Samaritans Number Less Than 1,000. Here's How Their Tradition Survives In Israel

Mount Gerizim. Photo by Gil Zohar.

(ANALYSIS) QIRYAT LUZA, West Bank— For Israeli Jews, the month of Cheshvan is sometimes called “Mar Cheshvan” — meaning the bitter Cheshvan — since it is the only month in the Hebrew lunar calendar that does not include a holy day, or at least a holiday.

But those feeling the need to celebrate God’s graciousness can visit the village of Qiryat Luza atop Mount Gerizim — to the south of the Palestinian city of Nablus — to join in the seven-day biblical harvest festival of Sukkot, which Samaritans are observing Oct. 20-26 — one month after Jews.

The ranks of the once mighty Samaritan people reached 3 million in biblical times but were reduced by persecution and apostasy to 146 by 1918. Today they number 814, half of whom live here on this picturesque mountaintop in the West Bank. The other half live in Holon, a city on the coastal plain adjoining Tel Aviv to the south 75 kilometers (46.5 miles) to the west.

In this week, they observe the Sukkot holiday, a harvest festival that celebrates the protection God provided to the children of Israel when they left behind slavery in Egypt and wandered in the desert.

Speaking in a mixture of Arabic, Hebrew and English, community spokesman Hosni Wasef explained that some 90 “sukkot” — a term that also refers to temporary tabernacle huts made for the holiday — had been erected in Kiryat Luza and slightly fewer in Holon.

Sitting barefoot, he recently welcomed a group of journalists in the parlor of his spacious, elegant apartment that doubles as his office. The modern stone-clad, three-floor, concrete building erected in 1994 adjoins the traditional site of the Paschal lamb sacrifice ceremony held in April. The trenches were filled with garbage thrown there by children, his daughter Selwa noted with some embarrassment.

READ: Priest Hopes To Rebuild Crusader-Era Church Of John The Baptist In Palestine

Wasef, the director of the Samaritan Museum here and the younger brother of High Priest Abdallah Wasef, proudly noted he has written 20 books about his people and their faith. He calls himself a leading figure globally in the study of the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt — which, like for Jews, marks the beginning of their peoplehood. His brother, 85, has served as high priest for the last seven years, and will continue do so until his death, when he will be replaced by the eldest member of his priestly family.

The Samaritans celebrate Sukkot every year, beginning on the full moon of Tishrei 15, just as the world’s Jews do. But since the sect — which traces its origins to the Northern Kingdom of Israel and the tribes of Ephraim, Menasseh and Levi — doesn't accept the rabbinic calendar reforms from the Talmudic period in the sixth century, their Bible-based holy days sometimes fall one month later. While Judaism fixes the order of the seven leap years in a 19-year cycle, the high priest decides when the extra months will occur. Hence the disparity in the calendars.

Samaritan High Priest Abdallah Wasef. Photo by Gil Zohar.

Unlike Jews, who build their sukkot outside, the Samaritans construct their elaborate sukkot indoors, suspended from a frame attached to the living room ceiling. They have been doing so for the last 1,500 years. In the Byzantine period, the Samaritans were persecuted, and their outdoor sukkot were often vandalized by their Christian neighbors.

Like Jews, they utilize “skhahk” — greenery such as palm fronds — to cover their sukkot, but only the top layer. Beneath the palm leaves, the Samaritan sukkot is decorated with fruit and vegetables arranged in decorative geometric patterns and hung like a chandelier from a permanent ceiling mount.

The colorful display in remembrance of the Garden of Eden can often involve 100 kilograms (220 pounds) of seasonal fruit, such as pomegranates, apples, guavas, oranges, peppers and, of course, “etrogim” — citrons, the biblical citrus fruit that is akin to a lemon. The display is rounded out with colored lights and foil decorations that might be used for Christmas or Ramadan.

Symbolizing the Samaritans’ confusing status in the middle of Israelis and Palestinians, Selwa pointed out that water is provided by Israel while electricity comes from the Palestinian Authority grid. At that moment, a PA garbage truck rolled by with a sign noting it was from Turkey. Some Samaritans hold Israeli, Palestinian and Jordanian passports, her father said.

Interviewed in his home — one floor below his brother’s apartment — Abdallah Wasef wore a traditional robe made from golden silk imported from Damascus and a red turban on his head, wrapped with a white cloth.

“We are seekers of peace,” he explained in Arabic. “We are living between the Jews and the Palestinians. Both are supporting us. Peace is better than war.”

And what of the future?

Without hesitation, the elderly high priest replied that the ruins of the temple in the national park atop Mount Gerizim, marking the spot Samaritans believe Abraham was ready to offer up his son Isaac as a sacrifice, “will be rebuilt when God wants, when the time comes.”

The religion and history of the Samaritans

After the death of King Solomon in about 920 B.C., his northern subjects gathered at Shechem — modern-day Nablus — to secede, rejecting his arrogant heir Rehoboam (1 Kings 12:1-20). The breakaway kingdom bolstered its political independence from Judah by theologically challenging the beliefs of the old kingdom.

