Faint Signs Of Faith Part 2: Churches In Prague Serve As Art And Tourism Sites If Not Houses Of Worship

PRAGUE— Tereza Gavenda walks the halls of the Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia in Prague, admiring each piece of artwork within its dark stone walls. Sculptures, paintings and altarpieces fill each room — pieces of National Gallery Prague’s permanent exhibition “Medieval Art in Bohemia and Central Europe 1200-1550.”

This convent dates back to 1231. It was built on land donated by King Wenceslaus 1 of Bohemia along the banks of the mighty Vltava River. Now, as the Czech Republic has become one of the most atheistic countries on earth, St. Agnes serves as an art exhibit space as part of the National Gallery Prague chain of locations in Prague.

Tourists visiting the Church of Our Lady Triumphant, where the famous sculpture of the Child Jesus is housed.

Photo credit: Anderson Ayala Giusti

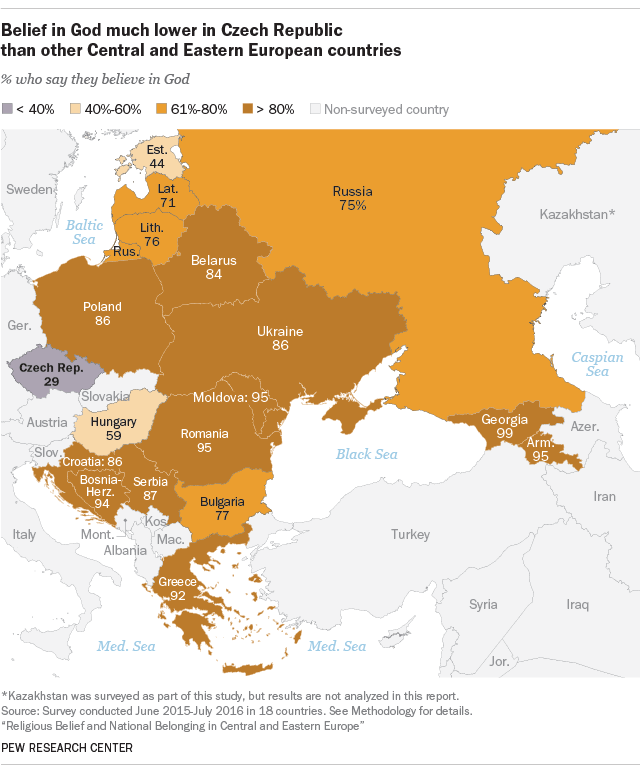

Almost all of the pieces are religious, taken from churches, basilicas and private chapels. They are echoes of a glorious religious past — one that contrasts with the fact that most of the Czech Republic’s population today is religiously unaffiliated. In fact, according to Pew Research Center’s 2016 survey, 64 percent of Czech adults say they were raised without a religious affiliation.

Gavenda, 23, a recent graduate from Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic, is visiting Prague while she tours the country before starting her new job later this month. Although she just graduated with a degree in economics and public policy, Gavenda has always had an appreciation for art — especially ancient art.

Gavenda grew up in a Catholic family, although they were not actually very religious. The one part of religion that she liked when she was younger was the art found in churches. In fact, Gavenda passed the time during Christmas Eve Mass and Easter Vigil looking at the icons, altarpieces and stained glass.

“The one part of Mass I could pay attention to was the church,” she said. “It was so beautiful.”

A gilded artwork at the Church of Our Lady Triumphant in Prague.

Photo Credit: Anderson Ayala Giusti

That’s why NGP’s collection at the convent is perfect for someone like Gavenda.

The convent is a national heritage monument and has deep history within the city. St. Agnes of Bohemia, who was canonized in 1989, was originally a princess and sister to King Wenceslaus I. She founded the convent and monastery of the Orders of Poor Clares and Friars Minor with the money and support of her family in the 1230s.

According to the convent’s self-guided tour, St. Agnes took her monastic vows in 1234 and

became the convent’s abbess shortly after in 1234.

After hundreds of years of fires, plundering and renovations, the convent became the property of

NGP in 1963. The medieval art exhibit was officially opened to the public in 2000, where it remains to this day.

