Contrasting Visions of Painter James Tissot, The Secular and Sometime Mystical Realist

“A discerning critic once rightly said of James Tissot, ‘He is a troubled soul.’ However this may be, there is something of the human soul in his work and that is why he is great, immense, infinite.” — Vincent van Gogh in a letter to his brother, Theo, September 24, 1880

(REVIEW) James Tissot (1836–1902) was a French artist whose work enjoyed enormous popularity and brought him great wealth. His works lost status soon after his death. In the following decades, when the art world turned against figurative art and the culture scorned religious faith, Tissot’s reputation faded because his art was both figurative and predominantly religious.

Tissot’s work is not easy to classify because it does not fit into any major art movement, and because he was an astute promoter of his work and earned a fortune twice over, even his business acumen makes him distasteful to some. Adding to all this, there are odd contradictions in his personality and way of life. These are best understood by looking at two paintings he did of two visions he experienced, one occult and one of Christ, both in the same year. But first, some necessary background.

A reevaluation

Quiet by James Tissot, with "La Mystérieuse” (“The Mysterious”) with a child and dog.

In recent decades, the art world has been reevaluating Tissot’s ouevre, and the judgment is much more favorable. For example, 129 of Tissot’s paintings of Old Testament scenes were recently shown (May 6-Dec. 30, 2022) at the Brigham Young University Museum of Art in an exhibit titled “Prophets, Priests, and Queens: James Tissot’s Men and Women of the Old Testament.” All Tissot’s Biblical paintings are held by museums, so they never come on the market. But whenever any of his secular works do come on the market, they sell for high prices.

For example, a year ago the Ulster Museum of Art mounted an exhibit (October 2021-January 2022) titled “Tissot’s Mysterious Irish Muse: New Acquisitions” to celebrate its new acquisition of one Tissot painting titled “Quiet” — for £90,000. “Quiet” is of Tissot’s model and mistress, who is painted as sitting with a young girl.

Tissot’s mysterious muse

Violet Newton, Kathleen Newton, Cyril Newton, and James Tissot

For decades after Tissot’s death, the lovely woman who modeled for “Quiet” and many of his other paintings was known only by the endearing titles he gave to the paintings, “La Mystérieuse,” “Mavoureen” (Irish for “my beloved”), and “La Belle [and La Ravissante] Irlandaise” (French for “the beautiful [and ravishing] young Irish woman.”

In 1946, a London journalist published a request for information about “La Mystérieuse,” and 71-year-old Lilian Hervey came forward and identified herself as the young girl in “Quiet” and other paintings by Tissot. She identified the mystery model as her aunt, Kathleen Newton. For evidence, she had original photographs of Newton with James Tissot.

Tissot’s background

Opening page from “The Life of Our Saviour Jesus Christ,” with illustrations and commentary, often called “Tissot’s Bible.

Tissot, who was born in the port of Nantes, France, was raised Catholic, but he fell away from the practice of his faith. Like many teenagers who think it’s cool to assume an identity different from the one into which they were born, Tissot anglicized his name to James when he was 18.

He was then generally known for the rest of his life as James Tissot, with several variants: His name on the title page of his wildly popular book of illustrations of “The Life of Our Saviour Jesus Christ,” which he completed after a mid-life reversion to the Catholic faith of his childhood, was J. James Tissot, and he was elsewhere sometimes referred to with the J. spelled out, as Jacques James Tissot, and then other times as James Jacques Joseph Tissot. In some recent writings, his name is given as James J. Tissot, and I’ve even seen J.J. Tissot, so the name by which he is known is even now quite fluid.

Tissot moved to Paris in 1856 or 1857 to study painting, and in 1861, when he was 24 or 25, he had six paintings accepted by the Salon. Not long after that, the government purchased one of his works for 5,000 francs. At first, Tissot painted scenes from antiquity, but then around 1863, he began to paint and sell large-scale, intensely detailed portraits and scenes of modern life.