The Samaritans maintained that God’s chosen site for his sanctuary was Mount Gerizim, an 881-meter (2,890-foot) peak looming over Shechem from the south, rather than Mount Moriah in Jerusalem 63 kilometers (39 miles) to the south.

The Samaritan religion became fossilized in the centuries following the split between Israel and Judah. Very little innovation in thought, literature or social organization has arisen over the millennia, affording a telescopic glimpse of the pristine Judaism of pre-Rabbinic times. Even the Hebrew font they use is ancient, preceding alphabet reforms made by Jews some two-and-a-half millennia ago.

The Samaritans call themselves Shamerim, meaning guardians of the truth. They hold as sacred the five books of Moses but have never accepted as canon the Prophets or Writings, or the Talmud — the compendium of Jewish oral law.

Their Torah, written on parchment in the ancient Hebrew alphabet, contains some 6,000 variants from the Masoretic Hebrew Bible. Most of these are discrepancies over spelling or pronunciation. Some, however, reflect the bitter historical and religious struggle waged in antiquity between the Samaritans and the Jews.

For example, the Ten Commandments as they are known to Jews and Christian alike have been compressed into nine in the Samaritan version. A tenth commandment drawn up from passages in Deuteronomy 11 and 27 proclaims the sanctity of Mount Gerizim, the Mount of Blessing. The Samaritans observe only the biblical Holy Days: the New Year, Day of Atonement, Tabernacles (Sukkot), Pentecost (Shavuot) and Passover, the latter being their most important festival.

The community’s high priest traces his genealogy back to the biblical figure Uziel, son of Kohath, son of Levi. It was the Levites who assisted the Kohanim in their priestly duties in Solomon’s temple.

Until 1624, there had existed a chain of high priests descended from Eleazar, the son of Aaron and the nephew of Moses.

In addition to his official duties as final arbiter in matters of religion and as leader of religious ceremonies, Abdallah Wasef has encouraged the young to learn their historical and literary traditions from the community’s sages and has endeavoured to find matches for the unwed. More than half of Samaritans are under the age of 30.

In 722 B.C., 200 years after the split between Solomon’s sons Jeroboam and Rehoboam, the Kingdom of Israel was destroyed by the Assyrians. Many of the vanquished population were deported as slaves to Mesopotamia, or present-day Iraq. Vassal people living in what is now Syria at the border between Iran and Iraq were brought in their stead to settle the barren land.

A Samarian Torah scroll. Photo by Gil Zohar.

Jewish tradition maintains that the Samaritans are the descendants of these colonizers who adopted some Israelite rituals (II Kings 17:24-29), a charge adamantly denied by the Samaritans.

The enmity between the Jews and Samaritans continued for centuries. The Hebrew prophets continually upbraided the northerners for their sins. Isaiah delivered a tongue-lashing against “the drunkards of Ephraim” (Isaiah 28:1), and the name Jezebel, the wife of King Ahab, has become a synonym for impudence and licentiousness.

The parable of the good Samaritan in the Gospels (Luke 10:2-37) obliquely refers to the acrimonious relations between the rival faiths. Jesus uses Samaritans as a metaphor for despised yet helping people, like the good Christian.

In the Talmud, Samaritans are disparagingly called “Cutheans” after the Babylonian city of Kuthah, one of the places from which the Assyrians relocated settlers.

At the beginning of the Christian era, upwards of a million Samaritans were living in the hill country and plains of central Palestine, and Nablus had developed into a major city. The first-century Jewish historian Josephus recounted the ancient love story that led to the construction of the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim in 332 B.C.

According to Josephus, a Jerusalem high priest named Menashe flouted Jewish law by marrying a Samaritan woman named Nikaso. Menashe was given the choice of leaving his wife or the temple cult. Nikaso’s father Sanballat, leader of the Samaritans, promised to build him an exact replica of the Jerusalem temple and make him high priest there.

In 170 B.C., the Seleucid ruler Antiochus I converted the temple into a shrine to Zeus. Both the pagan sanctuary and the city below were razed by John Hyrcanus in 113 B.C. The zealous Hasmonean king also conquered Idumea to the south, the homeland of the biblical Edomites, whom he forcibly converted to Judaism.

This tradition of persecution was continued by the Christian Byzantines, who built the Church of Mary Theotokos atop the ruins starting in A.D. 484. Throughout the centuries, the Samaritan population gradually dwindled, decimated by the crushed revolts against Byzantine rule in 444 and 555 and forced conversions.

With the conquest of the Holy Land by Muslims in 637, the Samaritans became a pariah people restricted to their ghettos and compelled to wear distinctive dress.

By the time of the Crusades, they were reduced from a great nation to a scattered and broken sect — one segment in their ancient homeland, another in Damascus and a third spread thinly along the coastal towns between Jaffa and Egypt.

By the middle of the 19th century, all settlements other than Nablus had been abandoned and their remaining members concentrated in the enclave at the foot of Mount Gerizim.