Shimmery stained glass windows, double-sided paintings used in liturgical processions and even a gilded monstrance are on display. Descriptions are included next to each piece, although they sometimes leave room for interpretation.

This statue is thought to be a wood-carving of St. Procopius. Like many art pieces found within National Gallery Prague’s exhibition in the Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia, information on the statue is not comprehensive. Photo Credit: Soraya Keiser

Next to a wood-carved statue with the head missing, an inscription reads “Torso of St. Procopius (?),” and below, “origins allegedly in Strakonice.”

Underneath the title of “Case for the Painting of Madonna of Vyšehrad,” it reads: “Prague, probably 1397.”

Next to another statue of the Madonna, it simply says, “Madonna, Central Europe, around 1420.”

These are just a few examples of the ambiguity found all throughout the gallery. Whether through age, plundering or lack of records, many details about the art pieces have been lost.

However, this doesn’t take away from the viewing experience for Gavenda. In fact, it makes her even more curious about the time period.

“There’s a mystery surrounding them,” Gavenda said.

An outer wall houses the Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia and its gardens. Established in the 1230s, the convent is now owned by National Gallery Prague and houses a permanent exhibition titled Medieval Art in Bohemia and Central Europe 1200–1550. Visitors can also follow a self-guided tour through the convent and explore sculptures in the gardens. Photo Credit: Soraya Keiser

Although information may be lost, NGP is dedicated to maintaining these beautiful pieces of history and the convent and gardens that surround them. No matter the fact that the majority of the country is atheist.

“It is our history,” Gavenda said.

This statue is thought to be a wood-carving of St. Procopius. Like many art pieces found within the National Gallery Prague’s exhibition in the Convent of St. Agnes of Bohemia, information on the statue is not comprehensive. - Reporting by Soraya Keiser.

Vignette 2:

The Home Of Empty Churches

With a population of 1.3 million people, Prague, a city famous for its majestic churches and beer, is seeing a major decline in its religious population. According to the 2017 report by the Pew Research Center, 72 percent of people in the city do not associate with a religion, 46 percent believe in “nothing in particular,” and 25 percent say they are atheist.

“Even in the former Eastern Bloc that was dominated by the officially atheist Soviet Union throughout much of the 20th century, the Czech Republic is a major outlier by both of these measures,” Jonathan Evans said in an article for the Pew Research Center.

Taking a look at the history of Prague, the city had a prominent Catholic community until it hit a fall in 1415, when Jan Hus was burned at the stake for heresy by the Catholic Church.

“Responding with horror to Hus’ execution, the people of Bohemia moved even more rapidly away from papal teachings, prompting an announced crusade against them,” an article from the People’s World said.

The pope ordered all supporters and reformers following in Hus’ steps to be killed. In response, the Hussites, followers of Hus, became militarily powerful and fought crusades against the Catholic Church until 1434. Finally, in 1436, a compromise was formed, and the fighting ended.

About two centuries later, the Holy Roman Emperor Ferndinand II imposed Catholicism as the mandatory religion. Outraged, the Bohemian nobility threw Ferdinand’s representatives out the window of Prague Castle. This act became known as the defenestration of Prague and started the infamous Thirty Years’ War, where Protestant and Catholic states fought against one another. The war ended with the Peace of Westphalia, which put an end to Roman Catholic supremacy.

In 1918 Czechoslovakia became a republic state but was soon invaded by Hitler in World War II. With Stalinization during the Cold War, communism took over in the Czech Republic, influencing almost all facets of life for its citizens. Anything that could be a possible threat to the Communist Party was obliterated — including religion.

“The Communists took over Church property, closing down all 216 monasteries in the country during 1950 and most of the 339 convents,” Tracy Burns said in her article “Life During the Communist Era in Czechoslovakia.”

“Some clergymen were murdered, while others found themselves sharing prison cells with murderers or the insane, or they were sent to labor camps or placed in the army.”

Communists feared that religious organizations, specifically the Roman Catholic Church, might be a threat to their existence. This suppression of religion lasted for 40 years until the fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov. 17, 1989.