In 1864 Tissot exhibited an oil painting and many engravings at the Royal Academy in London. By 1865, Tissot was earning 70,000 francs a year. Soon after he turned 30, he built an opulent villa on the most prestigious new thoroughfare in Paris, l’avenue de l’Impèratrice (The Avenue of the Empress).

“The Infallible,” a 1869 caricature by Tissot in Vanity Fair

In 1869, Tissot became friends with Vanity Fair of London’s founder, Tommy Bowles, and began contributing sharply observed caricatures under the pseudonym Coïdé to the magazine including one of the reigning Pope Piux IX. This one was labeled the Infallible, so that may indicate his satiric attitude to Catholicism at that stage in his life.

In 1871, at the age of 35, for unclear reasons perhaps having to do with his participation in the Franco-Prussian War and the following Communard uprising in Paris and/or out of ambition — which are among the many details of his life disputed among biographers — Tissot left (or fled) Paris, some say with only 100 francs in his pocket, and moved to London. He lived with Bowles for a year and continued to contribute caricatures to Vanity Fair.

Soon he became quite rich again from selling his paintings and etchings, mostly to newly rich industrialists and very occasionally to the nobility. This was even though some British reviewers accused his works of being vulgar and too French, although the “naughtiness” they disliked would not be considered naughty in our times. One of the criticisms leveled against Tissot was that he did not paint the “beau monde,” or high society, but the “demi monde,” the vulgar.

Tissot always deftly captured the details of fashion, décor, architecture and landscape, but at the same time he often portrayed his subjects in slightly risqué or embarrassing situations.

Tissot’s “London Visitors”

For example, in the painting “London Visitors,” two tourists, presumably a married couple, are painted standing outside the National Gallery in London. The husband is looking at a guide book. Much comment was made about the boldness of the direct gaze of the wife in the direction of the painting’s viewer. A smoldering cigar painted on one of the steps between the viewer and the woman hints that another man is the recipient of the woman’s gaze.

In 1872 Tissot moved into a fine home in St. John’s Wood and doubled the house’s size by adding a large studio and a conservatory. He landscaped the grounds to include grassy lawns, paved walkways, and stone patios with carved stone railings and planters, and he added a circular pond surrounded by full grown chestnut trees and black-painted cast iron columns, which were copied from the Parc Monceau in Paris.

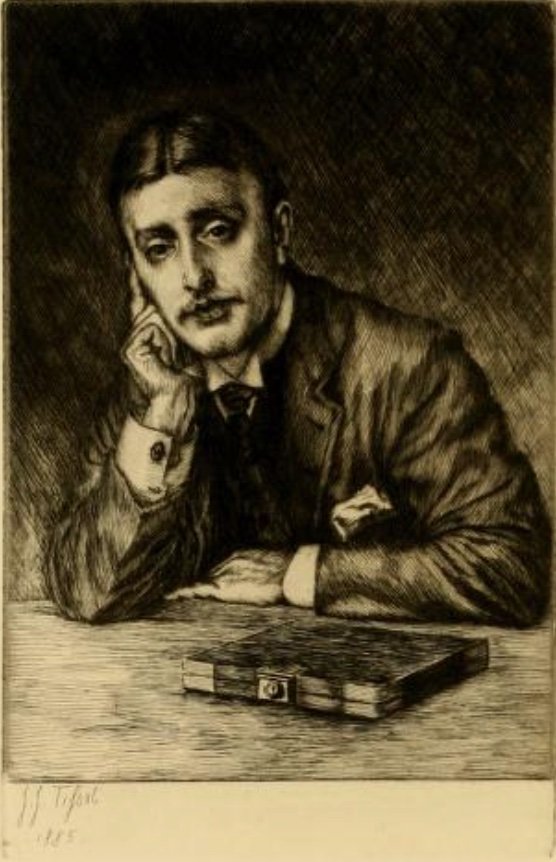

“Tissot” by Edgar Degas

When Tissot had studied in Paris, he made friends with Degas and other contemporary artists, and while he lived in London, these friendships continued. Tissot refused an invitation to exhibit with his contemporaries in the first exhibition of the works of the artists soon dubbed the Impressionists — Manet, Monet, Renoir, Pisarro and Morisot — in Paris in 1874. His reputation would undoubtedly have survived better into the 20th century if he had.

