The faith that made runner Jim Ryun forgive his Olympic rivals

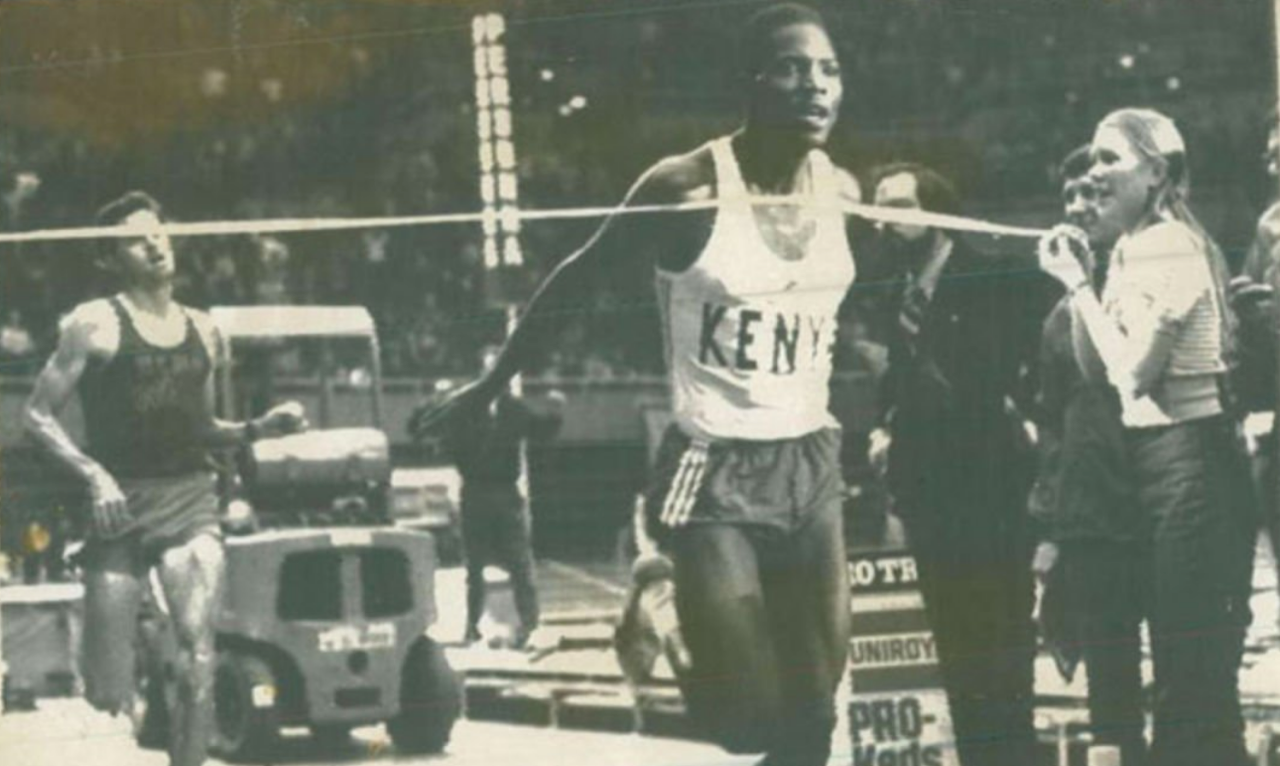

Kenya'a Ben Jipcho leaves world record holder Jim Ryun behind as he wins the mile during the sensational professional debut at Uniondale, New York, in this 1974 photo. Jipcho also won the two-mile event. Photo by Nation Media Group.

NAIROBI — Kenyan Olympic legend Ben Jipcho, 77, died in the Kenyan city of Eldoret on July 24. On the same day, thousands of kilometers away in Washington, D.C., another Olympic legend, Jim Ryun, received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in the White House.

The cruel irony of fate saw two distance running greats enter different chapters, in stark contrast.

Jipcho died a disturbed man, concerned that the Kenyan government neglected him as he sought financial support to tackle his hospital bills. He succumbed to multiple organ failure, a condition that could have been treated with proper medical care.