While the end of communism presented the Czechs and those in Prague with freedom of religion, the people have swayed away from churches to this day. While many blame the years of Communist takeover for this outcome, an article by PragueLife says it was actually an accumulation of Czech history.

“Communism did not bring its rejection of religion until centuries of disfavor for Catholicism in Czech culture,” author Michaela Dehning says. “From then, it was not difficult for atheism to become solidified in the nation’s beliefs.” - Reporting by Mariya Rajan and Kennedy Kruse.

Vignette 3: A Church Showed The Power Of Resistance In WWII

The destiny of the Orthodox Church of Sts. Cyril and Methodius in Prague changed forever on June 18, 1942. On that day Nazi troops attacked the building where members of the Czechoslovak resistance were hiding after having assassinated Reinhard Heydrich, governor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia named by Adolf Hitler. The Germans had begun occupying parts of Czechoslovakia in 1938, creating the protectorate the following year.

Paratroopers Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš, who were responsible for Heydrich’s assassination, and five other members of the resistance clashed with 750 Nazi SS soldiers. Kubiš and two others died after the battle. Gabčík and the remaining men killed themselves in the crypt. After the paratroopers’ deaths, the Nazis persecuted Bishop Gorazd and other priests who had given shelter to the members of the Czechoslovak resistance. They were all executed in the following days.

In the crypt of the church where the attack took place, tourists can visit an exhibition that recounts the details of the Anthropoid operation, the name given to Heydrich's assassination plan. The memorial has photographs, objects and documents. Admission is free. On a warm Sunday in July, the place fills up quickly as the staff welcomes visitors and explains to them the details of the events that happened 80 years ago. “It’s something we’re very proud of,” said Raila Hlavsova, a historian who works in the church’s basement, which is managed by the Historical Army Institute.

“It’s a never ending story. Even today I learned something,” she added, explaining that descendants of those who were killed for being associated with the Anthropoid operation come to visit often telling staff new details of their relatives. “We’re the most important memorial of the Second World War in Prague,” she said.

After the bishop and priests were executed, an oral history began to keep their memories alive. Three years after WWII ended, communism arrived in Czechoslovakia in 1948. At the time “few people knew what had happened here,” said Hlavsova. The Orthodox priests kept the story alive, and in 1987, Bishop Gorazd was proclaimed a saint by the Orthodox Church. Others close to the church who were involved in giving shelter to the paratroopers were proclaimed martyrs. “They became heroes for all people, not only Orthodox,” she said.

The events that took place after Heydrich's assassination even crossed the borders of Czechoslovakia. In the search for the paratroopers, the Nazis annihilated the town of Lidice on June 9-10, 1942. They killed men, took children and sent women to concentration camps. News of the massacre traveled fast, and within one year Lidice’s name appeared on streets and squares in cities all over the world, including some as far as in Latin America, said Hlavsova. It even became a girl’s name as a reminder that Lidice exists. As for the Church of Sts. Cyril and Methodius, it became the main cathedral for Czech and Slovak Orthodox. “It gave strength to people from the Orthodox Church,” she said. - Reporting and photos by Graciela Ibanez.

Vignette 4: Church Of Our Lady Triumphant

The churches of Prague never seem to be alone. The paradox is that those who fill it are not precisely the parishioners, but the tourists. They are easily recognized not only for taking pictures of each painting or looking in detail at the architecture, but also for speaking a language other than Czech. This is the case of the well-known Church of Our Lady Triumphant, where the famous sculpture of the Child Jesus is housed.

It is a church originally built as a small temple in the 16th century (1611-1613), when Europe saw clashes between Christians (Catholics and Protestants). Today it stands tall in the heart of Prague, boasting five centuries of not only history, but also spiritual treasures.

The people who enter crowd mainly around the figure of the Child, who is surrounded not only by visitors but also by hundreds of plaques hanging on the nearby walls. Hundreds of names are read on them, all with a “thank you” message in any language. People from all over the world have come here to ask for and venerate the miracles that the Child of Prague has granted.

The statue of the Child arrived in the 17th century and has remained a permanent feature of the church ever since. Toward the end of the temple, far away and hidden, is a small museum where very few people seem to want to enter. Only a few do so to learn a little more about the history of the famous sculpture. It is a reflection, perhaps, of what happens in the tourist's mind: remaining only in the most immediate and superficial.