While Degas and Tissot were friends, before a split, Degas painted a portrait of Tissot.

How they met

In 1875, then-39-year-old Tissot met Kathleen Newton, who was a red-headed, 21-year-old Irishwoman with an illegitimate daughter. Kathleen had become a fallen woman in the eyes of respectable society when she was only 16 or 17.

In 1870, her father, who had retired from civil service in India, sent her back to Agra, India, from London by sea for an arranged marriage to an older widower, a surgeon named Isaac Newton. On the voyage she was pursued by a Captain Henry Palliser, a 31-year-old career naval officer. What happened between them and when remains obscure. Again these are among the many contradictory details surrounding Tissot’s life that are put forth by biographers.

Immediately after her arranged wedding, Kathleen confessed to a priest that she had sinned and still loved Palliser. The priest told her to tell the truth to her new husband. The Newtons never consummated their marriage, and he divorced her.

By the time Tissot met Kathleen, she and her daughter lived with her married sister, Mary Hervey, around the corner from Tissot, and her daughter, Violet Newton, was four years old. Both the child and her mother went by Kathleen’s divorced husband’s last name. In 1876, she gave birth to another illegitimate baby, Cecil, a boy. She gave the surname of her divorced husband to Cecil also.

Tissot’s paintings during this time were of Kathleen, but they also often included Kathleen’s two children and sometimes her sister and niece. The atypical family posed in sumptuous clothes from a stock of costumes purchased by Tissot, usually in Tissot’s luxurious furnished studio, against the backdrop of the conservatory filled with sunlight and giant plants, outside on the lawns, or at the edge of the colonnaded pond.

“Holyday” by Tissot

In the late 1870s, Kathleen contracted tuberculosis, and in November 1882, she died at the age of 28. Some say she died from the TB; many claim she committed suicide, either by jumping from a balcony or by overdosing on laudanum. One of the suicide stories says she wanted to spare Tissot, who was distraught watching her suffer. Another said she had read a letter in which Tissot said he was going to break off with her and committed suicide from despair.

Kathleen’s niece later wrote that Tissot draped the coffin with purple velvet and sat silently mourning and praying for four days in the dark with Kathleen’s body. I can’t find any mention of whether the unfortunate Kathleen received the last rites of the church, but I did find that she was baptized three days before her death. And it was firmly established by art historian Lucy Paquette that after a funeral Mass at a nearby Catholic Church of Our Lady in Lisbon Grove, Kathleen was buried at St. Mary’s Catholic cemetery. Kathleen’s burial in a Catholic cemetery casts doubt on the suicide stories, since suicides are not permitted to be buried in consecrated ground. Immediately after the funeral, Tissot packed up his paintings and left the house and everything else in it, and he also left both children behind with Kathleen’s sister and returned to Paris.

Cecil and his sister visited Tissot a few times after he left London. Cecil later in life told an interviewer that he and his family all knew Tissot was his father, and at one time as an adult Cecil refused a visit from Tissot because of Tissot’s neglect of him.

The fact that Tissot never acknowledged the boy seems cold. Some affection must have remained in Tissot’s heart because he kept “The Garden Bench” — a painting he did after Kathleen died of her looking adoringly at golden-haired Cecil with her daughter and niece beside her — hanging prominently in his home for the rest of his life. Perhaps, typical of many men who unwillingly father illegitimate children, he didn’t want to be burdened with caring for the child or even, in spite of his wealth, take on the financial burden of supporting Cecil if he legally acknowledged him. His closeness to Cecil in the earlier-shown family photograph suggests a real affection, and kindly motives may have been at work; perhaps he didn’t want to separate Cecil from his half-sister, aunt, uncle and cousins.