In 1918, when the British army’s advance precipitated the collapse of the tottering Ottoman Empire toward the end of the World War I, the Samaritan population had been reduced to 146 souls. The ancient culture was on the brink of extinction.

In addition, the custom of endogamous marriage had led to dangerous inbreeding, resulting in a high percentage of genetic defects — including color blindness, congenital respiratory deficiency and deafness. Moreover, male births outnumbered females 2-to-1, resulting in an acute shortage of potential spouses.

The Samaritans were rescued from ultimate oblivion by Zionism and the beginning of large-scale Jewish immigration to Palestine in the early 1920s. At that time, some 54 Samaritans left the primitive conditions of the Nablus ghetto to live in Holon, a new Jewish settlement near the port city of Jaffa — predominantly Arab at the time — and the newly founded Jewish town of Tel Aviv.

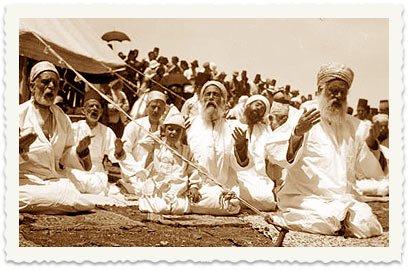

The Samaritan Passover celebration in 1934. Creative Commons photo.

Most of the settlers were members of two clans: the Tsedakah and Marhib. In 1924, one of these settlers, Yefet Tsedakah, met and married a “halutza” — a Zionist pioneer — who had recently immigrated from Russia.

Their union was the first between the lines of Israel and Judah since the time of King Solomon. A number of such marriages have taken place in the ensuing decades, all between Samaritan men and female Jews. There is no male conversion procedure.

Throughout the years of British rule, the enclave in Holon remained static, numbering between 40 and 50. Following the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, Israel’s War of Independence and Jordan’s annexation of Judea and Samaria — renamed the West Bank — the Samaritans were divided in two. Families left Nablus to join their kin in Holon, making the two communities roughly equal in number.

How Samaritans became divided, then united

The Samaritans of Holon were recognized as children of Israel under the Law of Return, Israel’s repatriation act, and became full-fledged citizens of the nascent Jewish state.

Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, Israel’s second president, took a personal interest in their integration. Due to his efforts, a self-contained neighborhood, Shikun ha-Shomronim, was built in Holon in 1954. Nine years later, a “kinshah,” or synagogue and community center, were added.

The Samaritans of Holon gradually adjusted to the ethos of a modern Westernized society. The younger generation has become progressively acculturated, though resistive to religious assimilation so far. In external appearance, Holon Samaritans are indistinguishable from their Jewish neighbors and serve together with them in Tzahal, the Israel Defense Forces.

The 1949 truce secured in Rhodes, which ending hostilities between Israel and its Arab neighbors, contained a provision guaranteeing Israeli Samaritans the right to visit their relatives in Nablus and to participate in the Passover pilgrimage to Mount Gerizim. However, the Jordanians honored this agreement mainly in the breach, claiming it would infringe on security.

For the next 18 years, the Passover celebration was the sole occasion when most of the community was united. The Paschal lamb sacrifice became an annual assembly for matchmaking. In consultation with the high priest, prospective couples decided which partner would join the other to live in Israel or Jordan.

During this period, the Holon community became progressively more established and prosperous, and the Nablus community more impoverished and persecuted.

With the Israeli victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, the two communities were free to meet all year long. A feeling of national renaissance took hold. Never faltering in their belief that they are God’s chosen people and that the day will come when providence will again favor them, the Samaritans interpreted the reunion of their divided community as a divine omen.

Israel’s Civil Administration has indeed proven to be a blessing. The Samaritan presence in Nablus dovetails with right-wing Israeli desires to settle the biblical heartland of Judea and Samaria, notwithstanding Israel’s 1996 withdrawal from the city of 130,000. That year, Nablus Samaritans were granted Israeli citizenship.

The settlement of Qiryat Luza was built on Mount Gerizim, strategically overlooking Nablus, an-Najah University and the Balata refugee camp — all hotbeds of Palestinian nationalism and scenes of rioting during the uprising.

Archaeological excavations were carried out for 18 years, beginning in 1982, and led by Yitzhak Magen — the Israeli Civil Administration’s chief archaeologist for the West Bank — as if to further strengthen the connection between past and present. In 2000, the Israel Antiquities Authority dedicated a 100-acre archaeological park comprising the Samaritan temple and other remains.

The 3,000-year-old rift between Jews and Samaritans has been healed. The Samaritans today may be seen as the pitiful remnant of a once-sovereign nation whose system of religious beliefs has been seemingly arrested in time, but they are also an illustration of how ethnic and religious conservatism can safeguard a minority group that would otherwise have vanished — almost without a trace.

Gil Zohar was born in Toronto, Canada, and moved to Jerusalem, Israel, in 1982. He is a journalist writing for The Jerusalem Post, Segula magazine, Religion Unplugged and other publications. He’s also a professional tour guide who likes to weave together the Holy Land’s multiple narratives. He may be reached at GilZohar@rogers.com.