money and effort spent on craftsmanship and artwork in churches like this one in Bayonne. O’Brien notes that he’s grateful that Father Dolan, the architects had a fine artistic sense and that hardworking parishioners were willing to fund their effort to obtain marble, stained glass, wood and other fine materials from around the world.

And there were spiritual reasons for this quest. It wasn’t just about pride. It was also about sacrifice. And their sacrifice contributed to their pride in building something that lasted beyond themselves, kind of like Saint Patrick’s quest in the place he labored and was once enslaved.

“I think the immigrants were very proud of their heritage, and they wanted to build a church that they could be proud of. And they saw other churches in the area where those ethnic groups were pouring their heart, soul and money into making something very beautiful,” O’Brien told ReligionUnplugged.com about Bayonne. “So I think the original parishioners that built this church… wanted the best.”

Paul Glader is executive editor of ReligionUnplugged.com and executive director of The Media Project. He has reported from dozens of countries for outlets ranging from The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Der Spiegel Online and others. He’s on Twitter @PaulGlader.