“Garden Bench” with Cecil Newton, his mother, Kathleen Newton, and his cousin, Lilian Hervey

Tissot’s contradictions

1901 Advertisement for The Live of Our Lord Jesus Christ

I never heard about James Tissot in art history classes I took while I was working toward a degree in studio arts because figurative art was scorned in the late 1970s. I only chanced across his name a few years ago, when I googled images to accompany a series of Facebook posts I was making about the gospel for each day in the traditional Catholic liturgical calendar. I often was glad to find Tissot illustrated many Bible stories, parables and personages that other well-known artists never got around to painting, especially since the images are free to download and reuse from the Brooklyn Museum.

As I later discovered, John Singer Sargent had urged the Brooklyn Academy of Arts and Sciences, soon to be renamed the Brooklyn Museum, to acquire Tissot’s illustrations and preliminary sketches for his astonishingly popular “The Life of Our Saviour Jesus Christ” (often called the Tissot Bible), which was lavishly printed using expensive chromolithography and engravings, with commentary by Tissot.

Sargent assured the founders that these works would make the Brooklyn Museum more famous than its competitor, the Metropolitan in Manhattan. Regrettably, after a few decades, the enthusiasm for these works of Christian realism faded, and the works were withdrawn from public viewing in the 1930s.

It’s illustrative of our present-day popular attitudes toward Christian values that while the mystical Tissot Bible illustrations languished in the archives, a painting that many consider blasphemous, titled “The Holy Virgin Mary,” was featured in the Brooklyn Museum’s 1999 exhibition of a traveling show of the work of Young British Artists, titled “Sensation.” The painting depicts an African woman partly draped in blue with a hint of a blue veil — with one distorted eye larger than the other and suggestively shaped red lips, one exposed breast made of elephant dung, and collaged “angels" made of cutouts of buttocks and other body parts from porn magazines floating around the cartoonish figure. The painting made its maker, Chris Ofili, famous and rich. It sold in 2015 for $4.5 million at Christie’s London, and it was donated in 2018 to the permanent collection of the New York Museum of Modern Art.

Tissot arrives in San Francisco

From Oct. 10, 2019, to Feb. 9, 2020, the San Francisco Legion of Honor museum mounted a show titled “James Tissot: Faith and Fashion,” in collaboration with Musée d’Orsay in Paris, which mounted the same collection of works under the title “James Tissot (1836-1902), Ambiguously modern” later that same year (June 23 to Sept. 13, 2020).

Sign for Tissot’s Faith and Fashion Exhibit at San Francisco’s Legion of Honor Museum 2/4/2020

Before I went, I started to read about him and learned about his reversion in his 40s to the Catholic faith of his childhood. The exhibit title used “faith” because the exhibit featured some of Tissot’s small-scale Biblical illustrations along with some larger-scale oils about the Prodigal Son and “fashion” because it featured a larger selection of his large-scale secular oil and pastel paintings.

In the Legion of Honor show, the last gallery before the exit was hung with his late works, including 22 out of a total of the almost 500 scenes from the New and Old Testaments that Tissot completed after he returned to practicing the Catholic faith.

To my surprise, I saw Biblical scenes were mixed in that gallery with other works reflecting a seemingly contradictory interest in spiritualism. Strangely enough, to my mind, Tissot painted both Catholic and occult subjects during the same time period.

Two paintings that embodied these two seemingly incompatible interests were of visions he’d had. The first is titled “The Apparition” or “The Mediumistic Apparition.” The second is titled “Jesus with the Desolate Poor,” and it has been known by multiple names, including “Inward Voices,” “The Ruins” and “Christ Consoling the Wanderers.”

The apparition: Tissot’s vision of his dead mistress

At least 10 years before Kathleen Newton died, while Tissot still lived in London, Tissot sought out practitioners of spiritualism, attended séances and started to collect books on the subject.