In the opposite corridor is the sacristy, in the most intimate, where some priests and the Discalced Carmelites are. They are another element of religious life: the ones in charge of taking care of the temple, so they are always walking from one place to another. Perhaps they are the most Czech thing the temple has at the time, because other than a couple of older parishioners, there don't seem to be any local people in the temple. Even the priests are almost all foreigners.

The people of Prague, as is happening throughout Europe, have been distancing themselves from the prominent religion in their city. The churches are packed, but with tourists who enter only for fleeting moments. It is a very evident symptom that Catholicism is not adding parishioners as in recent times, when the church of Prague (and Czechoslovakia) was the only institution of resistance against Soviet communism, as recognized by Father Anastasio, who has worked in this church for almost 30 years.

“If they (the communists) destroyed the churches, then they destroyed Prague. The city from its origins has always been of religious tradition,” he pointed out. Of course, the priest cannot avoid recognizing that the number of Christians has dropped in recent years, without this implying a total loss of spirituality in society. Many of the moral principles and values that all share are, in fact, of Christian roots based on tolerance, solidarity and temperance.

Even so, the church itself has also had to adapt to its new times, and for this reason the souvenir shop is located right at the entrance, which is also the obligatory point of departure for all visitors. There are memories and objects full of meaning, although never with the same weight as the one felt inside the temple.

Religious life in Prague has become another tourist spot, without this implying anything negative either. This can add not only income from sales but also some parishioners in other latitudes.

However, the phenomenon seems to be in the city dwellers of Prague, who look scattered in the face of the spiritual and religious wealth that rests in their city. But the Catholic Church persists, and may once again be a bastion of resistance if the situation calls for it.

Soraya Keiser is a student at Bethel University in Minnesota, where she is majoring in journalism and international relations. She was the managing editor of her student newspaper and interned with The St. Paul Pioneer Press.

Mariya Rajan is a founding member of Newsreel Asia in India.

Kennedy Kruse is a student at Patrick Henry College in Virginia, where she worked on the school newspaper.

Graciela Ibanez is a professor at Universidad Gabriela Mistral’s journalism school in Santiago, Chile. Ibanez has a master’s from Columbia Journalism School in NYC and has written for several publications.

Anderson Ayala Giusti is an economics writer and UX specialist based in Caracas, Venezuela.

Editor’s Note: This is the second installment in a 7-part series reported by 24 young journalists from 16 countries who studied at the European Journalism Institute in Prague in July of 2022. EJI is co-funded and programmed by The Media Project (the parent non-profit of ReligionUnplugged.com) and The Fund for American Studies. EJI 2022 took place at Anglo-American University.

-

Almost all of the pieces are religious, taken from churches, basilicas and private chapels. They are echoes of a glorious religious past — one that contrasts with the fact that most of the Czech Republic’s population today is religiously unaffiliated.

-

DesAs I researched media content, it became quite clear to me that churches find their place in the news primarily (if not only) when the subject is business or economics related — church properties and estates — as if shaking away the communist past; political and/or financial correlations. Looking at the local religious life — it barely ever is a subject of media focus.

-

Old Prague’s Jewish quarter was once a walled-off ghetto where the bulk of Bohemia’s Jewish community resided apart from the Christian majority, partly for their own protection. It is now little more than an open-air museum

Read More → -

Muslim tourists and locals in Prague find solace in their accessibility to Middle Eastern, halal food along with tourist hot spots. What’s special about such accessibility is that digital media now promotes “halal tripping” or “halal tourism.”

Read More → -

Although the Czech Republic is the most atheist country in the world, people still practice religious traditions today. Simultaneously, there are many factors contributing to the change of religious food culture in the Czech Republic, like globalization, tourism and immigration.

-

Regardless of one's religious affiliation, Prague’s Church of Our Lady Victorious’ breathtaking architecture and rich history make the church an irresistible attraction for travelers. While most can find this to be a unique spiritual experience, locals of Prague have a rather interesting relationship with the church.