Meanwhile, Ryun, an American, was celebrating the highest civilian honor, given by U.S. President Donald Trump, for a stellar contribution to country, both on the track and off it. He also served 10 years in the U.S. House of Representatives for Kansas.

Perhaps what Jipcho and Ryun shared in common was the fact that they both never won a gold medal at the Olympics, both settling for silver in their golden careers.

However, Ryun was, for a while, bitter that it was Jipcho who denied him the chance to strike gold at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City.

The casket holding the remains of Kenya's athletics legend Ben Jipcho during his burial ceremony at his rural home in Kisawai village, Trans Nzoia County on July 31, 2020. Photo by Nation Media Group.

This after Jipcho had employed what was then considered illegal tactics by playing “rabbit” (setting the pace) for his captain Kipchoge Keino to coast to victory in the 1,500 meters final in Mexico.

At the time Ryun was untouchable, a red-hot favorite for the gold medal at the Estadio Olimpico Universatario. After all, just a few months earlier, he had shown Keino a clean pair of spikes at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum when shattering the world 1,500 meters, clocking three minutes, 33.1 seconds in the USA vs. Commonwealth match on July 8, 1967. And what’s more, despite the “thin” air of Mexico City (2,300 meters), Keino had entered three races at the 1968 Games — the 10,000, 5,000 and 1,500 meters — against doctors’ orders.

The final of the 1,500 meters on October 20 would be Keino’s sixth race inside eight days, meaning that a fresh Ryun was expected to win. At the time, Keino was battling gallbladder problems that saw him collapse in the infield with about two laps to go in the 10,000 meter final on (for him) an unlucky October 13 day of action, with compatriot Naftali Temu bagging Kenya’s first-ever Olympic gold medal, crossing the line in 29 minutes, 27.4 seconds to ward off a challenge from Ethiopia’s Mamo Wolde (29:28.0) and Tunisia’s Mohamed Gammoudi (29:34.2).

On October 17, Keino bounced back to dig in for silver in the 5,000 meter (14:05.2) behind Gammoudi (14:05.0) with Temu (14:06.4) taking bronze.

The Kenyan captain had used almost all his reserves, and no-one gave him a chance of upstaging Ryun, who had floored him in the semi-finals of the 1,500 meter race, with Jipcho grabbing the final qualification slot.

But what happened on the day of the final remains one of the Games’ talking points.

Warned by team doctors that if he ran another race he’d drop dead, Keino was left behind in the Games Village to recuperate.

“But I told our team officials not to remove me from the start list,” Keino recalled earlier this week. “I asked myself what would I tell the President (Jomo Kenyatta) if I returned home as team captain without a gold medal?”

He jumped onto the next bus which was caught up in traffic close by the stadium.

“Time was running out and I jumped off the bus and got to the warm up track 15 minutes to the race. We would be transported from the warm up track to the competition arena… I should have arrived earlier but I was stopped several times by policemen who told me I wasn’t supposed to be running through that area.”

And when the race started, Keino knew just what the game plan was. Team orders were in place, orchestrated by “Team Kenya” coaches who included the late Charles Mukora and British volunteer John Velzian.

“I told Jipcho to start off on a fast pace and to be wary especially of the American Ryun and German (Bodo) Tummler,” Keino said.

And at the starter’s gun, Jipcho blasted off like a man possessed, crossing the 400-meter mark in a blistering 55.98 seconds, well inside a sub four-minute schedule.

Germans Harold Norpoth and Bodo Tummler (European champion) sandwiched Keino in second and fourth with Ryun way back in eight with the Kenyan captain weighing his options on the outside of the pack, the 800-meter split: 1:55.31.

“Clearly this is team running for Kenya designed to produce the gold medal for Keino,” said BBC’s commentator David Coleman as he read the game plan. “The pace is suicidal, well inside world record pace. If this goes on, the world record will fall at altitude… the American has been taken for a ride, Keino coming up to the bell...”

And with 200 meters to go, it was game over.

“And Keino will never be caught… the Kenyan, beaten in the 5,000-meter for speed, shows the world record holder the way home,” Coleman said as the race ended. “Ryun completely misjudged this… the Kenyans have beaten him tactically out of sight!”