“The Apparition” OK

Sessions in which mediums, who ran the séances, supposedly contacted the dead were a rage that started in America and became popular in England throughout the last half of the 19th century, especially with those who, like Tissot, had lost loved ones. After religion-hating Victor Hugo lost his daughter Leopoldine in 1843, Hugo engaged in séances, as did Mark Twain’s wife after the loss of the Twain’s favorite daughter, Suzy, in 1896, and skeptical Twain even attended a few séances himself (although he later wrote a satire on one).

Tissot’s grief at Newton’s death motivated him to seek to reach her again through séances. After he returned to Paris to live, Tissot became friends with a medium named William Eglinton. Eglinton, like many practitioners of spiritualism, claimed séances prove scientifically the existence of an afterlife. This claim of scientific investigation appealed to people who were dissatisfied by the prevalent materialist explanation for reality, which denied the existence of God and of the human soul and were left with the doleful prospect of annihilation at death.

On May 20, 1885, two days before Victor Hugo died — thereby resolving all questions he may himself have had about life after death — Tissot participated in a séance held by Eglinton on a visit back to London. Even though Eglington was proven to have used fraudulent methods in his séances, Tissot and other witnesses saw two figures materialize with Eglington channeling them. The apparition is described in this excerpt from “Twixt Two Worlds: A Narrative of the Life and Work of William Eglinton,” published by The Psychological Press in 1886.

Mr. Eglinton took his place in an easy-chair close to M. Tissot's right hand, and so remained the whole time. ... After conversing for a time two figures were seen standing side by side on M. Tissot's left hand. They were at first seen very indistinctly, but gradually they became more and more plainly visible, until those nearest could distinguish every feature. The light carried by the male figure (“Ernest”) was exceptionally bright, and was so used as to light up in a most effective manner the features of his companion. M. Tissot, looking into her face, immediately recognised the latter, and, much overcome, asked her to kiss him. This she did several times, the lips being observed to move. ... After staying with him for some minutes, she again kissed him, shook hands, and vanished.

Soon after the séance, Tissot painted “The Apparition,” which showed the spirit guide and Kathleen as he had seen them in the séance. Tissot exhibited the painting but never sold it. He kept it hanging in his home until his death.

“Twixt Two Worlds” continues:

Tissot’s “Jesus Among the Desolate Poor"

This incident M. Tissot subsequently chose as the subject for a mezzotint entitled “Apparition Mediunimique,” which has now become the wonder and talk of the artistic world. ... This is not the only acknowledgment which M. Tissot has rendered of his indebtedness to Mr. Eglinton's mediumship. When made aware of the proposed publication of this volume, he very kindly offered to present Mr. Eglinton with a portrait etching to serve as a frontispiece, his idea being to impress his pencil and graver into the service of Spiritualism.

The last Legion of Honor gallery before the exit also displayed a copy of “Twixt Two Worlds” with the engraving of Eglinton in the frontispiece, done by Tissot.

Tissot’s experiments in spiritualism put him in grave spiritual danger, as Father Robert Hugh Benson dramatized in his novel “Necromancers,” which was published in 1907, after Tissot’s death. Benson was an Anglican convert and the author of a dystopian novel titled “Lord of the World” that is still read today, about the Antichrist’s rise to power in a world where religion has almost been completely exterminated.

In “Necromancers,” Father Benson explained through the mouth of a priest character that when phenomena at séances were not fraudulent (although they often were), and when the witnesses irrefutably saw and sometimes even touched an apparition of a dead person, the apparition was generated by demonic manipulation of the medium, with the purpose of opening viewers to possession.

In a 1906 essay that developed the ideas fictionalized in the book, Father Benson wrote that spiritualism, which had in times past been called necromancy, was not science but a spreading form of religion that Christians must avoid:

Except in the cases where materialists have been convinced through means of Spiritualism of the existence of another world, it is impossible to point to any spiritual or mental gain to balance the extremely numerous losses on the other side. ... The losses are loss of the souls who are captivated, deceived, and possessed by the spirits who masquerade as spirits of the beloved dead. ... So far as the alleged phenomena are genuine, the Catholic Church accounts for them by the action of evil discarnate spirits — called “fallen angels.” She utterly rejects, therefore, their testimony, and warns her children against accepting it.

Tissot seems to have been one of the fortunate ones whose experiences in spiritualism led to belief in the reality of life after death, which may have led him to another vision he had, this time of Christ. If you believe in spirits, the Christian revelations of heaven and hell are no longer so difficult to believe.

‘Jesus Among the Desolate Poor’: Tissot’s vision of Christ

In 1885, the same year as that first vision of his dead mistress, Tissot had his second vision in the Church of Saint-Sulpice in Paris. So it followed that in the same year he painted his first vision, Tissot also painted the second, which is variously known as “The Ruins,” “Inner Voices,” “Christ Consoling the Wanderers” and “Jesus Among the Desolate Poor.”

Tissot’s own words follow:

Tissot’s “Jesus Among the Desolate Poor"

It came about in a mysterious way — one that I do not pretend to understand. I was then painting a series of fifteen pictures, to be called “La Femme à Paris,” representing the pursuits of the society woman of the gay capital. At that time, it was fashionable to sing in the choir of some great church, and I wished to make a study for my picture, “The Choir-singer.” For this purpose I went to the Church of St. Sulpice during mass, more to catch the atmosphere for my picture than to worship.

But I found myself joining in the devotions, and as the host was elevated and I bowed my head and closed my eyes, I saw a strange and thrilling picture. It seemed to me that I was looking at the ruins of a modern castle. The windows were broken, the cornices and drains lay shattered on the ground; cannon-balls and broken bowls added to the debris.

And then a peasant and his wife picked their way over the littered ground; wearily he put down the bundle that contained their all, and the woman seated herself on a fallen pillar, burying her face in her hands. Her husband, too, sat down, but in pity for her sorrow, strove to sit upright, to play the man even in misfortune.

And then there came a strange figure gliding towards those human ruins over the broken remnants of the castle. Its feet and hands were pierced and bleeding, its head was wreathed with thorns, while from its shoulders fell an Oriental cloak inscribed with the scenes, the Fall of Man, the Kiss of Judas.

And this figure needed no name, seated itself by the man, and leaned its head on his shoulder, seeming to say more by the outstretched hands than in words: “See I have been more miserable than you; I am the solution of all your problems; without me civilization is a ruin.”

The vision pursued me even after I had left the church. It stood between me and the canvas. I tried to brush it away, but it returned insistently. Finally I was attacked by fever, and when I was well again I painted my vision.

After the second vision, Tissot returned to the Catholic faith of his childhood. During the rest of his life, Tissot traveled to the Holy Land multiple times, researching details for his series of dramatic watercolor illustrations of events and people from the life of Christ and the Old Testament.

But even though he returned devotedly to his childhood faith, he seemingly never repudiated spiritualism. A collection of hundreds of books on spiritualism — out of 4,500 total about other topics — was found in his library after his death. Tissot often showed those who visited his chateau a room that he set aside for spiritualist rituals, items used in the séances, and they saw his oil painting “The Apparition” hanging in that room. This odd habit of showing these things to his visitors, however, might have been part of his sense of humor, since he would assume a spectral voice when talking about the objects and their ritual uses.

1885 until the end of Tissot’s life

Some who write about Tissot’s life after his return to Catholicism incorrectly claim he became a monk, perhaps confused because the Chateau de Buillon he inherited from his parents was originally and was still occasionally referred to as the Abbaye de Buillon, although the abbey was destroyed during the French Revolution. The chateau was a luxurious property, and Tissot expanded it at great expense. Instead of isolating himself completely, as the story mistakenly went, Tissot continued to mingle with Parisian society — at least to the extent necessary to promote sales of his work — and kept up his Parisian home.

Chateau de Buillon, Tissot estate.