Keino’s winning time of 3:34.91 was a new Olympic record and the 20-meter winning gap the biggest to date in the history of the 1,500 meter final at the Olympic Games.

This infuriated Ryun who was up in arms against the Kenyan’s tactics as pace-making was considered illegal at the time.

Four years later at the Munich 1972 Games, Ryun was, once again, the favorite to win gold in the 1,500 meter, but with just over a lap to go in the fourth heat, and as he made his move, the world record holder was tripped and fell down, temporarily unconscious. He struggled to get up and finish the race in ninth place.

But his appeal for reinstatement fell through, and that marked the end of his Olympic dream.

Months later, a now born-again Christian, Ryun — who in his childhood days, had been dropped from his church baseball team and couldn’t make the junior high school basketball team — forgave the competitor who had tripped him in Munich.

“I realized my responsibility was to be faithful to God and to forgive that man, and ask God to give me a forgiving attitude,” he told JCTV in a 2011 interview.

Back to the baseball and basketball teams: Ryun never gave up even after being dropped, instead trying his hand in track and field, and always saying a prayer.

“These achievements we are celebrating began with a simple prayer after being cut from the church baseball team, junior high basketball team, and the junior — well, I never made the junior high track team,” Ryun recalled at the White House ceremony.

“I began ending each day with this simple prayer — and, by the way, I’ll throw it out there for you that if you’re looking for something, this would be a good way to start:

“Dear God, I’d like my life to amount to something. I believe you have a plan for my life. I’d appreciate your help in figuring it out. And if you could help me out and make a plan that would include sports of some kind, I’d really appreciate it. Thank you, and goodnight.”

“God did indeed show up in a huge way, answering my simple, heartfelt prayer,” Ryun said. “I finally made my first athletic team, the Wichita East cross-country team, my sophomore year in high school.”

He only attended East High School (he lived closer to another school) because he didn’t have plans to go to college but instead, a vo-tech school to be a draftsmen and follow his father and brother to work at Boeing. At East High School, a former Marine, Bob Timmons, coached Ryun into shape.

Meanwhile, Ryun wasn’t really interested in politics after his stellar running career, until 1996, the same year he was elected Member of the U.S. House of Representatives in which he served the Second Congressional District of Kansas for 10 years.

And, by coincidence, he was awarded the highest civilian honor in the U.S. — the Presidential Medal of Freedom— the very same day that his nemesis of 1968 Jipcho died in Eldoret.

“It is good to hear from you though with sad news about Ben’s passing,” Ryun, 73, responded when I reached out to him for a reflection on his competition days with Jipcho. “Ben was a remarkable athlete with great talents.”

Jipcho, along with Keino became the first Kenyan athletes to turn professional in the 70s, then running on the International Track Association circuit which is, perhaps, comparable to the modern Diamond League.

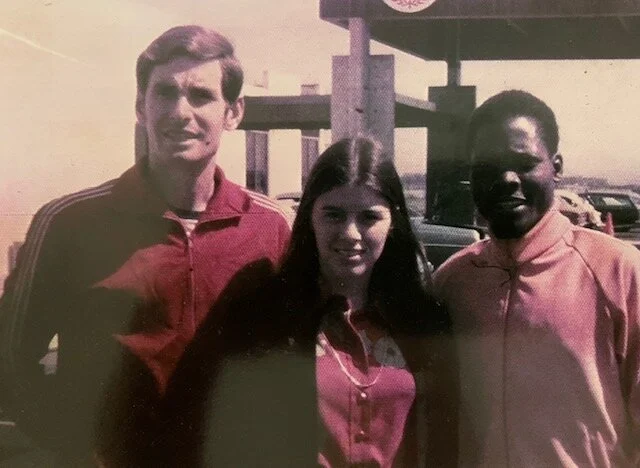

U.S. athletics legend and former world 1,500m record holder Jim Ryun (left) with photographer Paige Powell (center) and Kenyan track legend Ben Jipcho in Portland, Oregon, in 1974. Photo courtesy of the Ryun family.

Ryun recalls that it was during one of their meetings on the circuit in 1974 that Jipcho reached out to him and apologized for the Kenyan ruse at the 1968 Olympics.