On his research trips to the Holy Land, he lived simply and traveled far to record scenes and the ways of the inhabitants from actual observation, acting on his assumption — often disputed by critics — that these things had not changed significantly since Jesus’ time. He began each day with morning prayer with a local order of nuns, rode out on expeditions on a donkey, with his art supplies in saddle bags, usually with a local guide. He would sketch and photograph backgrounds, such as a carpenter shop-like one in which Joseph might have worked, a view from the Mount of Olives or a fig tree. And he’d make studies of types of people, such as women drawing water at a well or shepherds in the fields, noting how people wore their hair, their clothing — any detail that might catch his eye.

Tissot later described to a reporter how he gathered details, prepared his paintings and entered into a mystical state when creating his biblical compositions in the following quotations published in McClure’s magazine, March 1899:

In the evenings after his excursions on muleback, Tissot jotted down in an album of little pictorial notes, each one about the size of a postage stamp, just the roughest pencil scrawling, to bring back a hint of composition. ... M. Tissot would enlarge one of these into a more detailed sketch, outlining the background and central figures in heavy black line; the whole, still formless, the merest skeleton of a picture, with only black ovals for the heads and a few rough lines for the bodies.

But now a strange thing would happen, a rather uncanny thing. ... M. Tissot now in a certain state of mind, and having some conception of what he wished to paint, would bend over the white paper with its smudged surface, and, looking intently at the oval marked for the head of Jesus or some holy person, would see the whole picture there before him, the colors, the garments, the faces, everything that he needed and had already half conceived. Then, closing his eyes he would envision the scene he wanted to portray.

When he was back in Paris after his travels, Tissot would sometimes receive vivid impressions of a scene to paint even walking down the street:

One day, for instance, while strolling in Paris, near the Bois de Boulogne, M. Tissot suddenly saw before him a massive stone arch out of which a great crowd was surging. ... And the multitude, with violent gesture, lifted their hands and pointed to a balcony high up on a yellow stone wall where stood Roman soldiers dragging forward a prisoner clad in the red robe of shame. Hanging down from the balcony was a piece of tapestry . . ., and over this the prisoner was bent by rough hands and made to show his face to the crowd below, and it was the face of Jesus.

Tissot reproduced what he saw in this vision in his painting, “Ecce Homo,” “Behold the Man.”

Tissot’s “Ecce Homo”

Tissot worked on the Bible illustrations in both the chateau and in the lavish mansion he still owned in Paris, while attending Mass every day.

A few examples of his continued showing and selling of his non-Biblical works indicate how far he was from being in exile from society. In 1887, after the publication of “The Life of Christ,” he exhibited one painting at Nottingham Castle and another at Newcastle, and in 1888, he exhibited three works in Glasgow. In 1889 won a gold medal for a series of larger-scale oil paintings of the Prodigal Son, the same year he traveled the second time to the Middle East to continue research for his illustrations of Christ’s life. In 1893, he exhibited his Prodigal Son Series and one of his pastel portraits at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

When he exhibited 270 of the final total of 365 drawings for “La Vie de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ” (“The Life of Christ”) stole the show at the Salon of 1894. One account reads:

The pictures were given a gallery and a special catalogue. The public reaction was astonishing: one headline read, “THE CHAMP DE MARS SALON; JAMES TISSOT’S LIFE OF CHRIST A MARVELOUS SERIES. Women Weep as They Pass from Picture to Picture.”

Around that time, he also worked on a colossal Christ Pantocrator for the dome over the altar of the church at the Dominican convent of the Annunciation in Paris, which was installed in 1897.

After the Biblical illustrations were presented to wild acclaim in Paris in 1894, they later traveled to London and the United States, visiting Manhattan, Brooklyn, Boston, Philadelphia and Chicago, where they attracted similar acclaim. For one example, 23,000 attended the Chicago exhibition.

So, it cannot be denied that Tissot also actively marketed his work and cultivated connections of his work. He aggressively promoted ticketed exhibitions of his Biblical illustrations and the sale of the illustrations to the Brooklyn Museum.

Several writers about Tissot have noted that in his obituary in The Evening Post, at his death in 1902 — without identifying which Evening Post — Tissot was compared to William Blake, but “uniting as Blake never did, and as no other prominent artist has done, the mystical and ideal with an intense realism.”

"Jesus Transported by a Spirit onto a High Mountain”

While his illustrations were as realistic as his earlier work, some saw them as not being realistic because they treated miraculous events. Many of the scenes verged on being surrealistic. One of the most well-known is a portrayal of one of Satan’s temptations of Christ. The white robed serene figure of Jesus with his arms outstretched is lifted against a gray sky above a low dark mountain range by a long black faceless ominous shadow.

Because of scenes like that, Tissot is often written about as cinematic. His works, even after they were mostly forgotten, influenced most portrayals of the events of the Bible and of the Holy Land and made a big impression on filmmakers.

“Wildly popular during Tissot’s lifetime, these religious images ... have since influenced filmmakers from D. W. Griffith (“Intolerance,” 1916) to William Wyler (“Ben-Hur,” 1959) as well as Spielberg and Lucas.” —From the Legion of Honor description of the “Faith and Fashion” exhibit

Tissot’s style

Tissot’s earlier paintings in oils and pastel chalk are large-scale and technically brilliant and are so detailed they are sometimes called hyperrealistic or superrealistic. In contrast to his earlier works on canvas and linen, Tissot’s biblical works are painted on gray laid paper, using gouache (opaque watercolors) instead of oils or pastels. These paintings are small, usually no bigger than a sheet of legal paper.

Gouache is usually applied very loosely by other artists. But Tissot’s little gouache paintings are painstakingly rendered. If you look closely at the illustrations even in reproduction, you can see that they are done with thousands of skillful strokes of color, similar to his secular works, but in a much more subdued and restricted color palette.

The Magi Journeying

He doesn’t use typical illustration techniques, either, in which shapes painted in watercolor are outlined with black ink. In fine-art style, Tissot usually differentiates his figures from their backgrounds, not by outlines but by color changes, just as the edges of things seen in nature are not outlined. Sometimes his use of gouache for such precise detail has been criticized as stilted and inappropriate for the medium, but the deft draftsmanship he honed in his hundreds of other works is undeniable in the Bible illustrations, and the way he independently adapted gouache to his own painterly technically masterful style has resulted in depictions that have moved countless viewers — even if he didn’t follow expected technique for watercolor.

Some see the illustration’s colors as drab, and they could be seen so, especially in contrast with his more colorful paintings of secular life, in the same way the Holy Land seems drab to many. Tissot, however, was struck with its colors. "There are no colors in the world like those of Palestine; the very earth has shades unknown elsewhere; the waters are deeper in color from that glorious sky; it is a world of beauty all its own.”

A complex human soul

“Although Tissot himself promoted Buillon as a place where he sought solitude so he could work on his religious illustrations, in reality he remained an artist who straddled two worlds, having never completely abandoned his fashionable life in Paris.” — Melissa Buron in “’Twixt Two Worlds: The Visions of James Tissot” (2022)

What can be made of all these facts about this complex artist?

Tissot united a businessman’s skills of self-promotion and money making with a love for beauty, fashion and luxury, and then added into the mélange after his conversion a newfound intense prayer life, forming a new goal to bring his visions of the events of the Bible to the world as realistically observed and as mystically imagined as possible — while at the same time staying enthusiastic for the occult, apparently not seeing any contradiction in all of these disparate things.

In short, Tissot is an artist whom we have to acknowledge, as Van Gogh did, as a greatly, immensely talented Catholic Christian believer — while not denying the dark sides to his nature we glimpse behind the narrative he presented to the public about his life.

Roseanne T. Sullivan writes about sacred music, liturgy, art, literature and whatever strikes her Catholic imagination. She has published many essays, interviews, reviews and memoir pieces in print and online publications, such as Dappled Things Quarterly of Ideas, Art and Faith; Sacred Music Journal; Latin Mass Magazine; National Catholic Register; New Liturgical Movement; and Homiletic and Pastoral Review.