“During the International Track Association season of competition, Ben came to me and asked for my forgiveness in illegally rabbiting the 1,500-meter final at the Mexico City 1968 Olympics,” Ryun said in our conversation.

He expressed his disappointment for doing what he did because he knew it should have been a race between Kip and me.

“I readily forgave him having just become a Christian on May 18, 1972,” Ryun said.

The American legend explained that Jipcho had been instructed by Kenyan officials to burn him (Ryun) out.

“Ben had been told by the Kenyan track and field authorities that he would rabbit (set a blistering pace) in the race to ensure a Keino win.

“They promised Ben the next Olympics would be his,” Ryun said. “His coming to me (to apologize) was completely unsolicited and was a display of great character. To this day, I admire Ben for his character probably even more so than his running talent. It is a man’s character that lives on long after our running legs give out and it is character that is passed on to the next generation.”

Then Ryun and his wife Anne sent their condolences to Jipcho’s family along with their prayers for Christ’s peace “that passes our own understanding.”

Ryun signed off his email with the Bible verses John 3:3-8: (KJV):

“Jesus answered and said unto him, Verily, verily, I say unto thee, except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God.

“Nicodemus saith unto him, How can a man be born when he is old? can he enter the second time into his mother's womb, and be born?

“Jesus answered, Verily, verily, I say unto thee, Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God.

“That which is born of the flesh is flesh; and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit.

“Marvel not that I said unto thee, Ye must be born again.

“The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit.”

Kenya’s coach at the 1968 Olympics, John Velzian, is currently 92, living alone in Nairobi.

I reached out to him for comment, but with his advanced age, and failing memory, he couldn’t clearly recollect the events of Mexico City. In fact, he hadn’t known of Jipcho’s demise.

“We’ve had good times with Jipcho,” he responded when I broke the news. “It’s difficult these days for me to speak to any of my athletes… But I’ve had a great life and they have kept me safe and I have kept them safe.”

Velzian says since his son moved to New Zealand and his daughter to London, he’s been living alone.

U.S. President Donald Trump applauds after awarding the Presidential Medal of Freedom to former U.S. Representative Jim Ryun (left) in the Blue Room of the White House on July 24, 2020. Ryun, a three-time Olympian, won a silver medal in the 1,500m at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, and was the first high school athlete to run a mile in under four minutes. Photo courtesy of the Ryun family.

Meanwhile, as he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in the Blue Room of the White House last Friday, Ryun fought back tears as he probably recalled the highs and lows of his stellar running career, and his contribution to U.S. track and field.

President Trump highlighted Ryun’s achievements, talking about his journey that started with a prayer:

“After being cut from his church baseball team and junior high school basketball team he asked God for guidance. Jim wanted to know God’s plan for him, and he only had one request: that it was something to do with sports. That prayer was answered when Jim joined the high school track. He joined it and had no experience whatsoever. As he said, he didn’t really know what he was doing, and he didn’t know what he was doing there. When ESPN ranked the greatest high school athletes of all time, all sports, they listed Jim Ryun as number one. That’s not bad for a guy who couldn’t make his baseball team, right? That’s really — that’s really an amazing achievement. That’s incredible. In 1975, he founded the Jim Ryun Running Camps. For the past 45 years, Jim has helped teach thousands of young people to reach their fullest and best athletic potential. He has been a dedicated mentor to campers and shared in the critical importance of a Christian faith. He’s very devoted to Christianity. In 1996, Jim was elected to the House of Representatives, and he went on to serve five terms in Congress. He was a principled, committed, very tough and beloved lawmaker. That’s what they said: He was tough and yet beloved. That’s a rare combination. He’s a giant of American athletics, a dedicated public servant, and a man of charity, generosity, and faith. He’s a great man, actually. Jim, thank you for your unfailing devotion to our country, and congratulations on a lifetime of incredible success, not only athletically — that was obviously a big deal — but what you’ve done in life and even with you family has been just incredible. So I’d like to congratulate you very much.”

Indeed, July 24, 2020, will remain a most memorable date for Congressman Ryun and family.

Elias Makori (elias.makori@ymail.com) is the Sports Editor at the Nation Media Group in Kenya and a fellow of The Media Project. A version of this story was published by the ‘Daily Nation.’